New Diversities • Volume 23, No. 2, 2021

Everyday Nationalism and Non-Traditional Christian Communities in Baku

by Yuliya Aliyeva

To cite this article: Aliyeva, Y. (2021). Everyday Nationalism and Non-Traditional Christian Communities in Baku. New Diversities, 23(2), 43-63. https://doi.org/10.58002/reev-7n02

Abstract: This article explores the non-traditional Christian Communities (NTCCs) in Azerbaijan and discusses the ‘situatedness’ of these ‘new’ religious groups in relation to the national authorities, local communities, and transnational evangelical movements. While contributing to the pluralization of the religious terrain in the post-soviet country, these transnational religious movements are perceived as disruptors, bringing complications to the established religious ‘status-quo’, and re-defining religion as a matter of personal choice rather than a nominal status acquired at birth. Drawing on ethnographic observations, the paper demonstrates how the production of the ‘patriotic narratives’ helps these communities to challenge the regime of ethnodoxy and adopt the ‘hybridized identity’ loyal to the tenets of Azerbaijani civic patriotism and committed to the goals of the transnational faith communities. The appropriation of the ideology of civic nationalism by the NTCCs can be perceived as one of the coping strategies used by these communities to negotiate for wider recognition and acceptance with the authorities and host communities.

Keywords: Azerbaijan, religious revival, non-traditional Christian Communities, civic nationalism, everyday nationalism, transnational faith communities

The final draft of this paper was submitted for consideration of the editorial committee of the “New Diversities” journal on September 1, 2020. Thus, it does not include information on activities of the NTCCs during the Second Karabakh war and in after-war period.

Introduction

In this article1 I explore the so-called non-traditional Christian Communities (NTCCs) in Azerbaijan and discuss the ‘situatedness’ of these ‘new’ religious groups in relation to the national authorities, local communities, and transnational evangelical movements. Drawing on my ethnographic research I argue that the members of these NTCCs are adopting the ‘hybridized identity’ which manifests itself in expression of the civic nationalism and emphasis on belonging to Azerbaijani nation along with display of devotion to transnational faith communities.

While numerous academic papers have addressed issues of religion and the religious in post-Soviet Azerbaijan, the vast majority focused on revival of Islam and the political implications of the growing number of Muslim communities in the country. But the revival of religion and the ‘religious’ is not limited to Muslim religious groups in all their heterogeneity. The numerous non-Muslim communities, either historically-situated or the outcomes of the new religious influences, produce their own post-atheistic narratives elaborating on how religious re-discoveries helped them to pursue the spiritual needs and mundane interests in the complex post-Soviet environment. My research focuses on the Protestant evangelic communities in Azerbaijan that are actively engaged in missionary work promoting the conversion to the evangelical Christianity in its polyphonic variety.

It is important to note that ‘religiosity’ for the majority people in Azerbaijan stands for a cultural foundation of their identity, a ‘heritage’ rather than strictly followed religious doctrine (Valiyev 2008, Goyushov 2008, Nuruzade 2016, Wiktor-Mach 2017, Darieva 2020). This phenomenon, for instance, was discussed in detail by Ayça Ergun and Zana Çitak (2020) claiming that the secularism and non-Muslim religious identity constitute the foundation of the national identity in post-Soviet Azerbaijan whereas “[r]ather than worship, ritual, and practice, Islam represents a sort of cultural glue, bonding Azerbaijanis to their past and connecting them to their ancestors” (19). This thesis on prevalence of secular values can be extended well beyond the Islamic circles to representatives of other ethnic and religious groups residing in Azerbaijan. While the religious landscape of Azerbaijan is notable for its plurality and the centuries-old co-existence of ‘traditional’ Muslim (Shia and Sunni), Jewish (Mountainous, Ashkenazi and Georgian) and Christian (Orthodox, Lutheran and sectarians, such as Molokans, Baptists, etc.) communities, for the majority of modern Azerbaijani citizens religion acts mostly as marker of belonging and not the manifestation of individual religiosity. In this respect, new religious Christian and Muslim communities that are linked with transnational religious movements are acting as disruptors; they are bringing complications to the established religious ‘status-quo’ and are re-defining religion as a matter of personal choice rather than a nominal status acquired at birth.

These disruptions bring a new dynamic to the socio-political life in the country and are often defined as a ‘threat’ to the stability and social cohesion within the country. While officially the Azerbaijani government replaced restrictive Soviet atheist ideology with the more moderate religious policies, welcoming religious pluralism and ‘multiculturality’ in the country, the ‘non-traditional’ sects, that do not belong to the ‘indigenous’ religious communities outlined in the official discourse as mainstream Islam, Orthodox Christianity and Judaism, are under the constant scrutiny and control. The authorities are specifically cautious about the operations of the so-called ‘non-traditional’ Muslim religious communities which are often accused of pursuing long-term political goals or engagement in terrorist networks (Bashirov 2018). Even the political aspirations of the so-called non-traditional Christian sects are quite insignificant or totally irrelevant; their activities are also closely monitored and are often restrained. In the first part of the article I discuss the complex relationship between the state and NTCCs and illustrate how they have evolved in light of internal and external influences and with the growing visibility of evangelical groups. In the second part, I focus on the practices of ‘everyday nationalism’ among evangelical Christians which shape their everyday life experiences and how they navigate expressing religious and nationalistic sentiments.

‘Non-Traditional’ Religious Communities and Their Uneven Relationship with the State

Azerbaijan is often praised for being a “largely successful and functioning laboratory for a civic nation and moderate Islam in the modern world” (Cornell, Karaveli, Ajeganov 2016: 112). The majority of recent scholarship on religion, politics, and society in Azerbaijan has focused on the complexities of national and religious identity in the post-Soviet context where the ‘religious’ was always equated with the dominant trend of Islamic revival in the country. Many scholarly debates were dedicated to the discussion on how radical or far-reaching such a revival can be and whether it poses a challenge to the well-established traditions of secularism threatening the image of Azerbaijan, as Svante Cornell (2011) puts it, as “the most progressive and secular-minded areas of the Muslim world” (268). While the Islamic manifestations of religiosity were studied in all their variety of forms starting from the ‘nominal’ cultural identity to the non-traditional Islamic movements, the non-Muslim religious trends were seldom coming to scholarly attention and were probably deemed as scant and thus insignificant (Alizadeh 2018). The existence of these non-Muslim groups produces noteworthy internal controversies testing the limits of the ‘new unifying national ideology’ offered by the political regime. Depending on the official status of these groups, in terms of their ability to secure the state permission for operations, their showcases are often used either to add up to the international promotion of ‘official version’ of Azerbaijan as a unique example of peaceful coexistence and collaboration (Sadiqov 2017) or to spark the criticism on the government for creating the most sophisticated and intelligent system to suppress religious freedoms (Open Doors 2018). I will later discuss the nature of these uneven relationships with the state and how it has been changing along the transformation of the government’s ideological doctrine.

Figure 1. The Church of the Saviour (Azerbaijani: Xilaskar kilsəsi; also known as the kirkha). © Yulia Aliyeva, 2019.

According to official estimates, less than five percent of the nation’s nine million citizens identify with non-Muslim religious groups, such as Orthodox Christians, Jews, Krishna, Baha’i, other Christian denominations including Roman Catholic, Alban-Udi and Protestant Churches2. The major problem with the official religious statistics is its primordial nature resting on the assumption that ethnic belonging predetermines one’s religious affiliation. Following this logic, the data on ethnic groups collected during the census is converted into the religious affiliations. Thus, the majority of ethnic Azerbaijanis, Talyshs, Lezgi are automatically assigned into the category of Muslims, Slavic ethnic groups (Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians) into Orthodox Christians, Germans to Lutheran Protestants, etc. As such, ‘ethnodoxy’, defined by Karpov, Lisovskaya and Barry (2012: 639) as “an ideology that rigidly links a group’s ethnic identity to its dominant faith” continues to play the key role in assigning people into the statistically pertinent faith categories. However, with the growing pluralization of the religious space in the post-Soviet Azerbaijan, a belief that one is ‘born into the faith’ is being challenged by groups actively engaged in proselytizing offering a range of experiences be it conversions to Salafi Islam or evangelical Christianity. These “conversion-led movements,” as defined by David Lehman (2013), offer similar experiences to their followers regardless of one’s religious denomination sharing “one factor in common: their followers describe their adherence in terms of a life-changing conversion experience.” However, it is very difficult to judge the scope and impact of these new religious influences on social and political developments in the country, what often opens the floor for speculations and security concerns.

The focus of the current paper are the so-called ‘nontraditional’ Christian communities (henceforth NTCCs), uniting the groups which are also commonly labeled as neo-Pentecostal, Charismatic or Evangelical. I prefer to use the term NTCCs in the Azerbaijani context since it encompasses all evangelical movements disregarding the theological differences between them and the length of their historical presence in Azerbaijani. They are contrasted with ‘traditional’ churches such as Orthodox, Catholic or Lutheran, defined by a distinct hierarchy and traditional liturgy, whose presence in Azerbaijan is supported by the direct appointments from the respective religious centers. The NTCCs are more autonomous movements. They maintain close ties with transnational evangelical networks but enjoy decentralized religious authority, urging them to pave their own ways in the local context.

Categorizing religious groups into ‘traditional’ and ‘nontraditional’ is widespread in the post-Communist Eastern Europe and it is closely associated with the idea of the revival of religious traditions outlawed by the atheistic Soviet regime. But while in the certain post-Soviet countries the division of religious groups into ‘traditional’ and ‘nontraditional’ was incorporated into the legislative framework (Aitamurto 2016; Račius 2020), the state officials in Azerbaijan recognize this division as ‘conventional.’ For instance, the Deputy Chairman of the State Committee on Work with Religious Associations (SCWRA), Siyavush Heydarov, talks about certain societal misconceptions in an interview: “… It is sometimes misunderstood in society that all non-traditional religious communities are unacceptable, or that their activities are destructive. This approach is not valid. We emphasize that the state‘s attitude towards religious communities varies not because they are traditional or non-traditional, but because they do or do not comply with the existing laws.”(Bingöl 2018) Thus, in the context of post-Soviet Azerbaijan, much greater importance is placed on the ‘official status’ of the religious groups as ‘registered’ and ‘unregistered’, approved or disapproved by the state authorities, as acquisition of the state registration provides a formal endorsement for operations in the country.

The findings presented in the article draw upon the fieldwork I conducted in Baku city from January to June of 2019. My fieldwork included visits to the charismatic church ‘Word of Life’, the neo-charismatic Vineyard church, Lutheran church, Presbyterian (positioning as Azerbaijani-language chapter of the Lutheran church), Seventh Day Adventists, ‘New Life’ Evangelical church as well as my brief encounters with the members of New Apostolic and Baptist churches3 and one leader of the unregistered religious community located in the regional center of Azerbaijan. Some of these churches were established by foreign missionaries, others by local religious leaders, often spinning off from other local NTCCs. Although all these churches have their own atmosphere, repertoire of worship, and methods of communication with parishioners, they are offering the adherents spiritual renewal along with a strong sense of community in a very similar manner, strengthening the faith through the nets of intimate interpersonal interactions beyond the walls of the church. All of these communities, except for the Lutheran church, are engaged in missionary work with different intensity and success and see it as a moral obligation of the community members. The history of the Baptist, Molokan, Seventh Day Adventist and the Pentecostalist communities in Azerbaijan is rooted back to when the territory of Azerbaijan was on the periphery of the Russian Empire, where the ‘undesirable’ Christian groups, often in opposition with the Orthodox Christianity were exiled. The ethnicity of these early settlers was mostly of Slavic origin (Russians, Ukrainians), however, some German colonizers splitting from Lutheran churches were also actively engaged in religious pluralization of the field (Alizadeh 2018). During Soviet times the devotees of these communities suffered years of prosecution and condemnation, gradually resuming the permission for religious practice under the close surveillance starting in the 1960s (Hasanli 2018). Nowadays, these churches are treated as ‘traditional’ or as indigenous groups and are considered to be part of the common national historical heritage.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union brought about a vibrant dynamic to the religious field. One of the first legal acts was adopted in Azerbaijan following the dissolution of the Soviet Union was the law „On freedom of religious beliefs „ (August 20, 1992) which guaranteed individual right to determine and express his/her view on religion and to execute this right. The Law opened the possibility for free practice of religion, attendance of religious services in mosques and churches, and public celebration of religious holidays or commemorations. The restrictions in which one had to compromise one’s career in the communist party with one’s religious beliefs were lifted, which led to a ‘re-discovery’ of one’s religious roots. For instance, one of the first visits of the late President Heydar Aliyev (former KGB general) after becoming the President of the independent Azerbaijan was a pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca.

As JDY Peel (2009: 184) rightly argues, “the opening up of the Soviet bloc to the new religious influences has occurred at a time when, owing to religious development elsewhere in the world, transnational flows of religious influence have become much more polycentric and multi-directions than we have hitherto thought of them”. Azerbaijan was no exception, as these transnational influences brought a new life to the ‘traditional’ Christian communities or helped many to discover a new ‘religious’ identity. The geography of the Christian missionaries in Azerbaijan was extremely diverse stretching from the Nordic countries to South Korea, from the United States to Belarus, from the UK to Russia. Some of them joined existing communities, bringing financial flows, literature and even new practices to the communities which, for decades, were disentangled from fellow worshippers. Some foreign missionaries started new churches, bringing new spiritual experiences to a country torn by the war, poverty and social tensions. These neo-Pentecostal or Charismatic movements were offering people a spiritual renewal and hope for a better life and well-being now, running various support programs from foodbanks to the needy to patronage services to the elder and empowering programs for youth such as computer literacy and English language courses. The respondents from the interviewed churches (Lutheran, Baptist, Seventh Day Adventist, Orthodox Christian, Word of Life) recall the 90s as a “Golden era.” The number of worshippers in all Churches proliferated rapidly, but ‘missionary’ churches were particularly successful, building up their communities from ‘scratch.’ The churches were serving not only the close circle of their adherents but provided humanitarian assistance to the population in general, targeting the most vulnerable circles: the elderly, IDPs and refugees. Old photos featuring missionary leaders jointly with the President Heydar Aliyev from the mid-90s still serve the communities as a justification that their in-country presence was approved in the highest echelons.

However, starting toward the end of the 1990s and beginning in 2000, government officials’ attitudes towards NTCCs began to change. The report about including Azerbaijan into an “Evangelization 2000” program introduced by foreign missionaries was featured in a book by Ramiz Mehdiyev (2005). He was the former Chief of Presidential Administration and considered to be one of the key government strategists at that time. The frightening accounts shared the far-reaching plans of converting every fifth Azerbaijani to Christianity by 2010 and Azerbaijan as a whole by 2040. Mehdiyev also accused missionaries of spreading ideas that stained Islam (191). Given geopolitical location of Azerbaijan, the report assumed that the missionaries were trying to make use of Azerbaijan in their geopolitical battle and their goal was to strategically convert the country into the base area for Western countries to expand their influence further to Iran, Turkey and Central Asia (192). Later, in 2011, these concerns reemerged in Milli Majlis (National Parliament) by the deputy of the Caucasus Muslims leader Sheihulislam Allahshukur Pashazade, Haci Sabir Hasanli, calling for stricter regulations of the Christian missionary activities in Azerbaijan (Milli Majlis, Stenogram 2011).

In media reports, the converts were often accused of acting in the interest of ‘alien forces.’ For instance, in 2013, at least three young male followers of the Jehovah Witnesses were prosecuted for ‘evading military service’ and received sentences ranging from nine months to one year in prison (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada 2016). The newspaper reports accused them of befriending the enemies and betrayal to the state (Media TV 2015, Alekperova 2017). Thus, repressive measures against the non-traditional Christian communities were justified by the need to protect national interests and the local population from the hostile forces. Quite often, the media reports did not account for any differences between the NTCCs, placing Jehovah Witnesses and evangelical Christians into a box and treating them as a single entity managed from one center that knows how to skillfully penetrate the local social fabric. The degrading label ‘sect,’ inherited from Soviet times and associated with illegal religious practices, was widely used in media reports to stress the ‘evil’ and dangerous nature of these religious groups. The police raids were regularly reported in the media indicating how the law enforcements is protecting the citizens from ‘unwanted influences’ and help the ‘brainwashed’ to go back to ‘normal’ lifestyle. The level of repression varied, and the respondents suggested that they were often harsher against the Azerbaijani-language chapters of the NTCCs who were accused of proselytizing among the Muslims. The prosecutions and intimidations of the adherents of the NTCCs were regularly condemned in the embassies and international organizations’ reports, which criticized the government for violating the freedom of religion.

New regulations and policies to control religious communities’ operations in Azerbaijan were put forward with the establishment of the SCWRA in 2001. One of the principle tools of control was the introduction of the obligatory registration procedures for all religious communities, regardless of denomination. The registration procedures were harshened in 2009, as all previous registered organizations were forced to re-register by providing the application documents that detailed the specific location where worship would take place, as well as passport details of at least fifty adult followers registered (propiska) within that locality. Performance of worship in the places outside of the location indicated in the registration documents was prohibited. Although the regulations are equally applied to all religious communities, the numerous accounts suggest that the registration process for ‘non-traditional communities’ was more challenging than for traditional ones, resulting in prolonged procedures or even court settlements. The SCWRA also reviewed all religious literature (printed, video and audio) that had been imported or was published in Azerbaijan, and issued control marks (nəzarət markası) for the literature, which is allowed for sale and distribution in Azerbaijan. The new rules prohibited foreigners in church leadership (except a special arrangement with Lutheran and Catholic churches) and open proselytism.

However, after 2013, the government stance with regard to the NTCCs got milder and moved from the ‘prosecute and restrict’ to ‘regulate and control.’ The change in the attitude is attributed to the launch of the so-called ‘Politics of Multiculturalism,’ which promoted religious tolerance as a unique feature of the post-Soviet Azerbaijan.

According to Elshad Iskanderov, the Chairman of SCWRA in 2012-2014 and presumably one of the architects of the “Multiculturalism policy”: “Tolerance is an integral part of the national identity of the Azerbaijani people and its wealth is much more valuable than the oil” (Abdullayeva 2013). Thus, the government started ‘exporting’ the image of ‘Multiculturalism,’ turning it into an asset to improve the country’s image in light of the negative publications and resolutions of international organizations, condemning the authoritarian governance and violation of human rights. The international scholars were invited to explore the ‘unique’ character of Azerbaijani multiculturalism, defining it as a ‘third way,’ alternative to ‘melting pot’ and ‘isolation model’ (Șancariuc 2017), teaching Europe “a lesson” “about ways to protect minorities without compromising the values of the majority of the population” (Stilo 2016).

Whereas the politics of ‘multiculturalism’ was clearly a project informed by the foreign agenda of the government, it started to impact the local environment. Since the proclaimed government policy was not in line with the repressions against NTCCs and critical reports condemning the prosecutions were still being released, the government began to readjust. By the end of 2015, the twelve Christian Communities had been registered by the state, including the controversial Jehovah Witnesses community. However, all registered communities are located in Baku and big cities of Azerbaijan, such as Ganja and Sumgayit4, pointing to the challenges associated with registration of the communities located beyond urban areas. This disparity is often attributed to the insufficient number of parish members in these communities that qualify them for registration. However, some of the informants mentioned a lack of acceptance of the converts in the rural areas, which are organized along the strong horizontal community ties and higher level of intolerance of the local authorities. This resistance of the local communities can make people abandon their newly-acquired faith or practice in secrecy, maintaining the ties with the group located in big cities. One of the interviewers compared worshiping in Baku to ‘drinking water’ (su içmek kimi); people feel more at ease in the large metropole and can more freely engage in building their religious networks.

Figure 3. Emblem of Azerbaijan Bible society (open book of the backdrop of Azerbaijani flag). © Yulia Aliyeva, 2019.

The promotion of Multiculturalist policy in the country also impacted the issue of acess to the religious sources. For many years it was not possible to print any Christian literature inside the country. The importation of Christian literature from outside was strictly regulated and limited. However, since 2016 the Azerbaijan Bible Society has received its registration and opportunity to print not only the Bible, but other Christian literature and children’s books in Russian and Azerbaijani (still subject to approval by the authorities before going on sale). The Azerbaijan Bible Society also serves as an umbrella organization that carries out joint events for evangelical protestant communities of Azerbaijan and cooperates closely with the SCWRA. It also regards promoting unity among the Christian churches in Azerbaijan its mission. For instance, starting in 2016, the annual celebration of the Bible Day became an inter-confessional tradition with participation of all registered Christian Communities, including Catholic and Lutheran churches, with the exception of the Orthodox Christian Church, which tends to approach the cooperation with the ‘sectarians’ very carefully, although there are internal voices calling for closer engagement5.

The NTCCs got to literally ‘sit at the table’ as they started to be invited to events and official visits abroad organized by the SCWRA to demonstrate the politics of Multiculturalism ‘in action.’ According to Pastor Rasim Khalilov6, a Chairman of Azerbaijan Bible Society, the attitude towards the registered NTCCs has changed and they are now treated similarly to the ‘traditional’ ones:

In recent times everything has changed as if by the wave of the hand. And I think behind it is the competent policy of those in power, because they see that there is no danger coming from us, from Protestants and from Christians. We do not pursue illusions, such as taking over the power here, stand at the helm of government, and so on. We have our own themes: we love God, we pray to God, we praise God, we gather, we preach the Word of God… When people see this, sensible people at the top, they understand that they should not expect any insidious actions from these people, because we, as Christians, have gained trust to ourselves. Well, hence, if for twenty years starting in the nineties, we were respectively watched by the relevant authorities, and they saw what we can and what we cannot do. And our actions, they can be used for the good of Azerbaijan. If they help us, and we help them. And over the past five years, I have traveled and promoted the values of Azerbaijan, Christian values, values of tolerance, multiculturalism, about how Azerbaijan is changing today…

According to this passage, the past twenty years were the period when members of the NTCCs managed to develop competence by testing the limitations of the ‘religious market’ and gaining awareness of what was politically permissible. The important turn in approach towards the ‘non-traditional’ religious groups was the rhetoric of juxtaposition of the ‘peaceful’ NTCCs to the non-traditional Muslim religious communities, regarded as ‘dangerous’ and politically motivated by the Azerbaijani government. Admitting the awareness of the close surveillance of the religious groups in Azerbaijan, Pastor Rasim Khalilov stresses the value of trust, which NTCCs managed to build gradually, through a demonstration of loyalty towards the current political regime and observance of the legal regulations.

This general awareness of being closely watched and having ‘official spies’ within the congregation was acknowledged during an interview with many religious leaders. For instance, Pastor J. from one of the NTCCs welcomes this kind of surveillance to circumvent rumors and speculations: it helps him to reaffirm himself as an ‘innocent’ character of his religious community:

I know that my sermons are recorded and listened to by the authorities. But let them record and listen, I am totally fine with it. Let them know what happens here on Sundays and realize that we are quite harmless…

At the same time, over the last twenty years the political elite has built their own ‘religious’ competence and understanding of the value that NTCCs can bring in promoting Azerbaijan as a land of tolerance and peaceful co-existence of different faith groups. The close cooperation with the government bodies, mainly SCWRA and the Baku International Center for Multiculturalism, helped not only to secure a place for the NTCCs to have a ‘seat at the table’ but also made them active participants in propaganda evens. For instance, as Chairman of the Azerbaijan Bible Society, Pastor Rasim Khalilov was a member of the numerous official delegations organized by the SCWRA to Europe and the US, participating with various political platforms, including OCSE (Salamnews 2018). These activities were criticized by the religious watchdog organizations, which consider that the government is using NTCCs to promote the positive image of the country abroad, whereas the reality is not that ‘rosy’ and many communities, especially those based outside of the capital city Baku, are struggling to get registered and possibly operate at all (Open Doors 2018).

Another important factor, which potentially contributed to the improved relationship between the evangelical Churches in Azerbaijan and the government is the ‘Israeli factor.’ Israel is seen as one of the principle strategic partners of Azerbaijan, being the third largest trading partner and aiding the government in an effort to diversify the country’s economy7. But what is even more important the Jewish diaspora in the US occupies the central position lobbying for the interests of Azerbaijan. Given the nature of the special relationship between the evangelical community and state of Israel and Jews (Smith 1999), it is not accidental that a few delegations dispatched from the US included the variety of evangelical pastors under the leadership of American Rabbi. So, the lobbying for the interests of the Azerbaijani state in the US, in turn, resulted in the promotion of the interests of local evangelical communities within the state institutions (Batrawy 2019).

Figure 4. Different editions of the Bible published by Azerbaijan Bible Society. © Yulia Aliyeva, 2019.

Paradoxically, the improved relationship between the government and the NTCCs can also be attributed to the successful implementation of restrictive state policies, which certainly contributed to the marginal success of the NTCCs in terms of winning ground and attracting adherents. The official numbers for the registered Evangelical communities claim that the total number of adherents is about 6,100-6,300 (Alizadeh 2018). Pastor Ramiz Khalilov considers that while the number of evangelical churches has increased, the number of the followers has remained relatively the same. According to his estimates, the number of converts from the 90s consisted of 2,500-3,000 individuals, which added to the existing number of Protestants. The total made up no more than 10,000 worshippers, which is quite a moderate result for Azerbaijan’s population of ten million.

Pastor E. noticed that the number of converts could have been much higher, if the communities were not forced to continue their operations within the government framework of ‘strict regulations and control.’ According to him, the ban on proselytizing, the social stigmatization of the converts, combined with the official and unofficial surveillance by the government, restricts the growth of the NTCCs. He also pointed to the gender factor, as women tend to make the decision about conversion more easily than men, and make up most of the worshipper in the churches. For men, such decisions are more challenging, which can be explained by their higher social status, greater inclusion in public life and the fear of damaging their reputation or maybe even be ostracized by colleagues or friends. The pastor deliberated that such decisions do not cause such serious consequences for women, and they are generally tolerated by their families; family members are happy that women do the ‘prayer job’ for the whole family and acquire the new social network, which also may entail familial benefits. Still, there might be some women who attend church services in secret from their husbands, but it is not common.

Pastor A. noticed that a number of the parishioners in the Charismatic and neo-Charismatic religious communities is growing, especially among the youth, but slowly. In general, all interviewed pastors stressed that the goal of the NTCCs is not to race for dramatic growth of their churches, but to welcome and embrace all who are seek the “Word of God”. Given the ban on proselytizing or, as worshippers call it ‘the practice of ‘evangelichit’ (евангеличaть), new members get to know their communities via personal networks, when the adherents spread message in close circles of relatives and friends, usually sharing testimonies of how their life has changed following the conversion.

Informants often indicated that the language of worship was one of the key factors when making their decision in favour of one of the NTCCs. The divide of the population to Russian and Azerbaijani speaking groups is a very sensitive issue in Azerbaijan, often associated with the post-colonial heritage and maintenance of the strong cultural and economic ties with neighboring Russia. Russian language curriculum continues to be popular among various ethnic groups, not only of Slavic origin, as it is believed that education in Russian language provides with better academic knowledge and professional opportunities in the future8. The language issue is more apparent in Baku rather than in more homogeneous communities outside of the metropole. This profound divide of the urban population to Russian-speaking and Azerbaijani-speaking groups impacts the internal organization of the churches. For instance, Adventists, Baptists and Lutherans have two separate groups worshiping every Sunday: the Russian division is for primarily Russian-speakers and the Azerbaijani division is for Azerbaijani-speaking groups. What is interesting is that these language groups have no or very limited interactions with each other and they often unite people belonging to different social categories. For instance, the parish of the Russian division is represented mainly by the elder generation, primarily of women, of ethnically mixed or Slavic origin, whereas the parish of the Azerbaijani division brings together younger people, primarily ethnically Azerbaijanis. In Charismatic churches, the approach is more inclusive, as the worship is conducted in both languages, Russian and Azerbaijani, with simultaneous translation of speeches and songs.

Having the Russian language as the medium of communication facilitates the inclusion of the local NTCCs into the post-soviet networks of evangelical churches. However, many informants stressed the increasing influence of the Turkish evangelical communities, which organize regular exchange visits and broadcast Christian channel in Turkish language in Azerbaijan9 and sometimes invite local pastors as guest-speakers. The increased use of English language opened up the possibility for many religious leaders and regular community members to receive their religious education in Western Europe (for example, in Norway, Sweden and Austria) or in the US. So, the bilingual and multi-lingual parishioners can benefit from the broader geographical engagements.

In this sub-chapter I tried to demonstrate how the relationships between the government and the NTCCs has changed over the last twenty years, and has been informed by changes in the country’s internal strategy; work with religious communities and foreign strategy aimed to promote Azerbaijan as “a showcase for religious tolerance in the Islamic world, and beyond” (Bedford and Souleimanov 2016: 6). The ‘loosening’ of government regulations helped some of the NTCCs acquire ‘official status’ through registration and develop ‘survival strategies’ by building relationships of trust and mutual benefit with the authorities. The key prerequisites for operations of the NTCCs in Azerbaijan thus include two factors: loyalty to the current political regime and withdrawal from open proselytism, especially among Muslims. At the same time, not all NTCCs are included in this ‘positive process,’ as some communities, especially those located outside of the big urban areas, such as Baku, are still striving for recognition and registration, restrained either by the strict regulations or negative attitudes of the local communities.

Evangelical Patriotism

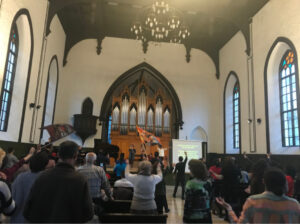

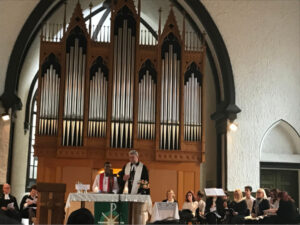

The NTCCs are often described in academic literature as transnational social spaces beyond normatively defined ethnic or national communities, engaged in production of the transgressive cultural constructs. By participating in the NTCC, a convert joins this transnational space and acquires a hybrid, transnational identity, similar to the experiences of the migrants (Levitt and Schiller 2004). This “in-betweenness” extends her networks beyond the local group into the transnational community, acknowledging the existence of brothers and sisters in myriad of global localities and faith gurus of various nationalities. Although the dynamics of religious life varies for each individual along with one’s involvement in transnational ties, the converts’ novel experiences transform their ‘habitus’ – their identity and typical social interaction patterns (Bourdieu 1991). The changes also involve transformation of the practices of consumption of religion and the ‘religious’ as translocal experiences without any engagement in physical mobility. It no longer limits itself to individual spiritual engagements but involves constant exposure to the transnational encounters by hosting the presenters from across the globe, participation in the international meetings and gatherings, study abroad, not to mention the use of congregation’s social media, radio and TV channels. During one of the gatherings of the Seventh Day Adventist Church in Baku the community was called to fundraise for the needs of the Adventist radio located in Ethiopia; in March 2019, women from a number of Protestant communities based in Baku came together to celebrate Women’s World Day of Prayer worshipping for their sisters from Slovenia; in the Vineyard Church an ensemble of Korean girls were dancing a national dance praising Jesus followed by the Ukrainian pastor’s sermon, in which he shared his story of finding faith in Jesus; in the Lutheran church, the choir from Georgia was singing psalms jointly with local parishioners and pastors from Germany and Pakistan. These are just a few examples of the transnational experiences, which I witnessed during a few months of fieldwork. These remarkable global encounters are ultimately present in all NTCCs, enriching the local patterns with supranational meanings and fostering the common mission of sharing the Gospel and helping others to attain ‘salvation.’ As Orlando Woods (2012: 203) argues, evangelical groups “transcend the boundaries imposed by the state and enforced by indigenous religious groups, as they actively seek to baptize people into a trans-ethnic, trans-territorial faith community”. All these trans-territorial communities obviously have ‘centralized’ localities based outside of Azerbaijan, in Western countries, bringing a new sense to the ‘extended habitus’ of being westernized, thus modernized and progressive.

Figure 5. Worship of the Evangelical-Lutheran Congregation in Baku, the Church of the Saviour. Pastors from Germany and Pakistan and choir from Georgia. © Yulia Aliyeva, 2019.

What is peculiar to Azerbaijani NTCCs, though, is its ‘localization’ through the expression of patriotism which is particularity apparent in neo-Pentecostal Churches. Whereas other scholars notice that in other post-Soviet locations they have found “very few references to ethnicity and nationality” (Lankauskas, 2009) in charismatic Christianity communities or the fact that “evangelicalism begins to overshadow, but not necessarily reject the importance of previously invested in other forms of identity, such as nationality” (Wanner 2009), the Azerbaijani representatives of the Christian communities tend to continue active engagement with their national identity, stressing the importance of the sense of nationhood and a sense of belonging to it.

The state-promoted ideology of civic nationalism, defined by citizenship regardless of ethnicity, language or religion, and united in attachment to the state has been the central policy of the government since Azerbaijan gained independence in 1992 (Siroky and Mahmudlu 2016). Although the inclusivity of the ‘civic nationhood’ in Azerbaijan is often questioned because of application of certain restrictive practices incompatible with the liberal-democratic norms, this ideological stance operates in the interests of the NTCCs allowing them to get situated and justify their presence in Azerbaijan.

Based on data collected during my fieldwork in Baku, I argue that the ideology of civic nationalism is widely shared by the members of NTCCs. The process of post-Soviet nation-building in Azerbaijan was coeval with establishment and development of these communities. The widely discussed ability of the NTCCs to adapt and accommodate to the shifts in economic, political, and other societal structures became an important factor which allowed them not only to build ground for new religious orientations, but also to incorporate and share with the local communities the ‘imaginary of a new nation.’ The central idea that the membership in transnational faith communities does not preclude, but even strengthens one’s patriotic spirit and devotion and care for motherland allows for redefinition of identity and accommodation of its fragments. This ‘hybridized identity’ can be regarded as one of the ‘coping strategies’ for these communities, which allows for contextualizing of their new experiences acquired with conversion to evangelical Christianity. At the same time, it serves as a ground for negotiations with the host communities and the state towards greater acceptance and accommodation.

The shifts in the ideological stances of ‘Azerbaijani civic patriotism’ also contributed to the changes in political rationale, opening wider space for negotiation and cooperation between the state and evangelical communities. The first attempt of construction of the post-Soviet national ideology was named ‘Azerbaijanism’ – an overarching identity that includes all citizens, regardless of ethnicity or religion, still emphasizing Azerbaijanis as the titular ethnic group and the unifying dominant culture (Siroky and Mahmudlu 2016). With the launch of the politics of ‘Multiculturalism,’ the government policy took a more inclusive turn, stressing the historical legacy of peaceful co-existence of different ethnic groups and celebrating the religious diversity in Azerbaijan.10 As discussed by Laurence Broers and Ceyhun Mahmudlu, the foundation of this civic Azerbaijan identity is grounded on three major pillars: loyalty to the current political regime (Aliyev’s dynasty); the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and national trauma associated with it; benefits from being a petro-nation; (Broers and Mahmudlu, forthcoming). All these pillars, to a various extent, can be observed across these evangelical groups in the form of the pastor’s address to the parishioners invoking the loyalty to country leadership; prayers for resolution of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and organization of the humanitarian assistance to people who have been affected by the military clashes; some of the communities are the recipients of the annual donations allocated from the Presidential Fund ,thus, getting their small piece of the ‘petro-dollar’ pie.

Moreover, NTCCs are actively engaged in the promotion of ‘civic nationalism’ within the communities through the practices of ‘everyday nationalism.’ As defined by E. Knott (2016: 1), the ‘everyday nationalism’ approach focuses on “ordinary people, as opposed to elites, as the co-constituents, participants and consumers of national symbols, rituals and identities” (1). This form of nationalism does not always follow the institutional pathway but emerges as incidents of mindful or unaware articulations of belonging and caring for one’s nation. Drawing on the existent literature on the subject, Fox and Ginderachter sum up that this version of the nation is narrated in identity talk, implicated in consumption practices, and performed in ritual practices (Fox and Van Ginderachter 2018).

When discussing the NTCCs, one needs to acknowledge the diversity of the cultural forms and logical frameworks of ‘everyday nationalism’ across the congregations, as well as the plurality of ethnic and social backgrounds of the converts, which has to be addressed by Church leadership in their attempts to make the communities inclusive and multicultural. I will discuss some elements below of ‘everyday nationalism’ encountered during my fieldwork, such as identity talks, redefining what does it mean to be a Christian in Azerbaijan; the moral obligation of the parish to engage in ‘prayers for Azerbaijan’ and care for all Azerbaijani people, regardless of their denomination and finally display of the ‘patriotic spirit’ through the prayers for resolution of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

The NTCCs generally position themselves as ‘apolitical’ structures, not engaged in the political processes or striving for political offices. The religious rhetoric employed by the NTCCs also do not differ from the master narrative of other ‘officially approved,’ ‘traditional’ religious groups when it comes to the attitudes to gay-marriages or women’s status in the society. The adherence to patriarchal values were often stressed during the sermons I attended on numerous occasions in various NTCCs, sometimes even praising the Azerbaijani authorities for their ‘right vision,’ while criticizing Western counterparts for betrayal to the Christian values and allowing same-sex unions. The ‘everyday nationalism’ among Azerbaijani Christians manifests itself in an unconscious invocation of the familiar cultural scripts of ‘being Azerbaijani,’ ‘acting as Azerbaijani’ and following the socially accepted gender scripts. Being Christian and ‘acting as Azerbaijani’ can be visually observed during the performances in charismatic Churches, when men usually prefer motionless standing on their feet in the last rows of the hall, whereas women feel more relaxed expressing themselves in ecstatic bodily movements. This tense performance, if asked directly, is explained by being ‘Azerbaijani men.’ For men, showing sentiments and lively performances in public still considered a strong social and internal taboo addressed in the common saying “Kişi ağır olar” – ‘Man should be tough,’ which comes at odds with the joyful and inviting atmosphere of Charismatic worship. This code, though, is violated by Church leadership, predominantly men, showcasing an interesting contrast between the male adherents and ‘community activists.’ These are the males who are closely engaged in the ‘shaping of the religious community’, received a religious training abroad, or, in other words, have a ‘special status,’ allowing them to redefine ‘masculinity.’ Some of these activist male worshippers are also coming from artistic professions, implying stage performances, what supposedly makes the violation of the code and display of the emotions in public easier for them.

Engagement with the ‘real Azerbaijani men,’ as some of the converts approached by me identified themselves, involved conversations about the nature of male and female interactions and the standards of ‘decent behavior’ in encounters with the opposite gender. The assumptions were not much different from the patriarchal codes accepted in conservative circles and, for instance, included questioning the nature of my work, which requires the arrangement of the interviews, or otherwise face-to-face meetings, with male strangers.

As discussed in academic literature, the success of the NTCCs, notably in Pentecostal communities, in gaining solid ground around the world is also attributed to creative appropriation of local cultural values and practices (Robbins 2004). As Catherine Wanner (2006) rightly puts it: “Religious practice is grounded in a particular place, even as it transcends it” (14). Thus, the social milieu impacts the way Christian identity is constructed and defined in line with the social expectations of what is pious and morally grounded spiritual life. The comparison with the local traditional religious groups, specifically Muslim communities, were constantly raised by the adherents to demonstrate how they ‘fit’ to the general social fabric, how their moral code and religious practices are in line and not ‘contra’ with the mainstream religions. On the other hand, they were noting the non-militant character of the local Islam, being “the most tolerant Islam in the world,” which shows respect and even love to Saint Mary and Jesus (Invictory 2008).

In conversation, the converts often tried to invalidate their “Otherness” by pointing to similarities with the ‘host group.’ The Christian values, associated with the value of familial networks, mutual support and solidarity, are seen as being in line with ‘the Azerbaijani way of life,’ whereas the withdrawal from consumption of alcohol and tobacco, ban on strong language and promiscuity are regarded as corresponding with the Muslim doctrine. The conversion thus involves creative ways of validating one’s personal faith choice and the production of narratives affirming one’s sense of belonging through acquisition of the hybrid identity.

This involves ‘identity talks,’ representing not just articulation of the one’s perceived identity, but also an attempt to present publicly acceptable narratives. For instance, here is how Pastor R. describes how he comprehends his identity:

“I am a Christian; this is definitely to the bone. But I am also Azerbaijani. To the marrow of my bones as well. As we discussed the Jesus was 100% God and 100% human, 100% iron and 100% flame, so I am 100% Christian and 100% Azerbaijani.”

In a discussion, the pastor recalled the conversation of one woman who challenged his claim that Jesus was 100% God and 100% human: she claimed it was mathematically invalid. Later, his mentor in one of the Western churches resolved this theorem by bringing an analogy with iron which is put into the flame, where it turns red, but does not stop being iron but incorporates the heat of the flame, thus creating an incandescent identity, making it firm and inseparable. This analogy not only validated the existence and possibility of ‘hybridity,’ but also proved it to be a special, ‘divine arrangement.’

Quite often, pastors were claimed to be more knowledgeable of the Muslim tradition, accusing the locals of being ignorantly against the NTCCs. Here is the one of the examples of downplaying the Muslim identity in locals:

“Azerbaijanis themselves, according to statistics, 95-96% consider themselves Muslims, but I do not consider them. Why, because only 10% actually perform the requirements of Islam. But the rest… they don’t do anything, there are those who only fast during fasting, they are not Muslims. They don’t even know what “Kəlmeyi-şəhadə” is. I teach them. I myself, a pastor in Christianity, but I teach them Kəlmeyi-şəhadət. I say, how do you consider yourself a Muslim?… Our people think that after the circumcision is done to the boys, that’s all, they are Muslims.”

Another pastor was confronting the fellowmen with discussion that the Muslim faith which is not supported by the reading of the religious texts and observance of the rituals resembles ash:

“What is ash? When you take it, it disappears. You want to hold it in your hand but there is nothing left. But faith is the fruit of the relationship, when we have relationships, when we are becoming friends, walk together, do business or anything else, it is here when when our relationships begin to emerge

There are two central narratives when pastors discuss the relationship between the NTCCs with host communities. The first discusses people in Azerbaijan as ‘faithless,’ disoriented and ignorant. Moreover, they are firmly ‘stuck’ in ‘ethnodoxy,’ or a belief that religion is ascribed at birth, which often makes them irresponsive and resistant to the teachings of Christianity. The second point is concerned with the lack of bonding values and cohesion in society. By contrasting the community of Christians where faith is the ‘fruit of relationships’ not only with Divine forces but also with community members, supporting each other and striving together towards prosperity. So, ‘ash,’ the religious identity without faith, is considered to be one of the biggest challenges and problems for post-Soviet Azerbaijan.

At least three of the interviewed pastors confessed to having a ‘Muslim’ phase in their lives, when they were actively practicing Islam, doing namaz (daily prayers) and regularly attending mosques. The knowledge accumulated during that period helps them now when they engage with ‘culturally Muslims,’ as they are aware of the both Quranic and Bible teachings and can lead well-informed debates pointing to similarities and differences in religious discourses. The engagement in such conversations with local populations helps them to re-construct and expand the ‘official’ meanings of nationalism and nationhood in routine practices. For instance, one of the pastors who was previously involved in criminal activities and heavy alcoholism, considers that his personal example is the best testimony of the almighty God, which he is not shy to share on numerous occasions in tea houses and social gatherings (majlis), including the morning ceremonies lead by mullahs. One of the first challenges for him is to persuade people that “Jesus is not Russian”11 and that Azerbaijanis can also join this religion without compromising their personal relations or values system, but instead can acquire a solid standpoint for renewed and more mindful spiritual life.

Figure 6. Symbolic of the Azerbaijan Republic (national emblem) represented at the facade of the Church of the Saviour following its reconstruction in 2001. © Yulia Aliyeva, 2019.

There are also very small and generally quiet attempts to reconsider the status of Islam in Azerbaijan, which may potentially have negative implications in relationship with the authorities, as challenging the ‘foundations of national identity.’ For instance, Pastor Z pointed out that the Christian history of Azerbaijan is not adequately addressed in the school history textbook, as it does not provide a detailed account about the local resistance to Arab conquest and forceful Islamization. So, the Muslim identity within such discourse appears to be ‘alien’, enforced from above, in contrast to the Christian faith, voluntarily embraced by Caucasian Albania – one of the predecessors of the modern Azerbaijan.

The second pattern includes manifestations of the ‘everyday nationalism’ though the script of belonging and careering for the future of the country. Most commonly it is exhibited by the leadership of the churches in the sermons which include musical performances praising Azerbaijan, the prayers for its bright future and prosperity, including the requests for higher pensions, stable economy, eradication of poverty in the country and expression of gratitude to the leadership of the country for their benevolence. On one occasion, while congratulating the President of Azerbaijan on his birthday, one of the Pastors concluded that the fact that Ilham Aliyev was born on December 24th may not be an accident but a divine arrangement. This display of loyalty to the regime also includes participation of the representatives of the registered communities in the various events in Azerbaijan and abroad, aimed to demonstrate the politics of tolerance in the country.

I have also witnessed how some of the churches merged religious and national symbolism, producing a hybrid representation. Quite often these are visual images of biblical verses written over the map of Azerbaijan, with the slogan ‘God Loves Azerbaijan’ on a panoramic picture of Baku or on the national flag with an emblem of Christian society, such as on the logo of the Azerbaijan Bible Institute. This hybridity also manifests itself in the celebration of national, secular holidays in the churches. Almost all churches, for instance, celebrate Women’s Day on the eighth of March, the Soviet holiday, by addressing women with the special sermons and prayers, staging the performances for them, mostly engaging kids, and by opening festive tables. In one of the churches, I participated in the celebration of National Flag Day on November ninth, when the national flag of Azerbaijan (visually bigger than flags with Christian symbols) was placed into the center of celebrations, and under the Christian hymns the worshippers were actively waving flags. The performances on that day also included national dances and songs based on national music traditions praising Jesus.

Less perceptibly, discussions about love, the future of Azerbaijani people that are lost in transitions and left without ‘moral orientations’ are a common part of the internal discourses within the communities. For instance, one Adventist woman, during the Bible readings by the small ‘cells,’ (groups) was sharing her emotions on how painful it is for her to recognize that her valued colleagues at work, who are not Christians, will suffer enormous pain in the times of the Apocalypse:

“Sometime when I look at them, I imagine the sores and wounds on their skin and I want to cry. Please pray for me to find the strength to help them avoid this horrible fate.”

In some churches, special days and hours are dedicated to the prayers for “awakening of Azerbaijan.”12 In one of the churches, these are usually intense musical performances asking God to extend His grace to Azerbaijan, send wisdom to the country’s leadership, and to strengthen believers and fortify their faith. In such prayers, not only the church leadership but also parishioners make contributions to the prayer, singing or reciting verses and standing on foot or on their knees in a circle. Of course, the ultimate goal of these prayers, although not openly declared, is salvation of Azerbaijan through its evangelization. At the same time, the prayers are ‘inclusive,’ wishing good to all people and all communities living on this territory.

Serving in Azerbaijan, being part of the mundane and religious life in the country is defined as a divine opportunity, manifestation of love and care of God for Azerbaijan. Here is an account by one of the pastors on how he was persuaded by his mentor to return to Azerbaijan and start his service there after living for some abroad:

“God is an amazing God, who gives us a choice in everything. It is an amazing gift he gave a person – the opportunity to choose what to drink, where to go, which lifestyle to lead. Believe or not to believe, kill or not to kill. We cannot make a choice of just two things.” For me it was something new. I have never heard anything like this… He continued: ‘It is who you will be born: a man or a woman. And secondly, where will you be born. These are two things you do not choose… and so God has a perfect plan for you, for your people, in your nation. I am sure that that God will work with you in Azerbaijan. Go, son, go…”

The major emphasis in this script are assigned to the necessity of serving one’s own people and nation, even by making a personal sacrifice and giving up the familiar lifestyle. The personal ambitions and aspirations are then given marginal prominence in light of the necessity to act as an emancipator in one’s own nation.

Contrary to this intimate personal account of how one justifies his position in leading an ‘alien’ religious cult, ‘the everyday nationalism’ can manifest itself in overt expression of the Church’s support of the national interests. This can be best illustrated by the case from the World of Life Church, which starting in 2012 and included in its regular sermons the prayer for Karabakh (Alizadeh 2018). As Rasim Khalilov, the pastor of the church at that time explained, he was touched by the negative developments at the border and appealed to the congregation to do the prayer for Karabakh and return of the occupied territories. The sermon was audio recorded and posted online, raising a wave of discontent in Armenia and what was reported to Khalilov through fellow-congregations located in other countries. But he addressed the critics by evoking the obligation of every Christian to pray for her land: “I prayed for my land, you pray for your land. That’s how it all ended…”

This case illustrates the situation when the ethno-nationalism comes into conflict with the supra-national ties and importance of the unity within the transnational religious community. The grounded religious practices, along with a skillful adaptation to the dynamics of the political life in Azerbaijan put forth the necessity to outline one’s political stance to provide legitimacy for the community. The patriotic narrative along with the expression of one’s Azerbaijani identity become the validation of the hybrid identity or re-defined national identity compatible with Christianity. This move also provided credits to the World of Life church as loyal to the general doctrine of the government and further inclusion of the community to the list of ‘loyal religious circles’ which are invited to take the sit at the table along with the ‘traditional communities.’

Thus, the evangelical communities in Baku portray an interesting interplay of transnational and local forces, intersecting and hybrid identities, thus creating “cross-cutting cleavages,” defined by Baumann as communities which do not run parallel but rather cut across one another to form an ever-changing pattern (Baumann 2010: 84). Being Azerbaijani and being evangelical Christian signifies the possibility of making a choice in personal spiritual life, but it also implies the struggle for recognition and acceptance. The engagement in ‘everyday nationalism’ hence becomes the important coping strategy in quest for acceptance connoting belonging and loyalty.

Conclusion

The case of NTCC in Azerbaijan offers a new insight into the interplay of secularism, religion and modernity in the urban environment. The post-Soviet environment opened new opportunities for the development of the NTCCs in Azerbaijan, contributing to the increasing diversity of worship and formation of the new trans-localized identities. The Azerbaijani doctrine of civic nationhood asserts the establishment of the national unity through the promotion of civic equality and multicultural harmony. Although the implementation of this policy has not been always linear and ‘inclusive,’ it allowed for establishment and operation of the NTCCs in the post-Soviet republic. The ideology of ‘Multiculturalism’ and development of the mutually beneficial frameworks for cooperation allowed the NTCCs to secure the more stable position and government’s endorsement for operations. The existing plurality of the NTCCs and their presence in the symbolic historical sights signifies to the members of these communities the gradual change in government’s attitudes and lessens a fear for any negative consequences because of the conversion.

At the same time, the NTCCs operate in an environment which can be defined as structurally hostile. The major sources of these hostilities are the strict regulations and close surveillance policies targeting all religious communities, not only for the NTCCs, and the widely shared by general public belief in ‘ethnodoxy’, that the religious faith is ascribed rather than acquired identity. These two aspects pose a critical challenge for development of the communities, but also teach them how to skillfully navigate the local environment and negotiate the restrictions. One of these ‘coping strategies’ is the promotion of ‘everyday nationalism’ in the communities, which signifies itself through the narratives of belonging to the nation and solidarity with the fellow country-men when it comes to the developments critical for the nationhood and loyalty to the current political regime as guarantor of the peaceful co-existence with the host-communities and uninterrupted operations for NTCCs.

Note on the Author

Yuliya Aliyeva (Gureyeva) is an Instructor in Social Sciences, SPIA, ADA University. From 2007- 2014 she worked for the Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC-Azerbaijan) managing various data collections and research projects, including the Caucasus Barometer. Her areas of interest include study of religious communities, social and institutional discourses of gender, and social cohesion. Email: yaliyeva@ada.edu.az

References

AITAMURTO K. 2016. “Protected and Controlled. Islam and ‘Desecularisation from Above’ in Russia” Europe-Asia Studies 68(1), 182-202.

ALIZADEH, A. 2018. Christianity In Azerbaijan: From Past to Present. Baku: Sherq-Qerb Publishing House.

BASHIROV, G. 2018. “Islamic discourses in Azerbaijan: the securitization of ‘non-traditional religious movements’”. Central Asian Survey 37(1): 31-49.

BATRAWY, A. 2019. “Rabbi leads US evangelicals in visit to Muslim Azerbaijan”. Washington Times. March 7, 2019. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2019/mar/7/rabbi-leads-us-evangelicals-in-visit-to-muslim-aze/.

BAUMANN, G. 2010. The multicultural riddle: Rethinking national, ethnic, and religious identities. New York: Routledge.

BEDFORD S. and SOULEIMANOV E.A. 2016. “Under construction and highly contested: Islam in the post-Soviet Caucasus”. Third World Quarterly 37(9): 1559-1580.

BOURDIEU, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Trans. Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

BROERS, L. and MAHMUDLU, C. (Forthcoming). “Civic Dominion: Nation-Building in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan”. P. Rutland, ed. Nations and States in the Post-Soviet Space. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CORNELL, S. 2011. Azerbaijan Since Independence. New York: Routledge.

CORNELL, S. E., KARAVELI H. M. and AJEGANOV B. 2016. “Azerbaijan’s Formula: Secular Governance and Civic Nationhood”. Silk Road Paper, November 23, 2016.

ERGUN, A. and ÇITAK, Z. 2020. “Secularism and National Identity in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan”. Journal of Church and State 62(3): 464-485.

FOX, J. and VAN GINDERACHTER, M. 2018. “Introduction: Everyday nationalism‘s evidence problem”. Nations and Nationalism 24: 546-552.

GOYUSHOV, A. 2008. “Islamic Revival in Azerbaijan”. Current Trends in Islamist Ideology 7. Hudson Institute. https://www.hudson.org/research/9815-islamic-revival-in-azerbaijan.

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 2016. Azerbaijan: compulsory military service, including requirements and exemptions; penalties for evasion or desertion (2011-May 2016), 2 June, AZE105538.E. https://www.refworld.org/docid/57974d494.html.

KARPOV, V., LISOVSKAYA, E. and BARRY, D. 2012. “Ethnodoxy: How Popular Ideologies Fuse Religious and Ethnic Identities”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51(4): 638-655.

KNOTT, E. 2016. ‘Everyday nationalism. A review of the literature’, Studies on National Movements 3. http://snm.nise.eu/index.php/studies/article/view/0308s.

LANKAUSKAS, G. 2009. “The Civility and Pragmatism of Charismatic Christianity in Lithuania”. In: M. Pelkmans ed. Conversion After Socialism. Disruptions, Modernisms and Technologies of Faith in the Former Soviet Union. Berghahn Books.

LEHMANN, D. 2013. “Religion as Heritage, Religion as Belief: Shifting Frontiers of Secularism in Europe, the USA and Brazil.” International Sociology 28(6): 645-62.

LEVITT, P. and SCHILLER, N. G. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society”. International Migration Review, 38(3): 1002-1039.

NURUZADE, S. 2016. “Religious Views in Modern Azerbaijan”. J Socialomics 5:187 doi:10.41 72/2167-0358.1000187.

OPEN DOORS. 2018. Keys to understanding Azerbaijan. https://www.opendoors.no/Admin/Public/Download.aspx?file=Files%2FFiles%2FNO%2FWWL-2018-dokumenter%2FAzerbaijan-Keys-to-Understanding.pdf.

PEEL, J.D.Y. 2009. “Postsocialism, Postcolonialism, Pentecostalism”. In: M. Pelkmans ed. Conversion After Socialism. Disruptions, Modernisms and Technologies of Faith in the Former Soviet Union. Berghahn Books.

RAČIUS, E. 2020. “The legal notion of “traditional” religions in Lithuania and its sociopolitical consequences”. Journal of Law and Religion 35(1), 61-78.

ROBBINS, J. 2004. “The Globalization of Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity”. Annual Review of Anthropology 33: 117-143.

SADIQOV, V. 2017. “Azerbaijan: A living example of unity in diversity”. In Focus 2 (the UNESCO International Bureau of Education (IBE): 108-117 https://ibe-infocus.org/articles/azerbaijan-living-example-unity-diversity/.

ȘANCARIUC, R. 2017. “Cultural Diversity: Same Question, but a Different Answer. The Story of Azerbaijani Multiculturalism.” The Market of Ideas 4. http://www.themarketforideas.com/cultural-diversity-same-question-but-a-different-answerthe-story-of-azerbaijani-multiculturalism-a222/.

SHIRIYEV Z. 2017. Betwixt and Between: The Reality of Russian Soft-Power in Azerbaijan. https://ge.boell.org/en/2017/10/16/betwixt-and-between-reality-russian-soft-power-azerbaijanon.

SIROKY D. S. and MAHMUDLU C. 2016. “E Pluribus Unum? Ethnicity, Islam, and the Construction of Identity in Azerbaijan”. Problems of Post-Communism 63(2): 94-107.

SMITH, T.W. 1999. “The Religious Right and Anti-Semitism.” Review of Religious Research 40 (3): 244-258.

STILO, A. 2017. “Is Multiculturalism in Azerbaijan a Valuable Model?”. Europeinfos newsletter # 207. November 2017. http://www.europe-infos.eu/is-multiculturalism-in-azerbaijan-a-valuable-model.

VALIYEV, A. 2008. “Foreign Terrorist Groups and Rise of Home‐grown Radicalism in Azerbaijan”. Journal of Human Security 2: 92-112.

WANNER, C. 2009. “Conversion and the Mobile Self: Evangelicalism as ‘Travelling Culture”. In: M. Pelkmans ed. Conversion After Socialism. Disruptions, Modernisms and Technologies of Faith in the Former Soviet Union. Berghahn Books.

WANNER, C. 2006. “Evangelicalism and The Resurgence of Religion in Ukraine.” NCEEER Working Papers. February 15, 2006. 21 pp.

WIKTOR-MACH, D. 2017. Religious Revival and Secularism in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

WOODS, O. 2012. “Sri Lanka‘s informal religious economy: Evangelical competitiveness and Buddhist hegemony in perspective”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51(2): 203-219.

Sources in Russian and Azerbaijani

ABDULLAYEVA, F. 2013. “Azerbaijan is a place where different religious confessions live in tolerance” (Azərbaycan müxtəlif dini konfessiyaların tolerantlıq şəraitində yaşadığı məkandır). Medeniyyet.az. August 3, 2013. http://medeniyyet.az/page/news/18329/Azerbaycan-muxtelif-dini-konfessiyalarin-tolerantliq-seraitinde-yasadigi-mekandir.html.

ALEKPEROVA, J. 2017. “Azerbaijan urged to start dealing closely with Jehovah‘s Witnesses” (В Азербайджане предложили вплотную заняться “иеговистами”). Echo.az. April 17, 2017. https://ru.echo.az/?p=58501.

BİNGÖL, N. 2018. “We will work with the victims of fanaticism and radicalism” – Interview with the Deputy Chairman of the Religious Committee” (Fanatizm və radikalizmə məruz qalanlarla iş aparılacaq – Dini Komitənin sədr müavini ilə müsahibə). MODERN.AZ, January 23, 2018. https://modern.az/az/news/154984.

HASANLI, J. 2018. Soviet Liberalism in Azerbaijan: Government, Intelligentsia, People (1959-1969) (Azərbaycanda Sovet liberalizmi: Hakimiyyət. ziyalılar. Xalq. (1959-1969). Baku: Ganun Publishing (QANUN nəşriyyatı).

INVICTORY. 2008. Web conference with Pastor of ‘Word of Life’ in Azerbaijan (Веб-конференция с пастором „Слово Жизни“ в Азербайджане). October 26, 2008. http://www.invictory.com/news/story-18314-%D0%A0%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%BC-%D0%A5%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B2.html.

MEDIATV.AZ. 2015. Friendship with enemy and evasion from military service (Düşmənlə dostluq, hərbi xidmətdən yayınma). April 9, 2015 http://mediatv.az/karusel/13100-dushmenle-dostluq-herbi-xidmetden-yayinma.html.

MEHDIYEV, R. 2005. Azərbaycan: qloballaşma dövrünün tələbləri. (Azerbaijan: Demands of the Era of Globalization). Baku: “XXI – Yeni Nəşrlər Evi“ (“XXI – New Publishing House”).

MILLI MAJLIS, Stenogram. 2011. The speech of S.Hasanli, Deputy of the Leader of Caucasus Muslim Board. Protocol 18. June 10, 2011. https://www.meclis.gov.az/?/az/stenoqram/259.

SALAMNEWS. 2018. Presentation about Azerbaijan hold in OCSE (В ОБСЕ проведена презентация об Азербайджане). September 15, 2018. https://www.salamnews.org/ru/news/read/322497.

New Diversities • Volume 23, No. 2, 2021

Special issue: Urban Religious Pluralization: Challenges and Opportunities in the post-Soviet South Caucasus

Guest Editors: Tsypylma Darieva (Centre for East European and international Studies) and Julie McBrien (University of Amsterdam)

- ISSN-Print 2199-8108

- ISSN-Internet 2199-8116

- This research is part of the wider study “Transformation of urban spaces and religious pluralisation in the Caucasus” funded by the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) (https://en.zois-berlin.de/research/research-areas/transformation-of-urban-spaces-and-religious-pluralisation-in-the-caucasus/).

- According to recent data published on the website of the State Committee on Religious Associations of the Republic of Azerbaijan, there are 941 religious communities registered in Azerbaijan since 2009 to-date, 906 of which are Muslim communities, twenty-four are Christian, eight are Jewish, one is Krishna and two are Baha’i. There are fourteen churches and seven synagogues in Azerbaijan (http://www.dqdk.gov.az/az/view/pages/306?menu_id=83); Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan - Presidential Library - Religion (Date not specified) http://files.preslib.az/projects/remz/pdf_en/atr_din.pdf

- All communities included to the fieldwork are registered with the State Committee on Religious Associations of the Republic of Azerbaijan (SCWRA). Attempts to establish contact with unregistered Christian groups located in Baku were unsuccessful as the community leaders refused to be interviewed. A leader of the unregistered religious community located in one of the regions of Azerbaijan explained that the community has not filed the registration documents since it has less than fifty adult permanent members, which is the minimum requirement established by law. The worship of this unnregistered group takes place in his private house. At the beginning of his ‘religious career’ as a local community leader he used to have problems with the local authorities and was under close surveillance. But starting in 2013, community members were allowed to gather for regular prayers in his home, which he attributes to his ability to persuade people that his activities are ‘not dangerous’ and, to the contrary, serve to the interests of the community and help to ‘cure’ socially undesirable traits, such as alcoholism and drug abuse and even religious fanatism.

- http://www.scwra.gov.az/ru%20/view/pages/297?menu_id=81

- Based on my interview with Konstantin Kolesnikov, the representative of the Russian Orthodox Church in Baku, January 2019.

- To ensure the privacy and safety of informants, I am using the pseudonyms for the interviewed leaders of the evangelical communities and do not identify churches with which they are affiliated. The only exception is Pastor Rasim Khalilov, Chairman of Azerbaijan Bible Society since he is a well-known public figure and makes constant appearances in the local mass media.

- For more information on diplomacy and policy support of Israel and Jewish lobby to Azerbaijan please see: Ismayilov, M. 2018. “The Changing Landscape of (Political) Islam in Azerbaijan: Its Contextual Underpinnings and Future Prospects. Central Asian Affairs 5(4): 342-372, p. 361; Lindenstrauss, Gallia. 2015. “Israel-Azerbaijan: Despite the Constraints, a Special Relationship”. Strategic Assessment 17 (4), January 2015.

- The number of public Russian-only schools has not significantly changed since 1989; there are sixteen Russian schools in Azerbaijan and 380 schools which offer both Azerbaijani and Russian streams. The number of pupils who choose to study in Russian has been increasing over the last years, especially in Baku (Shiriyev 2017).

- The Azerbaijani language is a part of the Turkic family, which makes Turkish and Azerbaijani very similar, and although there are significant differences, both communities can often understand one another without the need for translation.

- For more information about ‘hybrid’ model uniting the idea of ‘civic nationhood’ and with the ‘multiculturalism’ policy, please, see the discussion in Cornell, S. E., Karaveli H. M. and Ajeganov B. 2016. “Azerbaijan’s Formula: Secular Governance and Civic Nationhood”. Silk Road Paper, November 23, 2016.

- For a discussion about Jesus as the ‘Russian God’ in Siberia and Central Asia see the contributions to the ‘Conversion After Socialism. Disruptions, Modernisms and Technologies of Faith in the Former Soviet Union’, Mathijs Pelkmans ed., 2009, Berghahn Books.

- Such prayers are not always open to the public, as in one of the churches I was not allowed to participate; this was justified as being an ‘internal matter’ of the parish.