New Diversities • Article 22, No. 1, 2020

Enabling Diversity Practices in Istanbul

by Semahat Ceren Say and Başak Demireş Özkul (Istanbul Technical University)

To cite this article: Say, S. C., & Özkul, B. D. (2020). Enabling Diversity Practices in Istanbul. New Diversities, Article 22(1). https://doi.org/10.58002/bm6m-j107

Abstract: It is important that contemporary global cities provide opportunities for increasingly diverse communities to thrive. These cities, and particularly their local governments, have to adapt and reassess their provision of services for changing expectations and requirements, as well as bear the responsibility of redefining their role for both new and established residents. This paper examines the policies and initiatives that Istanbul’s local municipalities have adopted in districts that have historically served diverse communities. The paper demonstrates that inclusive national regulations are required for the adoption of inclusive planning, governance and service provision in local administrative and economic centers. These efforts could be supported by international recognition of diversity policies through transnational policy networks.

Keywords: diversity, inclusive planning, local governance, Istanbul

Introduction

Diversity has become an important phenomenon in metropolitan cities. Due to the rise of international migration flows, urban centers have become areas of confluence with increasingly diverse residents and a growing number of newcomers. Globalization, conflicts and severe living conditions in various countries have fostered these flows (U.N. Habitat 2008). Such dynamics add an extra burden to local municipalities whose mission is to respond to the needs of increasingly diverse communities. These pressures are more acutely felt in municipalities that form the core of global metropolitan cities, as they accommodate primary functions such as administration, tourism, business and entertainment that are frequented by both established residents and newcomers.

Due to contemporary conditions, which necessitate a broader analysis of diversity, this study contributes to diversity literature in Istanbul by focusing on policies that address social diversity such as age, gender, ethnicity, culture, etc. The municipalities’ approach to social integration for all its residents is better understood and assessed from this perspective. Our findings demonstrate that migrants from different parts of Turkey as well as from other countries are regarded as diverse groups, which indicate notions of super diversity and hyper-diversity. Istanbul has hosted various kinds of diversities throughout its long history (minorities, internal migrants from small towns, etc.). This work offers insights to debates on equality and on the value of the concept of ‘public benefit’ (kamu yararı) within policy making and planning in Turkey. In this regard, this paper aims to explain the role of local municipalities in addressing diversity in Istanbul and reflect the municipalities’ involvement with EU-related municipal networks and projects that focus on the issue of diversity. The article principally addresses two questions: how do local municipalities perceive and interpret diversity? And, how do international diversity policy networks influence practices in three core municipalities of Istanbul? In addition, we will discuss the efficacy of local policy on accommodating diversity and the relationship between planning and diversity.

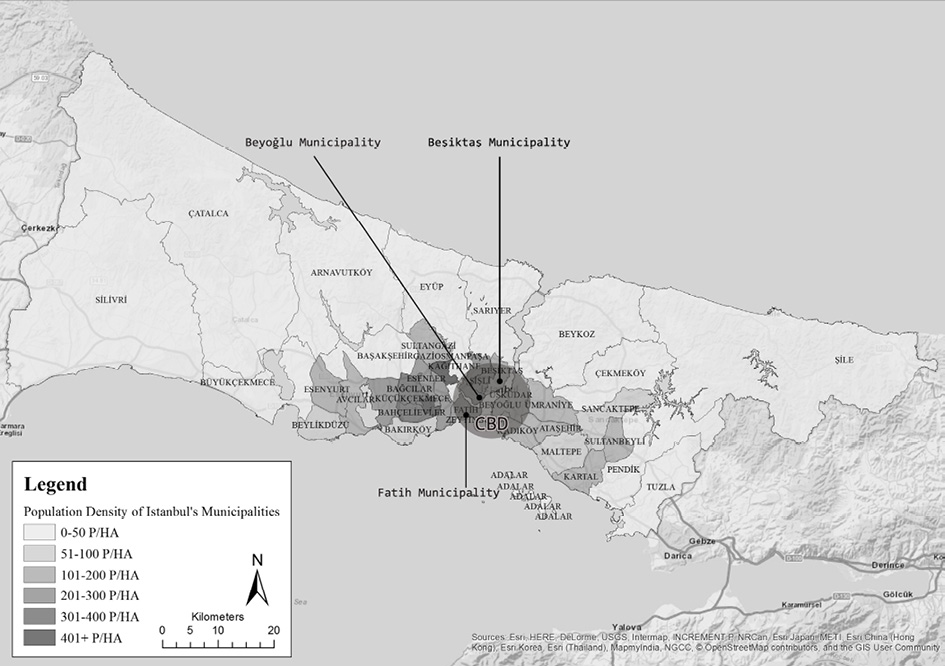

This article is based on a research project comprised of three case studies in the central area of Istanbul. In order to compare each municipality’s definition of diversity and its inclusionary practices, we chose to focus on the following three districts: Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş and Fatih. Each of the three municipalities has different constituents and occupies a central part of Istanbul. Furthermore, the study investigates the local municipalities’ membership to international networks by comparing two EU-supported local governance network member municipalities (Beşiktaş, Beyoğlu) with a nonmember municipality (Fatih). Although there are a number of networks within the UN and EU that have been instrumental in creating and spreading diversity-related practices, this study examines UCLG-MEWA, Eurocities and ICC, which have memberships in Turkey, in order to illustrate the key actors and the main elements in creating successful diversity practices.

In the study, the perception of diversity by municipal administrators and officials and inclusionary practices of each municipality were evaluated by examining each municipality’s strategic development plan and related activity and performance reports. To analyze the practices of the municipalities, we conducted in-depth interviews with various planning and service directorates in these municipalities.

To better understand global cities, it is critical to examine the notion of urban diversity. Due to shifts in capital and changing modes of production, globalization has triggered the flow of people in today’s capitalist system (Koenig and de Guchteneire 2007). Urban diversity can be defined through physical (density, mix-use, etc.), social (ethnic, socio-cultural, socio-demographic, socio-economic diversity) and economic parameters (economic growth, creativity, innovation). In this study, we focus on social diversity in three core districts of Istanbul, Turkey.

As stated by McDowell (1999), cities are the places where intersections of global movements occur. In this sense, global cities gain importance, since the global economy depends on these cities (Sassen 1994). Within large global cities such as Istanbul, the existing inhabitants have differing social characteristics (age, gender, financial situation, dis/ability, etc.) that create a diverse structure; however, the addition of people from different nations and ethnicities brings new and already-existing divisions amongst inhabitants to the fore and leads to a higher potential for conflict among various social groups. In cities that have received larger numbers of migrants, such as Istanbul, changes in social demographics necessitated the creation of inclusive policies. In this sense, policy approaches to diversity evolved from assimilation to multiculturalism in Europe. Assimilation can be defined as an acceptance of the majority group’s cultural identity (Berry 2011), whereas multiculturalism offers the recognition and participation of cultural minorities in society (Faist 2009). Today, multiculturalism has shifted toward interculturalism, which focuses on the importance of cultural dialogue and encourages difference while also emphasizing the importance of common interests and mutual understanding (Amin 2002; Stevenson 2013). Global cities’ dynamic sociodemographic structure allows us to follow the trajectory of diversity policies.

The efforts of intergovernmental organizations such as the European Union (EU) and the United Nations (UN) and its subsidiary organizations have had a significant impact on the formation of policies on diversity and inclusion, particularly regarding anti-discrimination and equality principles. The combination of these efforts with international agreements has created a “human-rights revolution”, which demonstrates the new policies’ influence and their increased emphasis on culture, especially in Europe (Kymlicka 2012). International agreements and commitments in recent decades have led to the creation of documents such as ‘Our Creative Diversity Report’(1996), ‘Declaration on Cultural Diversity’ (2000), ‘Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions’ (2005), and the ‘White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue’ (2008), which all underline the importance of policies to accommodate diversity, with an emphasis on cultural diversity. The idea of interculturality and subsequent diversity policies emerged to counter criticism on multiculturalism and assimilation (Schiller 2016). Convergence policies in Europe started to emerge with the notion of interculturalism, with particular influence on shared values. Interculturalism also brought about local practices in accommodating diversity. Emphasizing interculturalism, Amin (2002, 2013) focuses on the importance of negotiating difference in everyday interactions. In this regard, he stresses the importance of shared activities in communal spaces, which can occur in workplaces or through community organizations. Since spatial identities are composed of interactions from global to local (Massey, 2004), multi-tiered models of governance emerged for pioneering diversity (Sandercock 2003). Diversity policies and practices can be influenced by national legislation, funds or policies, or through exchanges between cities. However, due to decentralization policies, especially after 1990s, the influence of national and regional laws have had a decreasing effect on local policies (Schiller 2016). Therefore, local municipalities in European cities have come to the forefront in putting diversity policies into practice.

Policy and ideas are dispersed globally and cities act autonomously in policy development and implementation (Faist and Ette 2007). Therefore, international municipal networks have taken shape to promote policy exchanges and knowledge-sharing of best practices, as well as to enable the exchange of ideas among local municipalities. These networks are important, as they create an environment for cities to share their ideas, experiences, knowledge. Joint actions allow municipalities to adopt common policies and actions. Such alliances also have the potential to influence supranational and international policies (Duxbury and Jeannotte 2013). These networks increase the status of these cities and they become more like “supranational authorities,” creating an opportunity for cities to connect with these “authorities” and with other cities to create partnerships (Payre 2010). These networks can become key actors for creating multilevel governance of diversity by emphasizing “interdependence, consensus, and cooperation” instead of “hierarchy, imposition and power” (Caponio 2018). Sometimes these international municipal networks have very little effect on cities, however, as the policies triggered by these networks are not implemented due to the indifference of the administrative bodies (Downing 2015). In this regard, policy convergence could be a solution to make these networks more effective, by preventing attempts to undermine their role by local actors due to the lack of consensus and coordination (Caponio 2018). Policy convergence would be achieved through the initiative of national governments in promoting diversity in supranational institutions such as the EU.

The terms super-diversity and hyper-diversity have been used to reflect recent changes in world demographics. As international migration flows increased in the 21st century, it was insufficient to simply focus on race and ethnicity, as there can be differences between migrants coming from the same country of origin. This realization brought multiple identifications and differentiations among these migrants that created the term super-diversity (Vertovec 2007). In addition to super-diversity, the term hyper-diversity also emphasizes that differences can occur both within and among local people and newcomers (Tasan-Kok et al 2014). Kraus (2012) has mentioned the difficulty of defining cultural identity as a specific category, even when talking about a single nation. These multi-faceted diverse identities could be better defined by using super-diversity and hyper-diversity. In this regard, the EU’s latest perspective on diversity could overlap with the understanding of interculturalism which focuses on the importance of dialogue in solving conflicts in these super-diverse environments. As mentioned by Abdou and Geddes (2017), the EU’s intercultural turn focuses on the economic benefits of diversity and its potential to solve conflicts. Moreover, the positive assets of diversity can contribute to the provision of social cohesion and local identity if a rights-based approach is adopted in policy-making.

In Turkey, the ongoing migration from neighboring countries has been studied within the fields of sociology, geography, planning, etc. The number of studies has increased in the aftermath of migration from Syria after 2011. These studies focus on several topics such as changing migration trends and demographics, problems related to integration/adaptation and policies, and strategies implemented by the national government (Erdoğan and Kaya 2015, AFAD 2013, Içduygu and Aksel 2013, Içduygu 2015, Kirisci 2014, Erdoğan 2015). There have also been studies focusing on the role of local actors (municipalities, non-profit organizations) in responding to the newcomers (Erdoğan 2017, Woods and Kayalı 2017, Koca et al. 2017, Danış and Nazlı 2019). These studies show different approaches of municipalities toward Syrian migrants. There have also been some studies that have focused on migration from a diversity perspective. The multinational “Divercities” study (Eraydın et al. 2014, Yersen 2015, Eraydın et al. 2017) examines the governance of urban diversity through the lens of various actors (central government, municipalities, non-governmental agencies)in Istanbul by focusing on Beyoğlu municipality. Furthermore, Biehl (2015) examined the diversification of local space by focusing on the Kumkapı neighbourhood in Istanbul through the lens of super-diversity.

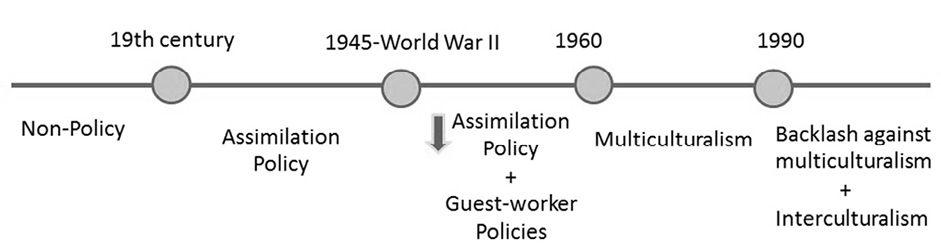

Diversity as a Positive Asset for Cities

As diversity has increased through migrant flows, various policy approaches have been developed to address it (Figure 1). In the 19th and 20th centuries, assimilation policies were implemented by nation states such as Western European countries like Germany or France since newcomers were seen as a threat to the host country. After World War II, although assimilationist policies were still ongoing, their influence started to decrease. The anti-nazism sentiment and an emphasis on equality created the environment for a reevaluation of human rights (Kymlicka 2012). The UN encouraged minority identities by accepting anti-discrimination and equality principles (Koenig and de Guchteneire 2007). Multicultural policies in Western Europe increased particularly after the 1960s and the human-rights revolution. International agreements were signed for promoting anti-discrimination and equality such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (Yersen 2015; Koenig and Guchteneire 2007). Multicultural policies were supported and adopted by several nations until the mid-1990s. However, backlash toward multiculturalism shifted diversity approaches towards “civic integration,” “social cohesion,” “common values,” and “shared citizenship” (Kymlicka 2012). In this regard, the EU sought to implement convergence policies and the European Council accepted the “Common Basic Principles of Immigrant Integration Policy” in 2004 to create a path and context for integration policy (Joppke 2007). These approaches were also supported by interculturalism which emphasized the importance of shared values in diversity policies.

Diversity in cities has been portrayed by academics within two opposing frameworks: its benefits to socio-economic vitality, economic development and social equity, and its detrimental effects on social cohesion and social capital. Diversity has been shown to increase economic vitality, economic growth, innovation, creativity, economic productivity and decrease unemployment (Jacobs 1961; Talen 2006; Florida 2012; Granovetter 1983; Putnam 2007). From this perspective, diversity has been beneficial to the economy by increasing economic growth and productivity (Landry and Wood 2012; Talen 2006; Putnam 2007). Talen (2006) emphasizes the importance of diversity on equality, as investments to diverse enclaves would be much higher compared to segregated low-income enclaves. According to Beatley and Manning (1997), stimulating diversity can have a positive effect on urban sustainability by preventing segregation and enabling equal access to basic services and facilities. However, some contradictions have arisen in terms of the relationship between social cohesion and diversity. Diversity has the potential to lead to conflict (Tasan-Kok et al 2014) and decrease social capital (Putnam 2007). In order to overcome these potential outcomes, it is necessary to focus on local policies to decrease conflict (Tasan-Kok et al 2014), promote inclusivity and solidarity (Putnam 2007) and provide equal access to basic services and facilities (Beatley and Manning 1997). This process could be accelerated if the benefits of diversity were perceived by the communities in question.

Local policies can promote the beneficial effects of diversity and minimize short-term deficiencies. Policies and practices that promote diversity and inclusion can increase the well-being of local communities and strengthen the social fabric of the city. Furthermore, the creation of public spaces, which are the primary areas where encounters take place, and the establishment of the idea of a common public interest, require inclusive planning. However, ethnic diversity and population mobility alongside other social, political and economic barriers have created constraints in creating more inclusive cities (CLG 2010). Several models have been suggested to solve the conflicts that may arise due to diversity and at the same time create inclusive public spaces. Young (1990), Healey (1997), Sandercock (2000) and Fainstein (2005) suggest the importance of interaction to solve injustices in society through mediation, collaborative and communicative planning and dialogue. There is also a debate between equality and diversity because interactions among different groups, especially immigrants and minorities, are fragile; here, equality is a concern. While some scholars state that diversity and equality cannot be separated from each other, others state that equality and diversity cannot occur at the same time. As emphasized by Reeves (2004) and Fainstein (2005), by ensuring equal opportunities, diversity can increase power and reduce the unequal competitiveness among different social groups. On the contrary, McDowell (1999) and Fraser (1990) claim that since not everyone has equal access to public space, the citizenship idea that is derived from equality actually creates exclusions and segregation in public space. Young (1990) also claims that equality can only exist in an ideal community and not in a diverse community. While some scholars claim that equality addresses issues of access to resources in cities, others cite the importance of addressing diversity separately from equality in order to overcome differences in power.

Local municipalities stand out as the primary responsible institution in designing, planning and regulating inclusive public and community spaces and providing services to a diverse range of local inhabitants. Local municipalities have countered exclusionary practices by identifying best-practices, articulating problems that rise from exclusion, and by raising the general public’s awareness. Although these practices have had some effect on decreasing exclusion, examples from the UK suggest that local interventions were more successful when social and physical renewal was accompanied by neighborhood management, resident involvement, local leadership and partnership, the availability of funding, and supportive national policies (CLG 2010).

International organizations such as the UN and the EU have also contributed significantly to a positive reception of diversity, either through international agreements or through the creation of various institutions and networks that have allowed member states to come together to discuss and further the ideas that have been established in these agreements. Furthermore, the programs such as Inticities, Dive, Mixities and ImpleMentoring created by these organizations have provided an opportunity for policies to be put into practice and to be evaluated. This has created an exchange of best-practices amongst participating authorities at various level of governance1.

United Cities and Local Government (UCLG) was established in the UN in 2004, which gathered city and municipal networks under one umbrella and spearheaded the creation of an international municipal movement (UCLG-MEWA 2017). The main elements of successful diversity practices in these networks and organizations include: agenda and charters that spell out a commitment to diversity; enabling mutual learning amongst partners and transferring ideas through peer review and mentorship programs; creating documentation related to anti-discrimination and integration; arranging thematic events and study visits and establishing thematic networks. The networks and organizations set up by the international organizations have provided benchmarks for successful projects in member cities and promoted diversity policies.

Europe is one of the major continents affected by international migration. Major policies related to diversity, such as international municipal networks, have been established under the auspices of the EU. The UN and the EU have supported several networks and organizations that encourage diversity, such as UCLG (United Cities and Local Governments), Eurocities, ICC (Intercultural Cities Program), URBACT, MPG (Migration Policy Group). These groups and programs have been instrumental in creating and disseminating practices related to diversity. Although Turkey is not a member of the EU, it has been an important country within such networks. The increase of migration from Syria after 2011 particularly strengthened the collaboration between the EU and Turkey as they partnered to provide solutions for these flows; the EU-Turkey refugee agreement was signed in 2016. Among the Turkish cities that participate within EU networks, Istanbul has the highest level of diversity due to its history, location and size.

Municipalities in Turkey have memberships in international and EU networks (Table 1). For instance, the Middle East and West Asia Section (UCLG-MEWA) is one of UCLG’s nine organizations and its general secretariat is located in Istanbul. The network created agendas and charters such as the ‘Agenda 21 for Culture’, the ‘Global Charter Agenda for Human Rights in the City’ and the ‘European Charter for Human Rights in the City’ for creating inclusive cities. Eurocities, which was developed by European municipalities and supported by EU, has memberships in Turkish cities such as Istanbul, Konya, Izmir and Gaziantep. Also, various district municipalities in Istanbul such as Beşiktaş, Beylikdüzü, Beyoğlu, Kadıköy, etc. have associated partnerships with this network. This network also created an “Integrating Cities Charter” and also arranged peer-review (Inticities, Dive, Mixities) and mentorship programs (ImpleMentoring) that contribute to accommodating diversity in cities. Finally, ICC which was developed by the Council of Europe and includes the municipalities of Osmangazi in the province of Bursa and Kepez in the province of Antalya, contributed to the idea of diversity by creating thematic events and visits as well as strategies for intercultural governance and citizenship. Several local municipalities in Turkey are part of networks that promote diversity at the local level.

|

Network/ Organization |

Key Actors |

Main Elements of Successful Diversity Practices |

Membership Situation of Turkey |

|

UCLG UCLG-MEWA |

UN |

*Agenda 21 for Culture *Global Charter-Agenda for Human Rights in the City *European Charter for Human Rights in the City |

UCLG-MEWA’s general secretariat is in Istanbul |

|

Eurocities |

EU local governments |

* peer-review and mentorship programmes (INTI-Cities, DIVE, MIXITIES, ImpleMentoring) *Integrating Cities Charter |

* Istanbul and several city municipalities have associated membership (Gaziantep, İzmir, Konya) *several local municipalities in Istanbul and also in other cities have associated partnership (Beşiktaş, Beylikdüzü, Beyoğlu, Kadıköy,etc.) |

|

ICC |

developed by Council of Europe |

*thematic events and study visits *developing strategies on intercultural governance and citizenship |

*Turkey- member state *Osmangazi/Bursa, Kepez/Antalya-member city |

Table 1. EU and UN supported organizations where Turkey is represented

Turkey, a country at the crossroads of Asia and Europe, is located on the main migration route from Middle Eastern countries to Europe. In this sense, Turkey’s location has special importance for the EU due to its role as a buffer zone. Turkey has housed diverse communities since the Ottoman Empire and still continues to be a diverse country due the large migration flows from its neighbor countries in recent decades. With the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923, diversity started to decrease as a consequence of the nation state ideal. Although democracy brought individual representation, it also caused fear of international intervention; in order to protect the unity of the newly established country, the representation of diverse social groups was limited. Furthermore, these social groups started to decrease in number with serious incidents such as the population exchanges between Turks and Greek in 1923, Thrace riots in 1934, Property Tax levies on minorities in 1942, Istanbul riots (6-7 September) in 1955 and the Cyprus Military Operation in 1974. After 1980, the diversity in Turkey increased again due to the internal migration from southeastern Turkey to the big cities, as well as international migration from neighboring countries due to political instabilities of these countries— especially from Syria after 2011.

Turkey’s definition and approach to diversity in terms of laws and regulations generally developed to address changing socio-demographics, which was also reflected in local practices. That said, there have been some measures to add inclusive clauses within the regulations in the last decades. Although there are no national anti-discrimination laws or institutions that are responsible for discrimination in Turkey (Kurban 2016), diverse groups (children, women, elderly, disabled people, refugees) fall under social welfare regulations within the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Family and Social Policies. In addition, the notion of ‘public benefit,’ which places the communities’ benefits before any individual’s, provides guidance for municipalities in creating policies in favor of communities. In the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey under the “social and economic rights and duties” section, the public benefit (kamu yararı) notion was described for coastal areas, land ownership, agriculture and livestock, expropriation, nationalization and privatization. Based on the notion of public benefit within the constitution, the Law on Public Improvement (İmar Kanunu) has bound municipalities to create policies and city planning initiatives in compliance with its definitions.

Furthermore, in 2013 the Law on Foreigners and International Protection (Law 6584) was passed to regulate the admission and protection of foreigners. Recent migration from Syria created an impasse because, according to the “Geneva Convention,” only migrants from European countries could be accepted as refugees in Turkey. The main agreement between Turkey and the EU was signed in 2016 to prevent further migration from Turkey to Europe.

The decentralization trend in the EU also had effects on Turkey. As part of the ascension process, local government reforms after the year 2000 [and Law 5216 on Metropolitan Municipalities (2004) and the Municipality Law 5393 (2005)] made the local governments more autonomous and increased public participation in local governance (Koçak and Ekşi 2010). The reforms included the creation of more inclusive and open public spaces by creating civic councils, accepting all inhabitants as fellow-citizens2 (Fellow-citizen Law/ Hemşehrilik Kanunu) and requiring strategic development plans in municipalities. Diversity-related strategies were developed, as well, through regional or city-level strategic plans. For instance, Istanbul Development Agency’s (ISTKA) Regional Plan (2014-2023) and Istanbul Metropolitan Municipalities Strategic Plan (2015) have emphasized inclusive society and inclusive urban transformation, participation, and enhancement of services for disadvantaged groups.

Local Approaches to Diversity in Istanbul; Beşiktaş, Beyoğlu and Fatih Municipalities

Due to its location and history as a global city, Istanbul is strategically important in creating practices that promote diversity. Firstly, its location creates connections with Balkans, Central Asia and Western Europe and its culture and commerce shaped the city as a global city (Burdett 2009). Istanbul’s situation is important, as it has a diverse background which dates back to the Ottoman Empire. It has hosted residents and minorities such as Greek, Armenian, Jewish, etc. within its borders, as it was the center of the Ottoman Empire:

“Such a cosmopolitan diversity, urban diversity is frequently found in developed countries and particularly in countries with an imperial history and a colonial past.” (Fatih Municipality, Directorate of Culture and Social Welfare Affairs, 12 March 2018)

Istanbul is still important in terms of diversity, although the number of residents from minority backgrounds has decreased; however, in recent decades the city has received a large number of migrants. According to statistics in 2015, 55% of the people that lived in Istanbul were not born in Istanbul and the city also hosted 17% of international migrants between 2010-2015 (Erdoğan 2017). Furthermore, Istanbul had the highest number of Syrian migrants among the cities in Turkey in 2016, which corresponded to 15-20% of the total population of Syrians (Erdoğan 2017). This study focuses on the central area of Istanbul, as delivery of resources and services in this region is higher because some of the services are concentrated in the center and the transportation network allows more people to access these services when compared to the peripheries. In addition, central areas do not just serve residents but also accommodate various visitors in daily life. For these reasons diversity practices in these areas become much more significant.

We chose three district municipalities as the case municipalities because district municipalities represent the local government and are directly elected by their local constituents. Also, these district municipalities have direct connections with local residents, unlike the Metropolitan Municipality, which is concerned with the welfare of the metropolitan city and is focused on larger system issues compared to district municipalities. The Beşiktaş and Beyoğlu municipalities were chosen due to their membership to the EU-based municipal network “Eurocities” and also due to their diverse demographics. The third municipality, Fatih, was selected to compare the two former municipalities with a municipality that has a large number of migrants and is not part of the network. Fatih is one of the oldest districts in Istanbul and, like Beyoğlu, has accommodated minority groups throughout history. Furthermore, it is fourth in terms of the number and proportion of Syrian migrants in Istanbul. Combined Beşiktaş, Beyoğlu and Fatih districts housed more than 850,000 Syrian migrants in 2016 (Beyoğlu ranked 19th and Beşiktaş ranked 37th among 39 municipalities in Istanbul) (Erdoğan 2017). Fatih also has the largest population [Beyoğlu (236.606), Fatih (433.873), Beşiktaş (185.447)] (Erdoğan 2017). All three municipalities are members of the UCLG-MEWA network and share borders, so they face common problems as well as have the potential to collaborate on policy and implementation, although there is political rivalry between municipalities: The Beyoğlu and Fatih municipalities are members of the governing party (AKP), while Beşiktaş municipality is held by the opponent party (CHP) municipality. Also, these municipalities can be considered pioneer municipalities, because the Metropolitan Municipality and the governorship is located in the Fatih district and has been the center of the city throughout the decades. On the other hand, Beyoğlu is also one of the most frequented places in Istanbul, since most leisure and entertainment activities take place in this district. It plays a special role in Istanbul because it has housed the highest percentage of minorities throughout its history. Also, Beyoğlu and Fatih have been pioneers in terms of urban renewal activities with controversial results (Unsal, 2015; Uysal and Korostoff 2015; Schoon 2014). The Beşiktaş district is also an attractive place due to its history and its various service units.

This study analyzed the socio-cultural and ethnic diversity as well as socio-economic and socio-demographic diversity and relevant inclusionary practices through document analysis of strategic development plans, activity and performance reports. After examining the documentation, we investigated the perception of diversity and related actions taken by the municipalities to gain broader knowledge and understand implementation. We did so by interviewing various directorates (planning professional and administrators, social affairs professional and administrators and foreign affairs professionals) in each municipality. We conducted eleven semi-structured interviews with various planning and service directorates in each municipality and UCLG-MEWA in 2018 (Say, 2018). The in-depth interview comprised questions about the description and perception of diversity, services for diverse groups, national and international cooperation, legal framework and planning. The interviews were conducted in Turkish and translated to English for publication. The results were evaluated through benchmarks from Eurocities peer-review programs INTI-Cities, DIVE, MIXITIES and mentorship programme ImpleMentoring. In order to select which benchmarks to use, we evaluated each one based on the activities and services that the municipality offered and focused on those that corresponded with local practices in Istanbul. In this study, the evaluation benchmark headings were determined as: perception of diversity; managing diversity in public administration and service provision; and governance and participation.

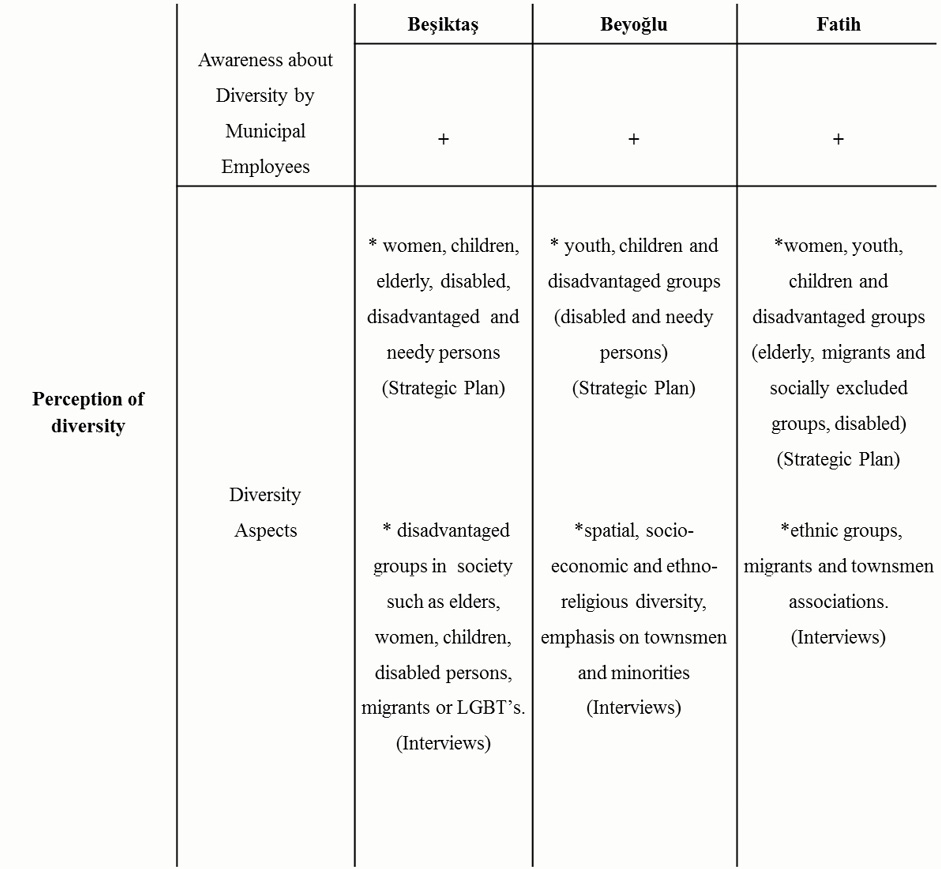

In all three municipalities, Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş and Fatih, administrators were aware of the meaning and importance of diversity (çeşitlilik) but sometimes found it hard to define. However, when the strategic development plans were analyzed, diversity was not mentioned directly. Furthermore, in Beyoğlu Municipality’s strategic plans the cosmopolitan structure of Beyoğlu was pointed out as a weakness even though internal stakeholders saw it as a strength (Beyoğlu Municipality 2015). In Fatih Municipality the recent wave of migration was seen as a threat for the district because it was perceived as an obstacle for the formation of an urban identity (Fatih Municipality 2015). However, these pronouncements do not signify that these municipalities were not addressing the needs of their diverse communities. Each municipality had identified ‘disadvantaged groups’. For instance, Beşiktaş Municipality mentioned lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) as a group to reach out to. Beşiktaş and Beyoğlu Municipalities on the other hand used fellow-citizen associations (hemşehri dernekleri) to reach disadvantaged communities in their districts (Table 2).

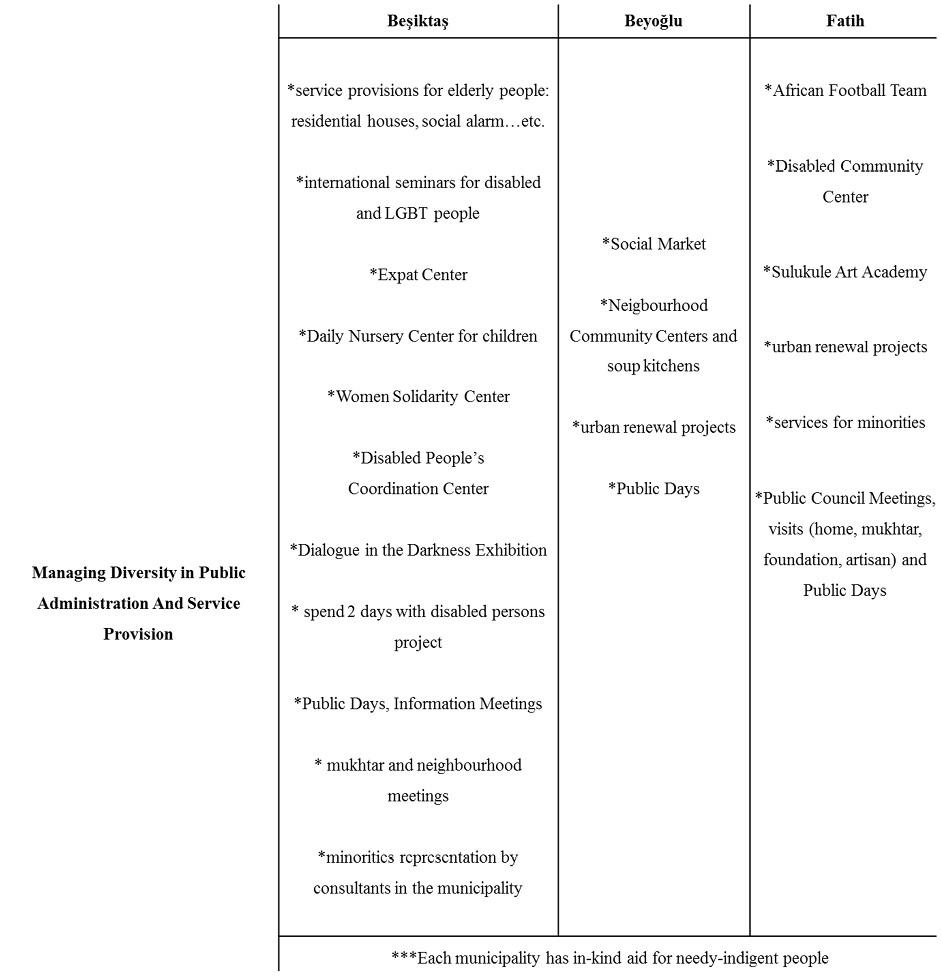

Each municipality identified a particular group for which they would provide public service (see Table 3). For instance, Beşiktaş Municipality focused on services for the elderly (residential houses, social alarm), people with disabilities (Dialogue in the Darkness Exhibition, spend 2 days with disabled people project, seminars of disabled) and other disadvantaged groups (Daily Nursery Center, Woman Solidarity Center, seminars for LGBT). The Beyoğlu municipality focused their attention to providing services for needy-poor people (social market project, soup kitchens):

The welfare department provides aid for those in need… We have a welfare store. It is a smart system. People in need can shop there like a regular store without feeling embarrassed. … Being a Turkish citizen is a requirement to receive a card; but we do not turn down immigrants. We also have soup kitchens in our neighborhood community centers (Semt Konakları). (Directorate of Foreign Affairs, 3 April 2018)

The Fatih municipality focused on migrants, minorities and people with disabilities (African Football Team, Disabled Community Center, Sulukule Art Academy). Meanwhile, the Beşiktaş Municipality established an Expat Center to provide help for ‘foreigners’ that are defined as ‘foreigners visiting, studying, working or residing in Istanbul and specifically in Beşiktaş’ (http://en.besiktas.bel.tr/section/expatcenter/). Although the center did not distinguish between foreigners that were temporarily in Beşiktaş on a voluntary basis and migrants that had settled in the district, the center was mainly frequented by students who were in the city for short periods of time. Generally, the municipalities had not developed special services for long-term migrants such as Syrian migrants even though they housed a considerable number of migrants. Officials did emphasize, however, that they could benefit from the general services that were offered.

Also, regulations and legislations became a major determinant for the inclusion of the communities the municipalities served at the local level:

The efforts in Turkey are usually shaped by legislation… The spatial reflections of diversity are merely what is in the legislation… like the legislation for the disabled or the planning standards… The regulation resorts to the categorization of services by population groups and age groups. (Beşiktaş Municipality, Directorate of Plan and Projects, 23 February, 2018)

But sometimes the perception of regulations and legislation could be understood differently by municipalities. For instance, the Municipality’s Law of ‘Fellow-citizenship’ was understood in a different way by different municipalities and affected their view on Syrian migrants:

If I speak about my own field, the municipality should provide certain social policies and social services to the disadvantaged. It should do this by the authority granted by laws. Such an authority is already granted in the Municipal Law. I mean, the municipality does not act on its own… The thing about Syrians is different. The Municipality serves its citizens according to the Fellow-citizenship principle, but they are not citizens, this is the problem. (Beşiktaş Municipality, Directorate of Social Welfare Affairs, 8 March 2018).

The Municipal Law no. 5393 addresses all residents in a district. Services should be provided without discrimination. It enables the execution of activities from Amateur Sports Clubs to the disabled, the poor, low-income groups in need of aid, students, educational and cultural activities, etc. without discrimination. There is no special title there, it only mentions residents. Therefore, regardless of being Syrian or immigrant, everyone is a resident.

(Do immigrants have resident status?)

If they have an association or if they apply in person, we do our best to help them. Of course, the law does not especially identify who the disadvantaged are and does not require a special treatment to them. At the moment, there may be a law or certain arrangements specific for Syrians. Yet, these are laws and studies related to their specific situation and problems. In any case, they are now residents; and therefore, they are considered as well …. (Fatih Municipality, Directorate of Culture and Social Affairs, 12 March 2018)

Besides minorities were represented in Beşiktaş and Fatih Municipality by asking their opinions directly for planning services or for other services in the municipality:

In terms of participation, we always act in cooperation with the General Directorate of Foundations. Projects are shaped according to their opinion. Even the general directorate cannot assert a direct authority on Minority Foundations. Their opinions are asked directly. Let’s say if an Armenian Foundation is involved, we address them. The general directorate cannot make decisions ex officio either. … the law forces us to ask their opinion if their property is involved. (Fatih Municipality, Directorate of Plan and Project, 12 March 2018)

There are many non-Muslim groups in Beşiktaş, and this is how we carry out our efforts with them: They have representatives who are employed by the municipality. There are other people who coordinate the relationships and keep in touch with the municipality. … This way, they contact them and ensure that they participate in these services by bringing minorities and the municipality together. (Beşiktaş Municipality, Social Welfare Affairs, 8 March 2018).

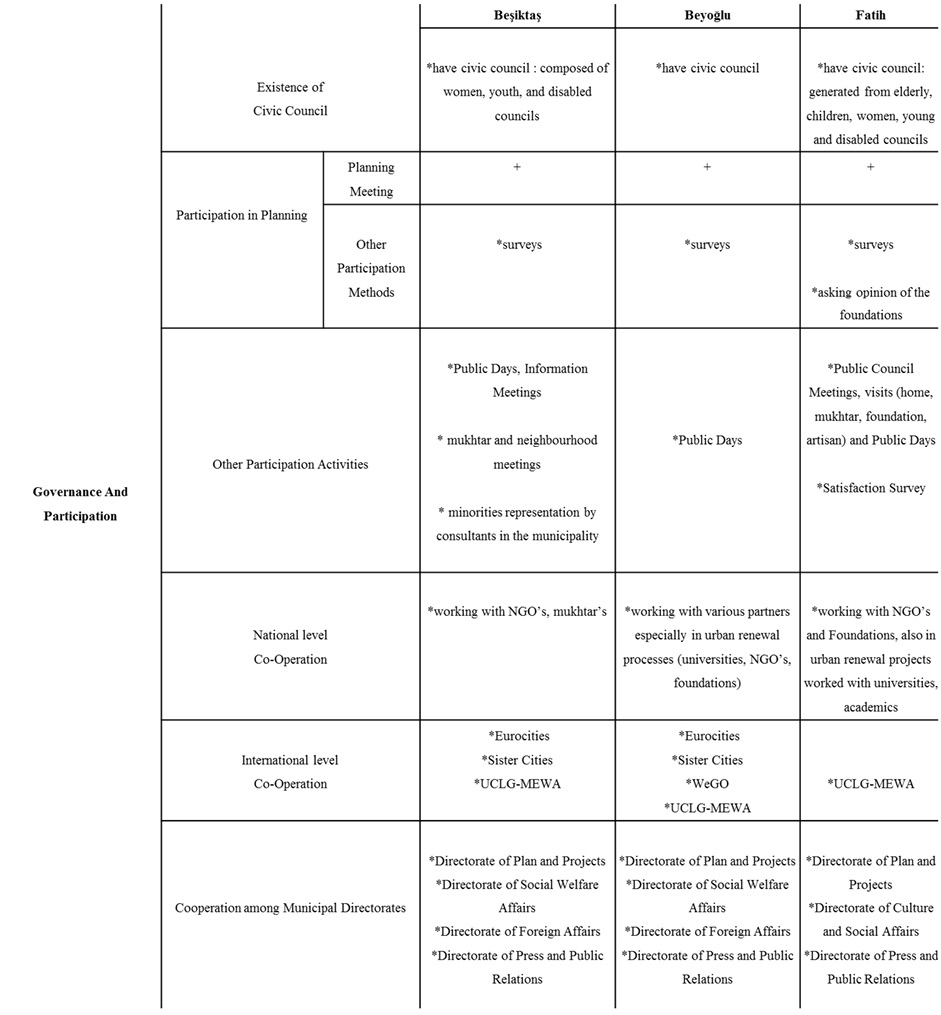

The study’s final consideration was the level of public participation in decision-making offered to each municipality’s diverse communities (Table 4). First of all, each municipality had a civic council that was stipulated by law, which could enable higher levels of participation, though the decisions made in these councils were not binding. Although disadvantaged groups were supposed to be represented by civic councils through sub-councils— such as those for youth, elderly, women or disabled residents— these councils were not sufficient for representing the many diverse groups in these districts, such as minority groups or migrants. Public participation was also supported through planning meetings and opinion surveys as part of regular planning activities. Other public participation methods included open days where the public was encouraged to express their opinions and make requests regarding planning initiatives and services.

To strengthen inclusionary governance and practice, national and international cooperation was established in each municipality. At the international level, each municipality is part of the UCLG-MEWA network which aims to create inclusive societies. However, none of the municipalities had any special projects established under this agreement. Although Beşiktaş and Beyoğlu municipalities were part of the Eurocities network, their membership was only limited to participating in the network’s meetings and presenting best practice projects. For instance, Beşiktaş Municipality presented and published their projects for the elderly3 and Beyoğlu municipality published their community center (semt konakları) projects for women and children in the Eurocities website as their best practice. On the other hand, Beşiktaş and Beyoğlu municipalities mentioned that they developed projects jointly with sister/twinned cities [Beyoğlu municipality mentioned Herne (Germany) municipality and Beşiktaş mentioned Mannheim Municipality (Germany)]. Eurocities encouraged such arrangements and helped Beyoğlu municipality to set up an agreement with Mannheim Municipality.

Officials in the Fatih and Beyoğlu municipalities viewed urban renewal projects in their districts, which were led by the national government, as opportunities to provide services for diverse groups. These projects had the potential to give deprived areas the means to be redeveloped thus offering disadvantaged groups better living conditions. The municipalities had limited flexibility in these projects because they were strictly defined by the planning regulations (Laws 3194, 5396, 6306 etc.). The officials used the tools offered by these regulations (surveys, public meetings, social analysis) to include different segments of the population and sought to provide public benefit to all their constituents. However, the two municipalities were not able to develop strategies for inclusive practices in the urban renewal projects, which led to detrimental consequences for diversity.

In brief, according to scholars diversity in the long term leads to equality (Reeves 2004, Fainstein 2005), cohesion (Tasan-Kok et al 2014) and economic growth (Jacobs 1961; Talen 2006; Florida 2012; Granovetter 1983; Putnam 2007). The study demonstrated that, in the three municipalities examined, national policy and legislation are essential to achieve the stated benefits. Furthermore, each municipality had incorporated diversity practices in their communities. These practices were carried out mainly to serve ‘disadvantaged’ groups. Diversity (çeşitlilik) was defined by the participants in the study however it was not defined or mentioned as an asset in each municipalities strategic plan:

I think, ethnic and religious differences that cohabit with respect constitute richness for the country, and I am not afraid of it. You go abroad, and there are all kinds of people. They generate added value. I personally believe in such a diversity. People can identify themselves however they want. I believe it should remain as a richness for this country. Let the people who stroll through İstiklal Street be all different. The more diversity there is, I consider it a gain for this country (Beyoğlu Municipality, Directorate of Reconstruction and Urbanism, 8 February 2018)

When we looked at the three municipalities, although two of them have membership with Eurocities and three of them with UCLG-MEWA, they were not fully aware of the importance of these networks. Also, although these three municipalities are neighboring municipalities, they did not have any collaborations with each other. Overall the different directorates in municipalities (planning, social services, public relations) had various responsibilities to provide inclusive services however the collaborations among departments was weak and the three municipalities were not able to develop common strategies for inclusive practices. On the other hand, two of the municipalities (Beşiktaş and Beyoğlu) have some collaborations with their international sister cities. So, this shows their potential to use the networks with other cities.

Conclusion

This study has shown that migrants from other countries as well as migrants from different parts of Turkey were regarded as diverse groups, which could be indicators for the notions of super diversity and hyper-diversity in investigating the governance of diversity. The increase of diversity in metropolitan cities, particularly due to the recent surge in international migration across the world, offers economic and social opportunities. However, changing social demographics at the local level could result in tension among the different groups. The case of the Beşiktaş, Beyoğlu and Fatih Municipalities in Istanbul demonstrates that local knowledge of constituents and direct accountability to their inhabitants offer these institutions the incentive to focus on particular groups within their districts (eg. young, elderly, needy, LGBT, Syrian migrants) that require inclusive services. Generally, the focus of each municipality resulted from the history of the municipality, its identity and the characteristics of the community that lived in the district. The municipalities service provision to diverse groups generally resulted from identifying and serving disadvantaged groups in their district; but the groups that were defined as disadvantaged differed. When confronted with the complexity of super or hyper-diversity the district municipalities have sought to bring forth their own political and historical identities in reaching out to their communities and focused on providing inclusive services through the designation of ‘disadvantaged groups.’

The three case studies give insight to debates on equality and inclusiveness. In providing an inclusive approach to planning, governance and implementation, the local municipalities have stated their need to abide by national laws and regulations. They have supported and expanded the opportunities these directives offer in accommodating diverse needs. The municipalities focused on the equal treatment of all and providing public benefit (kamu yararı) to their residents. However, the definition of fellow-citizenship was interpreted differently by the three municipalities; the obligation to serve all residents who wanted to benefit from municipal services due to the fellow-citizenship (hemşehricilik) law could also be interpreted as focusing on ‘naturalized citizens.’ National laws that stipulate the preparation of strategic plans, the establishment of public councils and regulations that require public planning meetings have created an opportunity for more inclusive planning processes. Participation through public planning meetings or through public councils is crucial, as they are important instruments for decreasing injustices and accommodating diversity in cities when diverse groups are equally represented. However, the representation of migrants in the participation process has been problematic, as their acceptance as fellow-citizen (hemşehri) could differ from one municipality to another. The notion of diversity and equality appear together in the three districts. However the concern for equality by the district municipalities has, in some cases, led to the oversight of the particular needs of Syrian migrants. On the other hand, religious or ethnic minorities who have been in these districts since the Ottoman Empire are included directly or through their representative foundations. The acknowledgment and institutional representation of diverse groups creates the opportunity for a higher degree of participation within planning processes which creates dialogue both within the groups and with the administrative bodies that is stipulated in discussions regarding interculturalism.

The two municipalities that are part of the EU-funded Eurocities have benefited from the network as a way to share and promote their inclusive policies. Eurocities and the liaisons that it enabled have provided an opportunity to exchange information and for the municipalities to promote themselves internationally. In this regard, this study also emphasizes the importance of international networks as problems are becoming similar globally, and the convergence of policies between countries in EU-related networks would further dialogue at both the international and national levels. The key to creating more effective inclusive practices at the local level would be in identifying inclusive planning as a strategy within the municipalities with the participation of all responsible departments. These strategies could further be strengthened by partnerships among local municipalities that address similar challenges. In this regard, a multi-level governance which emphasizes on local practices strengthened by national laws and international co-operations could be an ideal solution to create an inclusive environment for diverse communities.

Note on the Authors

Semahat Ceren Say graduated from the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Istanbul Technical University in 2015. She received her MS in urban planning from Istanbul Technical University in 2018. Her master’s thesis focused on urban diversity practices of local municipalities in Istanbul. Her main research interests are urban diversity, governance and inclusive planning. Email: sayceren@gmail.com

Dr. Başak Demireş Özkul is an assistant professor at Istanbul Technical University, Department of Urban and Regional Planning. She completed her PhD (2011) at the Bartlett School of Planning, UCL where she was also a member of the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis. She received a Master of City Planning (2001) from the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. She is a graduate of Istanbul Technical University in the Department of City and Regional Planning. Email: demiresozkul@itu.edu.tr

References

ABDOU, L. H., and A. Geddes. 2017. Managing Superdiversity? Examining the Intercultural Policy Turn in Europe. Policy & Politics 45 (4): 493-510.

AFAD. 2013. Türkiye’deki Suriyeli sığınmacılar, 2013 saha araştırması sonuçları. TC Başbakanlık Afet ve Acil Durum Yönetimi Başkanlığı.

AMIN, A. 2002. Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity. Environment and Planning A 34 (6): 959-980.

–––. 2013. Land of Strangers. Identities 20 (1): 1-8.

BEATLEY, T., and K. Manning. 1997. The Ecology of Place: Planning for Environment, Economy, and Community. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

BERRY, J. W. 2011. Integration and Multiculturalism: Ways Towards Social Solidarity. Papers on Social Representations 20 (1): 2-1.

BEŞIKTAŞ MUNICIPALITY. 2015. Strategic Plan 2015-2019.

BEYOĞLU MUNICIPALITY. 2015. Strategic Plan 2015-2019.

BIEHL, K. S. 2015. Spatializing Diversities, Diversifying Spaces: Housing Experiences and Home Space Perceptions in a Migrant Hub of Istanbul. Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 596-607.

BURDETT, R. 2009. Istanbul: City of Intersections. Urban Age.

CAPONIO, T. 2018. City networks and the multilevel governance of migration: Towards a research agenda. In: T. Caponio, P. Scholten, and R Zapata-Barrero, eds., The Routledge Handbook of the Governance of Migration and Diversity in Cities, Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

CLG – DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT. 2010. Evaluation of the National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal: Local Research Project. London HMSO.

DANIŞ, D. & NAZLI, D. 2019. A Faithful Alliance Between the Civil Society and the State: Actors and Mechanisms of Accommodating Syrian Refugees in Istanbul. International Migration 57 (2): 143-157.

DOWNING, J. 2015. Contesting and Re-negotiating the National in French Cities: Examining Policies of Governance, Europeanisation and Co-option in Marseille and Lyon. Fennia-International Journal of Geography 193 (2): 185-19

DUXBURY, N., and M. S. Jeannotte. 2013. Global Cultural Governance Policy. In: The Ashgate Research Companion to Planning and Culture. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

ERAYDIN, A., Ö. YERSEN, N. GÜNGÖRDÜ, and I. DEMIRDAĞ. 2014. Urban Policies on Diversity in Istanbul, Turkey.

ERAYDIN, A., I. DEMİRDAG, F.N. GÜNGÖRDÜ, and Ö. YENIGÜN. 2017. Dealing with Urban Diversity: The Case of Istanbul.

ERDOĞAN, M. 2015. Türkiye’deki Suriyeliler: Toplumsal kabul ve uyum. İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

ERDOĞAN, M., & KAYA, A. 2015. Türkiye‟ nin Göç Tarihi. İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

ERDOĞAN, M. 2017. Kopuştan uyuma kent mültecileri. In: Disengagement to Adaptation City Refugees. İstanbul: Marmara Belediyeler Birliği Kültür Yayınları.

FAINSTEIN, S. S. 2005. Cities and Diversity: Should We Want It? Can We Plan for It? Urban Affairs Review 41 (1): 3-19.

FAIST, T. 2009. Diversity–a new mode of incorporation?. Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (1): 171-190.

FAIST, T., & A. ETTE. 2007. The Europeanization of National Policies and Politics of Immigration: Between Autonomy and the European Union. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

FATIH MUNICIPALITY. 2015. Strategic Plan 2015-2019.

FLORIDA, R. 2012. The Rise of the Creative Class–Revisited: Revised and Expanded. Basic Books.

FRASER, N. 1990. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy”. Social Text, 25/26: 56-80.

GRANOVETTER, M. 1983. “The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited”. Sociological Theory 1: 201-233.

HEALEY, P. 1997. Collaborative Planning, Shaping Places in a Fragmented Societies. Vancouver: UBC Press.

IÇDUYGU, A. 2015. Syrian refugees in Turkey: The long road ahead. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

IÇDUYGU, A., & AKSEL, D. B. 2013. Turkish migration policies: A critical historical retrospective. Perceptions 18 (3): 167.

IMM. 2015. Strategic Plan 2015-2019.

ISTKA. 2015. Istanbul Regional Plan 2014-2023.

JACOBS, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage.

JOPPKE, C. 2007. Beyond National Models: Civic Integration Policies for Immigrants in Western Europe. West European Politics 30 (1): 1-22.

KIRISCI, K. 2014. Misafirliğin ötesine geçerken Türkiye’nin “Suriyeli mülteciler” sınavı. USAK (çev: S. Karaca).

KOCA, A., YIKICI, A., KURTARIR, E., ÇILGIN, K., ÇOLAK, N., & KILINÇ, U. 2017. Kent Mülteciliği ve Planlama Açısından Yerel Sorumluluklar Değerlendirme Raporu: Suriyeli Yeni Komşularımız, İstanbul Örneği.

KOÇAK, S. Y., and A. EKŞI. 2010. Katılımcılık ve Demokrasi Perspektifinden Türkiye’de Yerel Yönetimler. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 2010(21).

KOENIG, M., & P. de Guchteneire. 2017. “Political Governance of Cultural Diversity”. In: P. Haschke, ed. Democracy and Human Rights in Multicultural Societies. London: Routledge.

KRAUS, P. A. 2012. The Politics of Complex Diversity: A European Perspective. Ethnicities 12 (1): 3-25.

KURBAN, D. 2016. Country Report: Non-Discrimination Turkey. Brussels: European Commission

KYMLICKA, W. 2012. Multiculturalism: Success, Failure and the Future. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

LANDRY, C., and P. WOOD. 2012. The Intercultural City: Planning for Diversity Advantage. Earthscan.

MASSEY, D. 2004. Geographies of Responsibility. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86 (1): 5-18.

MCDOWELL, L. 1999. “City Life and Difference: Negotiating Diversity”. In: J. Allen, D. Massey and M. Pryke, eds., Unsettling Cities. New York: Routledge.

PAYRE, R. 2010. The importance of being connected. City networks and urban government: Lyon and Eurocities (1990–2005). International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34 (2): 260-280.

PUTNAM, R. D. 2007. E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty‐first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies 30 (2): 137-174.

REEVES, D. 2004. Planning for Diversity: Policy and Planning in a World of Difference. Routledge.

SANDERCOCK, L. 2000. When strangers become neighbours: Managing cities of difference. Planning Theory & Practice 1 (1): 13-30.

–––. 2003. Planning in the ethno-culturally diverse city: A comment. Planning theory & practice 4 (3):319-323.

SASSEN, 1994. Global City. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

SAY, S.C. 2018. Evaluating Urban Diversity Practices of Local Municipalities in Istanbul: A Case Study of Beşiktaş, Beyoğlu and Fatih Municipalities (Unpublished master’s thesis). Istanbul Technical University, Institute of Science And Technology, ISTANBUL.

SCHILLER, M. 2016. European Cities, Municipal Organizations and Diversity: The New Politics of Difference. Springer.

SCHOON, D. V. D. 2014. ‘Sulukule is the gun and we are its bullets’: Urban renewal and Romani identity in Istanbul. City 18 (6): 655-666.

STEVENSON, D. 2013. Culture, planning, citizenship. The Ashgate Research Companion to Planning and Culture, 155-169.

TALEN, E. 2006. Design that enables diversity: the complications of a planning ideal. Journal of Planning Literature 20 (3): 233-249.

TASAN-KOK, T., R. van Kempen, R. MIKE, and G. Bolt. 2014. Towards hyper-diversified European cities: A critical literature review. Utrecht: Utrecht University, Faculty of Geosciences.

UCLG-MEWA. 2017. UCLG-MEWA Introductory Booklet [Leaflet].

UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENT PROGRAMME. 2008. The State of the World’s Cities 2008/9: Harmonious Cities. London: Earthscan, 2008.

VERTOVEC, S. 2007. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024-1054.

UNSAL, B. O. 2015. Impacts of the Tarlabaşı urban renewal project:(forced) eviction, dispossession and deepening poverty. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 193: 45-56.

UYSAL, M. T., & KOROSTOFF, N. 2015. Tarlabaşı, Istanbul: a case study of unsustainable urban transformation. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 194: 417-426.

WOODS, A., & KAYALI, N. 2017. Suriyeli Topluluklarla Etkileşim: İstanbul’daki Yerel Yönetimlerin Rolü. İstanbul Politikalar Merkezi.

YERSEN, Ö. 2015. A study on governance arrangements focusıng on urban diversity: the case of Beyoglu–Istanbul (Doctoral dissertation). Middle East Technical University, Institute of Science And Technology, ANKARA.

YOUNG, I. M., and D. S. Allen. 1990. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

New Diversities • Article 22, No. 1, 2020

Enabling Diversity Practices in Istanbul

Guest Editors: Semahat Ceren Say and Başak Demireş Özkul

(Istanbul Technical University)

- ISSN-Print 2199-8108

- ISSN-Internet 2199-8116

- For a list of participating authorities for Inticities please refer to http://www.integratingcities.eu/integrating-cities/projects/inti-cities, for Dive refer to http://www.eurocities.eu/integrating-cities/projects/DIVE, for Mixities refer to http://www.integratingcities.eu/integrating-cities/projects/mixities and for Implementoring refer to http://www.integratingcities.eu/integrating-cities/projects/Implementoring.

- Law related to Fellow-citizenship Article 13-Everyone is a fellow-citizen of the county which he lives in. The fellow-citizens shall be entitled to participate in the decisions and services of the municipality, to acquire knowledge about the municipal activities and to benefit from the aids of the municipal administration.

- For more information please refer to http://www.eurocities.eu/eurocities/allcontent/Cities-in-action-wellbeing-service-Besiktas-WSPO-9YEKQN