New Diversities • Volume 23, No. 2, 2021

Representations of Religious Plurality in the Urban Space of Post-Socialist Rustavi

by Tea Kamushadze (Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University | TSU)

To cite this article: Kamushadze, T. (2021). Representations of Religious Plurality in the Urban Space of Post-Socialist Rustavi. New Diversities, 23(2), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.58002/t7e6-4e68

Abstract: This paper focuses on the urban environment and topography of the religious architecture of the city of Rustavi, which establishes a new hierarchy and order in the former workers‘ city. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a sharp transformation in religiosity across the country, largely due to the construction of new religious sites, the restoration of old buildings and the rebuilding of various sites of worship. Another layer that was revealed after the collapse of the Soviet system was the emergence of new religious groups that competed fiercely and that actively began seeking their place in the post-atheist, post-secular space. The scarcity of resistance to co-existence and the search for forms of it are controversial in the urban setting, where religious symbols, in addition to their sacred significance, possess national and political meanings. Based on my ethnographic fieldwork, I examine different spatial practices and interpretations that frame the co-existence of the mainstream Georgian Orthodox Church, Georgian Catholics and the Muslim community in Rustavi. I argue that the struggle for religious spaces blends with the city’s genesis in the Soviet period, which involved reviving the historic city and endowing it with an international, industrial profile. These two contradictory faces of the city, both created by the communists, are present in religious forms today and enable the search for new identities.

Keywords: Georgia, the city of forty brothers, religious pluralism, religious minority, urban space, diversity, public religiosity, post-socialist Rustavi, national narratives

This research was supported by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia (SRSFG) grant number – YS-19-521.

Introduction

Giga Lortkipanidze1 once said, ‘We have established a theatre, what is a city without a theatre?! But a city cannot be real without a church either!

Yes, we all felt it, but we were silent’

giga lortkipanidzem ertkhel tkva, teat’ri k’i davaarset, is ra kalakia, sadats teat’ri araa! magram arts isaa namdvii kalaki, sadac ek’lesia araa!

diakh, chven q’vela vgrdznobdit amas, magram gachumebuli viq’avit.’ (Mumladze 1991: 5)

Socialist Rustavi was designed as an exemplary city of workers, with no place for sacred sites or religion.2 The communists found a meaningful place for the city, built in an empty space, in the history of Georgia. Soviet urban narratives placed Rustavi at the centre of medieval events in Georgia’s history and turned it into a source of Georgian Soviet nationalism. The connection of the twelfth-century poet Shota Rustaveli with Rustavi became a guarantee of its national significance. At the same time, the multinational population of Rustavi provided a heavy industrial and socialist profile for the city. Those of the city’s national and international images that were suggested by the communists became the basis of opportunities for Rustavians to contemplate building or restoring a church in the city before the collapse of the Soviet Union. Finding a place for churches and crosses in the urban planning of contemporary Rustavi was not difficult. The emergence of Orthodox symbols in the streets and their perceptions are directly linked to interpretations of the city‘s national narrative, which can be conceptualized as rebuilding, restoring or reviving its lost historical realities. Other religious confessions found themselves in different circumstances. Their representation in the urban environment of the city faced certain obstacles, as their experience was not connected with the city‘s historical past. The necessarily mono-religious nature of medieval Rustavi, the revival narrative of which has become even more relevant since the post-socialist period, was its main source of identity. Historical understanding and experience of the plurality of religions and their co-existence simply did not exist (Lomtatidze 1975).

Prominent religious groups in the post-Soviet period were primarily perceived as a threat to religious unity. Rustavi, the economic and social profile of which is linked to the Soviet system, had to prove its significance to Georgian society generally in the post-socialist era. The main method in this case was the construction of Orthodox churches and demonstrations of religiosity. To achieve this, the Orthodox churches commonly resorted to publicity. Members of other religious groups, conversely, found it very difficult to find a place in the city, despite their large experience of multi-ethnic communities and multiculturalism in the recent past, in line with Rustavi being named the City of Forty Brothers and the City of Brotherhood (Kamushadze 2017).3 In the new reality, the challenges posed by religious groups are seen in the controversy surrounding the construction of a Catholic church, which, along with legal barriers, also exposed public intolerance. The fact that the construction of a Catholic church near a public school was perceived as a social threat by the majority of the population also indicates non-recognition of this category of church. Obtaining a permit for its construction became possible only after the proposed location was changed (50-year-old man, 2020).4 The visibility of the city’s Muslim community has also been an insurmountable challenge, leading to its failure to build a Muslim shrine in Rustavi (24-year-old woman, 2019). For other religious groups, the main challenge is still to establish themselves in the city space and to enjoy some form of visibility. As the city’s chief architect explained to me in a private conversation, the only consent granted for the construction of a religious building was in response to the request of the Catholic church. As for non-Orthodox religious buildings owned by other denominations, they were built for other purposes and were then transferred or sold to the representatives of various religious groups. However, any attempt to display religious symbols on buildings provokes protests from the Orthodox population (Architect, 2020). Consequently, the process of their establishment in the urban space is still controversial in Rustavi, permitting different interpretations of the multicultural nature of the city.

The issue of religious diversity in Rustavi is related to the city’s ethnic composition. In the post-Soviet period, this City of Forty Brothers, which was declared a symbol of multiethnic communities and multiculturalism across the country, became a less than convincing Soviet metaphor. According to the 2014 census data, the vast majority of the city‘s population is Georgian (92%), while 4% are Azeris, followed by Armenians and Russians. In addition, the list includes Ossetians, Ukrainians, Kists, Greeks and Assyrians (Geostat 2014). The three cases of religious establishments in the city discussed in this article concern Georgian Orthodox Christians, Georgian Latin Catholics and Georgia’s Azeri Muslim community. By presenting these three cases, I would like to show that ethnic markers play a role in the representation of these groups’ religiosity.

This article discusses the construction of the first Orthodox and therefore first Christian church in Rustavi, which started in the late socialist period. In addition, the article discusses the growing interest in the construction of Orthodox churches in post-Soviet Rustavi and what provoked the process, as well as the importance and role of the Orthodox Church in the urban space of Rustavi more generally. The article also examines what the churches were called and describes the history of those that have already been built or are currently under construction. All of this is inherent in the texture of Rustavi‘s urban narratives. The city’s so-called ‘yard chapels,’ built and funded by neighbourhoods, are also noteworthy in this respect. What is the function of these chapels? How do these issues relate to Rustavi‘s national narrative? I also examine why the international nature of the city was not reflected in its religious plurality. Why is it difficult and sometimes impossible to establish an urban space for some confessions? In this context, the question arises as to why, for five years, Catholic Christians were not allowed to build a church on their own land in Rustavi? What was the basis of this dispute? It is also important to understand which religious groups managed to establish themselves in the urban space of Rustavi and how. The issue of the Muslim community is also noteworthy. Why does this religion lack sites of its own in Rustavi?

Analysing Religious Plurality in Rustavi

Ethnic Georgians, Rustavi’s majority population, are predominantly Orthodox Christian. This is reflected not only in the construction of Orthodox churches in the city but also in the marking of public spaces like so-called yard chapels with other kinds of religious symbols. As noted by Silvia Serrano, in the process of State building, the Orthodox Church in Georgia is actively demarcating territories, interpreting the country‘s past and claiming cultural heritage. Weak state institutions, impoverished political actors and high public trust in the Orthodox Church give the Orthodox clergy a great opportunity to interpret what being a Georgian means (Serrano 2010). The close connection between Georgia and Orthodoxy is also described by Mathijs Pelkmans, who observed the process of the population’s conversion from Islam to Christianity in Adjara, which his interlocutors saw as a way of going back to the roots (Pelkmans 2002). It can be argued that Rustavi is no exception regarding the position of the Orthodox Church. Indeed, my Georgian Catholic interlocutors made observations similar to Pelkmans’s and described their conversion to Orthodoxy as a way of returning to the roots, as they considered Orthodox Christianity an integral part of being Georgian.

Although religions largely originate and spread in cities, it took a long time to recognize their importance in the urban context (Casanova 2013). The revision of concepts related to secularization is also a part of this process. According to the theory of secularization, with the growth of modernity the importance of religion should decline. Developments in the world over the past few decades, including in cities, have revealed a different reality, which has led to the need for a corresponding interpretation and reformulation of theoretical models of secularization. Recognizing ‘multiple modernity’, Peter Berger put forward his own vision of the current situation of religious pluralism and its twofold understanding as first, the co-existence of religious and secular institutions, and second, the existence of common shared spaces for different religious world views (Berger 2014). Berger‘s understanding of religious pluralism fully reflects the reality in Georgia, especially in Rustavi, which also hints at the possibility of conflict in the urban space and the need to create mechanisms to respond to it. In the Document of Strategic Development issued by the State Agency for Religious Affairs of Georgia, the concept of pluralism refers to two situations: first, to the prevention of religious conflict, which is detrimental to pluralism; and second, to the religious minorities that are a vital part of Georgia’s pluralistic society and that contribute to community diversity. In both cases, pluralism is seen as something that needs to be protected (State Agency for Religious Issues 2015). Religious diversity in cities does increase the possibility of conflict, but urban society cannot live in constant conflict. Thus, mechanisms of avoiding, managing and resolving the conflict should be developed in the relevant environment (Berking et al. 2018: 7).

The situation in Rustavi reflects the relationship between religious groups and state institutions, the coexistence and balance of which have so far largely been achieved at the expense of the interests of minorities, which offer different interpretations of religious pluralism at the formal, political and public levels. To discuss the peculiarities of religious competition and religious pluralism in Rustavi, I have chosen the urban space of the city and an expression of religiosity—religious architecture—that creates a discourse of symbolic power with visual characteristics:

‘Objects become icons when they have not only material force but also symbolic power. Actors have iconic consciousness when they experience material objects, not only understanding them cognitively or evaluating them morally but also feeling their sensual, aesthetic force.’ (Knott et al. 2016: 128)

Interest in religious buildings is triggered not only by their salient form and content, but also by their perceptual features, which, together with new practices, create the tools for forming identities and fighting for power. Religious objects become icons that establish a new order and hierarchy in the city. The hierarchy between religious groups is also indicated in their distribution in the urban space. It should be noted that the centre, including from the religious point of view, is New Rustavi, which is more densely populated and separated from Old Rustavi by the Mtkvari River, its construction beginning in the late socialist period, and more specifically in the 1970s. The importance of location in general is further indicated by the fact that the Latin Catholics failed in their attempt to build a church in the city centre. Permission was only granted after the Catholic church changed its location to periphery in New Rustavi. An attempt by Muslims to build a shrine linked to New Rustavi also failed. Interest in New Rustavi is also triggered by the city’s general environmental situation, as most of the factories are concentrated in Old Rustavi. As New Rustavi is more socially active and has had a better infrastructure since the late Soviet period, this part of the city also provides a new opportunity to increase one’s visibility.

To discuss the place and importance of religion in society during the communist era, Dragadze suggested the term ‘domestication’, which refers not to the disappearance of religion but to its shift from public to private, which also involves their simplification. Thus, now, because of this simplicity, they involved more people, especially when faced with illness or life crises. The post-Soviet refashioning of religious life, as Dragadze suggested, can be seen as a way of escaping from communist colonial structures (Dragadze 1993).

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a sharp transformation in religiosity was evident across the country. One of the most noticeable effects of the ending of the communist era was the new religious sites that mushroomed across the country, as well as the old places of worship that were restored and rebuilt. The urban environment of the city became a popular space for demonstrating religiosity. Another reality after the collapse of the Soviet system was the emergence of new, diverse religious groups competing fiercely and beginning to actively seek their place in the new post-atheist and post-secular space. In Rustavi, we find a Muslim community, a group of Latin Catholic believers, the Lutheran Church, a Pentecostal Chapel, a Baptist-Evangelical community and the Kingdom Hall of Jehovah‘s Witnesses, alongside people of other faiths who have not made any claims about their visibility in the city space. In the article, I will only discuss the construction of Orthodox Christian churches in Rustavi, the case of the establishment of Latin Catholics in the city, whose efforts, despite a long resistance, were successful (Loladze 2018), and the Muslim community and its struggles to find a site in the city for their rituals and other religious practices, which has so far proved impossible. It is noteworthy that the last two cases are religious groups that are classified in Georgia as ‘traditional’ (Khutsishvili 2004), despite which it has been difficult for them to establish themselves in Rustavi’s urban environment. The scarcity of, resistance to and search for forms of coexistence are interesting in an urban setting where religious symbols, as well as having sacred significance, possess national and political meanings. It is possible to consider the religious architecture of Rustavi as an example of the embodiment of national and political ideas.

‘Qualities of architecture that do not simply represent something that already exists but that help make and destroy identities, enable and disrupt experience, create, reproduce or break up communities – in short, that makes a change.’ (Verkaaik 2011: 13)

The arrangement of post-socialist spaces in Georgia reflects all the painful processes in Georgian society that are related to the understanding and interpretation of the Soviet heritage. In her article ‘Sharing the not-sacred’, Silvia Serrano discusses the Rabat5 construction project in Akhaltsikhe, the importance of which goes beyond just the restoration of a historical monument. Of particular importance is the fact that the complex includes various cultural and religious buildings. Serrano views the restoration of the complex as an attempt by the Saakashvili government to compete with the attempt of the Georgian Orthodox Church to mark the entire territory of the country and its cultural heritage. According to Serrano, the fact that the construction of Rabat was a political project is also reflected in the circumstance that it was not headed by the Ministry of Culture and Monument Protection of Georgia, but by the then Minister of Internal Affairs, who was originally from the region and had been born into a Catholic family. According to Serrano, the future of Rabat and how it will serve the image of the country‘s multiculturalism is still unclear. To turn Rabat into a shared space, it became necessary to desacralize the public space by transforming the existing religious buildings into museums (Serrano 2018).

Rustavi‘s urban environment and the topography of the religious architecture in the city accurately reflect the contrast between two images of the city, one national, the other international, that deepened after the collapse of the Soviet atheist and secular order and which still continues. The struggle for religious spaces blends with the Soviet genesis of the city, which represents the revival of the historic city with a multicultural, industrial profile. These two contradictory images of the city created by the communists are present in religious forms today and assume the character of a search for new identities. After all, the process of constructing religious buildings and struggling to settle in the urban space may constitute other reflections of the recent past and different interpretations of religious pluralism.

The data for this study were collected during my fieldwork in Rustavi between 2019 and 2020, but they also draw on my earlier research in the city. As my main methods, I have used participant observation and interviewing. I have also used content analysis to analyse various secondary sources. Drawing on my field data, this article addresses the issue of religious plurality as a post-socialist reality in a local context in which the formal and factual understandings of the event are dissimilar.

Construction of the First Church in Rustavi: Instrumentalization of the City’s History

The construction of the first church in post-Soviet Rustavi was a special event, one that went beyond the local context and became significant for post-Soviet Georgia. It is believed the first church to be built in any post-socialist country after the collapse of the Soviet Union was in Rustavi. Currently, there are about 23 active Orthodox churches in Rustavi, and ten more are under construction.6 They occupy a prominent place in the urban space and can be found in a number of advertisements and publications concerning the city. The erection of crosses is also noteworthy, a trend that began when the mayor of the city, Merab Tkeshelashvili, erected an iron cross on Mount Yalghuji, overlooking Rustavi (see Figure 1). This was followed by the erection of iron crosses in yards across the city.7 Rustavi has three distinguished Orthodox churches: Rustavi Sioni, the Church of the Annunciation and the Cathedral. Rustavi Cathedral is distinguished by its magnificence and is named after the Georgian King Vakhtang Gorgasali.8 The name of this warrior king has a special significance for Rustavi, as it provides a wide range of opportunities for national interpretations of the city‘s distant and recent past. The first church in Rustavi, the Church of the Annunciation, is distinguished by its symbolism and is believed to have been built on the ruins of another church. The Church of the Annunciation is also connected to King Vakhtang Gorgasali, as it dates back to the fifth century. Demonstrating the importance of building the first cathedral in Rustavi is a huge responsibility for the city’s community. Its importance is emphasised by both priests in Rustavi and members of the community.

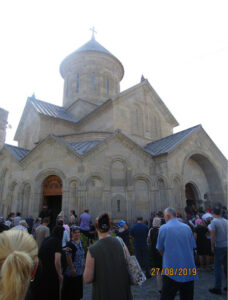

Rustavi Sioni occupies a prominent place in the urban space of the city, both visually and in its content, reflecting the process of its construction. Rustavi Sioni is located in the centre of New Rustavi and is characterized by its many parishioners. On holidays the church cannot accommodate everyone, and most of the congregation joins in the liturgy in the courtyard (see Figure 2).

‘When His Holiness Ilia II visited Rustavi Sioni, he mentioned four times in his sermon:

‘I‘ve seen a miracle’ …

‘rodesats uts’mindesma ilia II-m rustavis sioni moikhila, kadagebashi 4-jer ts’armotkva:

‘me vnakhe saotsreba’’ (Subeliani 2013).

This narrative relates to the technology of Rustavi Sioni’s construction and the symbolism of its historical importance. The church was built utilizing traditional technologies of stone and mortar without cement or other reinforcement. As mentioned by the chief architect, Father Besarion, it was very much a matter of not losing time and of restoring the centuries-old Georgian tradition of temple building.

The construction of Rustavi Sioni took almost ten years, as architects and builders had to study old building materials and their preparation. In addition to the materials and technology, ornamental fragments and reliefs from many famous Georgian architectural monuments were used in the temple’s decoration. Rustavi Sioni shows an eclectic fusion of different forms of Georgian traditional architecture, uniting the style and forms of many famous church monuments. Therefore, Rustavi Sioni, through its combination of all the outstanding forms of traditional church architecture, became an example of history-making in a history-seeking city.9

Karpe Mumladze, the Chairman of the Writers‘ Union of Rustavi in the Soviet period, dedicated the work ‘God is With Us’ (‘chventan ars ghmerti’) to the construction of the first church in Rustavi. The book’s introduction reads:

‘The book tells the story of a pious man and the restoration of a church in Rustavi after a 724-year interval.’

‘ts’igni mogvitkhrobs ghvtismosavi adamianisa da 724-tslovani tsq’vet’ilobis shemdeg rustavshi mghvdelmsakhurebis aghdgenis shesakheb.’

(Mumladze 1991: 7)

The important detail is that generally, somewhat similarly to Hobsbawm’s (1993) ‘invention of tradition’, when a new site of Orthodox worship is built or opened, it is represented as a ‘restoration’ (aghdgena) of something old and historic. This book, published at its author‘s expense, is loaded with emotional elements, starting with its title and ending with the dedication to his late spouse. The unusual text proposed by the author resembles the confession of a communist who has experienced a catharsis. In the introduction, he apologises to the reader for anything he may have said or understood wrongly, hoping that, if he sins when talking about ‘God and the Virgin’, he will be forgiven. The author‘s reflections on the period from 1987 to 1990 are developed interestingly in the text. He speaks of himself as a former communist, who, like other communists, could not dream of a church whose religiosity was hidden from the public space. However, he says that a suitable time has come, that the situation has changed and that something new has begun that has led people to restore the temple of Christ. According to him, everything started with the founding of the Rustaveli Society of Georgia. Of course, his mentioning of the poet Shota Rustaveli in the context of this new era cannot be accidental.

‘A new age, a new situation, an era of transformation again demanded the existence of the Rustaveli Society, but with a new program.’

‘da ai, akhla drom, akhalma vitarebam, gardakmnis epokam isev moitkhova rustavelis sazogadoeba, magram akhali ts’esdeba-programit.’ (Mumladze 1991:6)

The creation of the Rustaveli Society, while the Soviet Union still existed, was supported by the argument that the Communist Party could not respond to the demands of the public because of its narrow-mindedness. The author then speaks of Georgia and the crucifixion of Christ as denoting the same thing: the Cross saved Georgia and will also save it in the future. In his view, although there were no churches in Rustavi in Soviet times, its church ruins always reminded people of their presence, especially during the construction of New Rustavi. What this refers to is the ruins of many churches found by archaeologists during excavations. The communists, according to him, knew about these church ruins, but remained silent about them.

Their silence in this respect was broken by activities initiated by the Rustaveli Society in 1988. The construction of a church in Rustavi was seen as restoring the city’s historical and cultural monuments. In addition to this, the building had been initiated by factory workers. The author of the book, who was actively involved in this process, tells the reader about the steps that were taken to reach the desired conclusion. These processes mainly took place in 1988-1989 and were attended by His Holiness Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia Ilia II. Finally, an archaeological justification was provided for the construction of the first church in Rustavi. This meant that it would be restored and not constructed on the same spot as the original church. It is worth noting that the initiative concerning the construction of a church in the city was connected to the restoration of the temple built by King Vakhtang Gorgasali of Kartli. Thus, the history of the construction of this church in the city of socialist workers is also interestingly related to the communists‘ narrative of rebuilding the historic city, whereas in fact this project was realized through the work of the Rustaveli Society.10

The Church of the Annunciation was built on the ruins of Vakhtang Gorgasali Orthodox church, which symbolized its origins and transformed it into a building with a venerable new age. This transferred religion into the public space. However, the historical existence of Orthodox churches have prompted the appearance of other religious groups. The multicultural atmosphere of the City of Forty Brothers was expected to become the basis for religious pluralism. However, we rarely come across this type of instrumentalization of the city’s narrative, especially with respect to the process of building Orthodox Christian churches, which began before the collapse of the Soviet Union, continues today and occupies a prominent place in the city‘s architecture.

Added to this is the tendency to build massive Christian chapels in the yards of Rustavi apartment buildings, indicating a desire by the Christian population to dominate and occupy a higher place in their public hierarchy. The yard chapels best express the iconography and symbolism of religion. They are organized with contributions from the neighbourhood’s residents through private initiatives, and their construction is often spontaneous. Their size and shape depend on the capabilities and vision of different neighbourhood cooperatives. They conform to no single established style or standard. Some of them resemble a church model, in some places there is an icon with a small shrine and a candlestick, and most often people put up metal crosses and surround them with fences, decorative hedges or other plants. The yard chapel is considered the property of the neighbourhood and serves as its guardian. In addition to protection, yard chapels have acquired prestige (22-year-old woman). From the functional point of view, these churches are merely aesthetic: no specific ritual practices are involved. It is noteworthy that yard chapels with this background have become a phenomenon specific to Rustavi and are practically rarely found in other cities. They can be seen as an instrument in the fight for public space and as a peculiar manifestation of the new order and hierarchy that is dominated by Orthodox Christians.

Construction of the Catholic Church in Rustavi

Georgia has had an active relationship with the Vatican from the early days of Christianity in the country and throughout its history (Ghaghanidze 2008). Most Georgian kings established direct contact with the Pope. Letters depicting this relationship and union date back to the thirteenth century, from which period we can talk about the existence of the Catholic Church in Georgia (Ghaghanidze 2008). Italian and French Catholic missionaries only arrived in Georgia in the seventeenth century. Their influence is indicated by the reference to Georgian Catholics in the Akhaltsikhe district of Georgia as ‘French’. Georgian Catholics have played a special role in the region’s educational and charitable activities. Their aspirations for and contributions to the rapprochement between Georgia and Europe are also noteworthy. This religious community was severely affected during the Soviet era. Out of sixty Catholic churches in Georgia, only one functioned during the Soviet era (in Tbilisi). Today there are approximately 50,000 Catholics in Georgia. Apart from Tbilisi, Catholics are mainly represented in southern Georgia, including those who settled in Rustavi at different stages of the city’s development. The number and importance of Catholic Meskhetians11 in Rustavi may be indicated by the possible existence of a Catholic neighbourhood. As one of my Catholic interlocutors, a 54-year-old man, told me, a small number of devout Catholics travelled to Tbilisi to attend religious services during the Soviet era. At that time the visibility and mobilization of Georgian Catholics was scarcely possible, and given their ethnicity, the claim on religiosity was seldom expressed in the era of Soviet atheism. This indicates that Georgian Catholics had acquired a special position in the multiculturalism of Rustavi.

Rustavi was described in Soviet-era newspapers as a city of brotherhood, friendship, youth and forty brothers (Giorgadze 1978: 3). It is difficult to determine what specific statistics formed the basis for declaring Rustavi a City of Peoples’ Friendship, but Communist Party officials spared no effort to portray Rustavi as a multicultural city. The main avenue in Rustavi was called the Peoples’ Friendship Avenue, and there was also a Peoples‘ Friendship Square, while several other streets were named after Soviet cities famous for metallurgy, like Donetsk, Sumgait or Cherkasy. In the post-Soviet period, this was preceded by the emergence of a strong nationalist movement and the mass emigration from the city of ethnic minorities to other parts of the country and abroad. The city’s multiculturism therefore lost its relevance. In some cases, however, it was instrumentalized by the local government, for example, when a statue of Heydar Aliyev12 was erected in the city. For certain community groups and other civil-society organizations, the topic of multiculturalism has been used as a resource to argue for the need to include minorities. The importance of multiculturalism as a value shared at the state level is indicated by the goals of the Georgian national curriculum, namely to impart knowledge and teach students based on these values (National Curriculum 2018-2024).

Although mentioning Rustavi as a multiethnic and multicultural city is not usual in modern Georgian society, there are some exceptions, for example, a school textbook provided as a supplementary resource for schools: ‘How We Lived Together in Twentieth-Century Georgia’ (‘rogor vtskhovrobdit ertad XX saukuneshi’). The work was written by its authors as part of the project ‘Building Tolerance through History Teaching in Georgia’ and presents Rustavi as an exceptionally positive example of a diverse, multicultural community. The chapter entitled ‘Rustavi: The City of Forty Brothers’ provides specific examples of the peaceful coexistence of different nationalities (Chikviladze 2012). This project was run by a Georgian NGO, the History Teachers‘ Association of Georgia, in cooperation with the Council of Europe. This case is, of course, an illustration of how history may be exploited to select facts from the past when there is a demand for certain values. However, as my ethnographic observations and interviews reveal, this demand comes not from the public, but from the government. It is also noteworthy that the government‘s interest in these topics and their actualization is ‘dictated’ to some extent by international partners such as the EU. Western partners tend to have less knowledge of the local context and urge the country and its authorities to share their ‘contemporary’ views, which implies the sharing and appreciation of diversity, multiculturalism and tolerance as particular values. The fact that diversity is perceived as a threat rather than a value in the context of Rustavi is confirmed by one particular high-profile dispute that later moved from public debate into the courts. This was a lawsuit filed in Rustavi City Court by the Latin Catholic Apostolic Administration against Rustavi Municipality for blocking the construction of a Catholic church in the city (Tabula 2015).

One indicator of the controversy and importance of this issue is the decision of Rustavi Catholics on 7 December 2015, to erect a so-called ‘Door of Mercy’ on the spot they planned to build a church in the central part of New Rustavi (State Agency for Religious Issues 2015). The unusual sight of the Door standing out in the open mirrored the unresolved situation. The Head of the State Agency of Religious Issues of Georgia visited the site and participated in the event to show the state’s neutral position regarding the construction of a Catholic church in Rustavi.

The accounts of Rustavi Catholics that I present below demonstrate the different social, political and cultural dimensions of both the process of the construction of the Catholic church and the general context of the relationship between the local Catholic population and the city’s Orthodox residents.

Leila, 62, a Catholic, came from one of the villages in Adigeni district, southern Georgia, to Rustavi, where she married an Orthodox Christian. She recalled that during the communist era they prayed at home every Friday. Her grandfather had played a particular role in cultivating religiosity in Leila and her siblings. When they grew older and were students, they became parishioners at St. Peter and Paul Church in Tbilisi. In the post-Soviet period, when it came to receiving the sacrament and having a church wedding, they had to make a decision: as she did not want to give up her Catholic religion, the Orthodox Church would not marry them. Here, she noted the generosity of her husband, who agreed to be wed in the Catholic tradition. In this way, her husband did not need to change his religion and remained Orthodox.

Half of Leila‘s family is Orthodox, half is Catholic, her eldest son is a Catholic, and his daughter-in-law is Orthodox. Her religion does not prevent her from lighting a candle in the Orthodox Church. She has a good relationship with an Orthodox priest and her Orthodox neighbours. However, she has received offers to convert to Orthodoxy many times, which seems unacceptable for her. She recalled a period when they were not allowed to build a Catholic church in Rustavi. She discussed this issue from the political angle and recalled the pre-election period in 2012, when one of the parliamentary candidates from the opposition came to her neighbourhood to meet prospective voters. As Leila remembered, the candidate told the population that the government had sold the land to Catholics for the construction of a church, information he represented as a negative act and treason. This made Leila very sad: how come she was ‘different?!’ Weren’t the Catholics also the children of this culture and land?! She also recalled the day the Catholic church was opened in Rustavi, when the mayor repeatedly apologized for opposing its construction. According to Leila, the mayor of the city did not have a proper idea of who the Catholics were.

Father Zurab, the pastor of the Rustavi Catholic Church, whom I have met in Rustavi, talked about the pressure that the Catholic community is experiencing in Georgia. Father Zurab, like Leila, is from southern Georgia and has been serving in Rustavi for less than a year. He was surprised and could not explain the opposition that his community faces in Georgia. He found it difficult to identify where this pressure on the Catholic community comes from, but he singled out two pressing issues that involve the relationship between the two churches. The first was the seizure of the Catholic community‘s cultural heritage by the Orthodox Church, which turned the Catholic churches into Orthodox churches in 1989-91. Since then, the Catholic community has been fighting for their return to their rightful owners. The second issue he identified is the mass conversion of Catholics to Orthodoxy. He mentioned cases in southern Georgia where Catholics were being recruited into service and faced with the choice of either being rechristened and thus keeping their jobs or staying faithful to Catholicism and losing them. Catholics also often had to be rechristened before the marriage ceremony, he said, adding that such pressures are frequent in schools and universities as well.

The important issue is what constitutes a religious group faced with harsh opposition and numerous barriers in the public space. According to unofficial statistics, there are about 150 Catholic families in Rustavi today, the vast majority ethnic Georgians from southern Georgia. They came to Rustavi, like other citizens, in search of fortune and contribute to its diversity. Difference not based on ethnicity was perceived as a threat and turned into a basis for discrimination. As one of the clerics of the Catholic church disclosed to me, many Catholics in Rustavi were baptized as Orthodox because they could not withstand the various forms of oppression they faced (50-year-old man). The argument of the opponents of the Catholic Church was based on a small number of parishioners who prayed on the empty piece of land allocated to the church.

When I tried to talk to the members of a Catholic church in Rustavi, I found that some of them had been rechristened. When I enquired after the reasons for their conversions, they mentioned that they came from mixed families. However, they did not wish to talk about the issue in more detail. The service I attended at Rustavi’s Catholic Church was also attended by only seven believers, four of whom were over sixty. There were no young people at all.

For the Latin Catholics, their church’s construction in Rustavi only became possible in 2018, and then only in a different place. The five-year fight to get permission to build the church was interpreted as a bureaucratic hurdle imposed by the State Agency of Religious Affairs, and the issue was resolved through a change of location. Instead of 500 square metres, 1200 square metres were allocated for the construction of the church, although on the opposite side of the city in a primarily residential area. Thus, the five-year dispute over the establishment of a Catholic parish in Rustavi was amicably resolved, but the Pope‘s intervention and reports in the Italian media concerning the violations of religious rights indicated the seriousness of the problem (Meparishvili 2016).

The Muslim Community in Rustavi

Another major challenge to the multicultural nature of the city and its interpretation as such is the Muslim community’s search for a site for a mosque in the urban area of Rustavi. The largest ethnic and religious minority in Rustavi are ethnic Azeris who are also citizens of Georgia. They make up about 10% of the city‘s population.13 There are currently no mosques in Rustavi. Finding traces of Islam in the city is extremely difficult and can even be considered a taboo. Neither representatives of the Christian majority nor Muslims are willing to talk openly about the issue. There is no publicly stated desire to build a Muslim shrine in Rustavi. When I asked the Head of the State Agency for Religious Affairs whether they had received a request from the representatives of the Muslim community to initiate the building of a shrine, I got the following answer:

‘There has been no request from the Muslim community in Georgia at this stage regarding the construction of a mosque for the Muslim community.’

‘muslimta temis sak’ult’o nagebobis msheneblonastan dak’avshirebit am et’ap’ze sruliad sakaetvelos muslimta sammartvelodan motkhovna ar shemosula’ (Vashakmadze 2019).

It is reported that a Muslim shrine has been opened in a private house in Sanapiro Street, though it is not registered as such, and it is difficult to obtain information about it. Its existence is only talked about, and most of the city‘s population has no information about it. Only a few residents of Rustavi have confirmed that such a shrine existed. An Azeri girl from Rustavi claimed that she had visited the shrine several times during her school years, but does not remember exactly which building it was in. She mentioned that she is not a believer and therefore was not very interested in such matters. Her parents are not active believers either; they prefer to celebrate religious holidays within the family’ (23-year-old woman 2019).

Information concerning Muslim prayer houses is not available online.14 A young Azeri, a citizen of Georgia who considers himself a devout Muslim, maintained that in the early 2000s there was indeed a gathering of Muslims in a rented house in Rustavi near Sanapiro Street. However, he has not heard anything about the shrine since then. He says believers gather in different places to pray.

‘Now, a few days ago we had important days for Shia Muslims. We remembered Mohammed‘s grandson for ten days. Since we don‘t have a meeting place, we rented a restaurant and paid 100 GEL a day. What else could we do?’

‘akhla ramdenime dghis ts’in, chventvis, shia musulmanebisatvis mnishvnelovani dgheebi iq’o. vikhsenebdit muhamedis shvilishvils, 10 dghis mandzilze. radgan shek’rebis adgili ar gvakvs, vkiraobdit rest’orans, ert dgheshi 100 lars vikhdidit, aba ra gvekna? (29-year-old man 2019).

The man listed three problems that he believes Azeris living in Rustavi have long been concerned about: the absence of a cemetery, a mosque and a school building. The problem concerning the cemetery has recently been resolved, as the city hall allocated a plot to Muslims a few months ago. As for the mosque, he remembers that its construction was prevented by the Orthodox Christians. This fact cannot be confirmed because it has not been disclosed. Only a small part of the Rustavi population remembers these developments through having witnessed them. An Orthodox girl from Rustavi who commuted on a daily basis to Tbilisi, where she was a university student, considers her native city to be ethnically and religiously diverse. For her, there are no problems apart from that regarding the mosque. According to her, there is an uninhabited area near her apartment. The Azeri population applied to the Mayor’s office for access to that area, but the Christian population protested at the construction of the mosque. Residents collected signatures from apartment owners, based on which the municipality decided not to permit the building of a mosque, thus ending the matter. The woman recalls that she was in school at that time, meaning that it must have happened in 2009 or 2010 (24-year-old woman 2019).

Thus, for Muslims, there are many obstacles to their entering the public space in Rustavi. Despite their significant numbers, their position is not or cannot be expressed publicly. The absence of a Muslim shrine in Rustavi can be explained by several factors, one being the higher rates of integration of Azeris into mainstream Georgian society, who do not want to risk their good relationship with their Georgian neighbours. Unlike many of their co-ethnics living in other parts of Georgia, Azeris living in Rustavi have a perfect command of the Georgian language, indicating their close connection with the Georgian population of their city. Another important reason for the absence of any mosque in Rustavi may be connected with the fact that there are many predominantly Azeri villages near the city and that Rustavi Azeri Muslims go there for religious services. They also have in mind the negative environment created by the erection of a monument to Heydar Aliyev15 in Rustavi in 2013. All in all, the absence of any Muslim shrine in Rustavi does not cause much anxiety or a desire for open resistance on the part of the local Azeris and their relations with the Georgian population at large. The community of Azerbaijani speakers does not want to hinder the process of their integration with ethnic Georgians by demanding the right to public religiosity (29-year-old man).

Conclusion

In conclusion, Rustavi is an interesting place for analysing the place of religion in the post-socialist, post-secular or post-atheist reality. The demand for religious expression in the city, which previously had no sacred sites, increased after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Church construction started not only with the building of new shrines, but also with the revival of existing ones by uncovering the city’s different archaeological layers. According to the Soviet national narrative, the communists rebuilt the historic city. The industrial part of Rustavi was built on the foundations of a medieval town through the support of the Soviet Union’s fraternal union. The revival of the city’s national narrative proposed by the communists includes the massive construction of the city‘s Orthodox churches. The symbolic significance of these churches goes beyond religious activities and reveals a discourse within the fight for power and power relations. If the construction of the Orthodox churches echoes the city‘s national narrative, the ways in which religious plurality is handled in Rustavi goes against its international, multiculturalist narrative as the City of Forty Brothers. This may be related to the decline of industry and the outflow of population from the city. If the issue of religious pluralism in European cities is related to migrants and the migration process, as Giordan noted (2014), in this case, the representatives of different ethnic groups migrated from Rustavi to other parts of Georgia and abroad. The changed ethnic composition that resulted has had a negative impact on Georgians‘ acceptance of pluralism as a value. An example of this is the legal dispute over the right of Latin Catholics to build a church in Rustavi in which even the Pope interfered. Despite the existence of an Evangelical-Protestant church, now Catholic, and the religious buildings of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Rustavi, there is no mosque or Muslim shrine, even though Muslim Azeris are the second-largest ethnic and religious group in the city. This fact may also be related to the peculiarity of perceptions of Georgian history, in particular the image of Rustavi as a ‘medieval’ Georgian city. Altogether, the urban space of Rustavi, seen through its religious buildings and related narratives, reflects a fight for power and for the creation of a new order in a city that is otherwise devoid of significance. The iconic representation of religion in Rustavi’s space reflects the post-atheist revival of different religious groups and the power relations between them.

Note on the Author

Tea Kamushadze holds PhD in anthropology. She is assistant professor in cultural anthropology at Georgian Institute of Public Affairs (Gipa) and she is a researcher at Ivane Javakhishvili Institute of History and Ethnology (TSU). Her research interests include post-socialist transformations, anthropology of religion, representation of history and memory in post-Soviet urban space and traditional forms of socialization. Currently she is working on her post-doctoral project: “Representation of Religious Pluralism and Secularism in Urban Space: Post-Socialist Rustavi” (2019-2021).

Email: tea.kamushadze@tsu.ge

References

ARALI. 2018, Octomber 6 rustavshi k’atolik’uri t’adzari ik’urtkha. (Catholic church was consecrated in Rustavi): https://katolicblog.wordpress.com/2018/10/06/

BERGER, L, P., 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Boston and Berlin: Walter De Gruyter.

BERKING, H. SCHWENK, J. STEETS, S. 2018, ‘Introduction: Filling the Void? – Religious Pluralism and the City. In: Helmuth B., Schwenk J., Steets S. (eds). Religious Pluralism and the City: Inquiries into Postsecular Urbanism. London, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic, 1-24.

CASANOVA, J., 2013, Religious Associations, Religious Innovations and Denominational Identities in Contemporary Global Cities. In: I. Becci, M. Burchardt & J. Casanova, eds. Topographies of Faith: Religion in Urban Space. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 113-127.

CHIKVILADZE, T., (ed) 2012. Rustavi – ormotsi dzmis kalak (Rustavi – city of forty brothers). Tbilisi: Georgian Association of History Teachers.

CURRICULUM, P., O. 2018-2024, June 29. http://ncp.ge/en/home. Retrieved from http://ncp.ge/en/curriculum/general-part/introduction: cp.ge/curriculum/satesto-seqtsia/akhali-sastsavlo-gegmebi-2018-2024/sabazo-safekhuri-vi-ix-klasebi-proeqti-sadjaro-gankhilvistvisfile:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/%E1%83%

DRAGADZE, T., 1993. ‘Domestication of Religion under Soviet Communism’ in Hann, C.M. (ed) Socialism: Ideals, Ideologies, and Local Practice (London, Routledge).

GHAGHANIDZE, M., 2008. k’atolik’uri ek’lesia (Catholic Church) N. Papuashvili eds. In religiebi sakartveloshi (Religions in Georgia) Tbilisi: sakartvelos sakhalkho damtsvelis bibliotek’a (Georgian Ombucman Library).

GEOSTAT 2014, Census of all Georgia (Rustavi ethnic belonging).

GIORDAN, G., 2014. Introduction: Legitimization of Diversity. In: G. Giordan and E. Pace, eds. Religious Pluralism. Framing Religious Diversity in the Contemporary World. New York: Springer, 1-15.

GIORGADZE, R., 1978, February 4. ormotsi dzmis kalaki (City of Forty Brothers). samshoblo, 3.

HOBSBAWM, E., 1993. Introduction: Inventing Traditions. In Hobsbawm, E & R. Ranger (eds) The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1-14.

IMEDI NEWS, 2018, Octomber 4. rustavshi k’atolik’uri ek’lesia ikhsneba (Catholic church opening in Rustavi). Retrieved from Imedi News: https://imedinews.ge/ge/saqartvelo/79960/rustavshi-katolikuri-eklesia-ikhsneba

KAMUSHADZE, T. 2017, ორმოცი ძმის ქალაქი იდენტობის ძიებაში (The City of Forty brothers in search of identity) in Anthropological Researches, p 171-194, Tbilisi.

KHUTSISHVILI, K., 2004, religiuri sit’uatsiis tsvlileba da usafrtkhoebis problema sakaqrtveloshi (Changes in the Religious Situation and the Problem of Security in Modern Georgia). Tbilisi: memat’iane.

KNOTT, K. V. & MEYER, B., 2016. Iconic Religion in Urban Space, Material Religion, 12(2): 123-136, DOI: 10.1080/17432200.2016.1172759

LOLADZE, R., 2018, The Catholic Church was inaugurated in Rustavi. Tbilisi: Public Broadcaster.

LOMTATIDZE, L.,1975, shavi orshabati (Black Monday). mnatobi, 152-156.

MAGHLAKELIDZE, N., (2017, 12 25), The Tbilisi Times. Retrieved 02 12, 2020, from Rustavis Sioni – ‘bienales’ saertashoriso konkursis gamarjvebuli: http://www.ttimes.ge/archives/87268

MEPARISHVILI, M., 2016, rustavis sasamartlom k’atolike ek’lesiis sarcheli daak’maq’opila (Rustavi court upheld Catholic church lawsuit) [on-line edition] (Netgazeta, published from 8 June, 2016). add.: http://netgazeti.ge/news/121968/

MUMLADZE, K., 1991, chventan ars ghmerti (God is with us), Tbilisi: Merani.

PELKMANS, P., 2003 Uncertain Divides: Religion, Ethnicity, and Politics in the Georgian Borderlands, Universitet van Amsterdam.

SERRANO, S., 2018 Sharing the Not-SacredRabati and Displays of Multiculturalism. In: T. Darieva, F. Mühlfried & K. Tuite, eds. Sacred Places, Emerging Spaces Religious Pluralism in the Post-Soviet Caucasus. New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 203-225.

SERRANO, S., 2010 De-secularizing national space in Georgia. Identity Studies in the Caucasus and the Black Sea Region, 2, 5-20. (hal-01533778)

State Agency for Religions Issues. 2015. ‘https://religion.gov.ge/en/publikaciebi/saqartvelos-saxelmwifos-religiuri-politikis-ganvitarebis-strategia-proeqti.’ https://religion.gov.ge/en. June 29.

TABULA, 2015, November 19. k’atolik’e ek’lesia sakartveloshi rustavis merias disk’riminatsiis gamo uchivis (Catholic Church in Georgia sues against Rustavi City Hall for Discrimination). [electronic magazine]

VASHAKMADZE, Z., 2019, Respond to your requests. Tbilisi: LEPL State Agancy for Religious Issues.

VERKAAIK, O., ed. 2013, Religious Architecture: Anthropological Perspectives. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

New Diversities • Volume 23, No. 2, 2021

Special issue: Urban Religious Pluralization: Challenges and Opportunities in the post-Soviet South Caucasus

Guest Editors: Tsypylma Darieva (Centre for East European and international Studies) and Julie McBrien (University of Amsterdam)

- ISSN-Print 2199-8108

- ISSN-Internet 2199-8116

- Founder of the Rustavi Drama Theatre, together with a group of young artists, Lortkipanidze moved to Rustavi from the Kote Marjanishvili Theatre in Tbilisi. Because of a conflict with the older generation of artists, this event was considered a kind of revolutionary step in Georgian cultural life.

- It has been argued that in the Soviet Union communism and ‘‘Scientific Marxism’’ assumed the form of a sort of religion (see Dragadze 1993). However, my engagement with the term ‘‘religion’’ is more conventional and does not aim to analyse the religious-like nature of the Soviet Union’s communist ideology.

- The City of Forty Brothers became one of Rustavi’s brand names, which the communist regime was actively trying to replicate and popularize. It is difficult and even impossible to talk about how Rustavi came to be known as the City of Forty Brothers, but the goal is easy to grasp: to create an image for the city as multiethnic and multicultural. The names of the city’s streets and squares can also be used as an example to express the friendship between nations and peoples. The mass migration of non-Georgians from Rustavi took place in the 1990s, dramatically changing its ethnic composition.

- All interviewers and interlocutors are representatives of different religious groups living in Rustavi or were involved in the construction of religious buildings in the city.

- Rabat is a medieval fortress that was built in the ninth century and became a main residence in the region in the twelfth century. It is located in the southern part of Georgia in Akhaltsikhe, where we can observe layers of different cultural heritage down the centuries: an Orthodox Christian church, traces of Latin Catholics, a mosque, a Jewish neighbourhood etc. In 2011-2012 Rabat was restored by Saakashvilis’s government and was presented as evidence of a tradition of tolerance and of the peaceful coexistence of different cultures.

- Official website of the Patriakhat of Georgia: https://patriarchate.ge/news/1608

- Merab Tkeshelashvili, Mayor of Rustavi between 1996-2005.

- Vakhtang Gorgasali, a great warrior Georgian King of Kartli from the fifth century, and known as one of the founders of Tbilisi.

- Sioni Cathedral won a Grand Prix and Gold Medal at the World Architecture Exhibition in Sofia 2012 as the best example of ‘‘tradition and innovation’’ (Maghlakelidze 2017).

- In an interview with me, Lasha Khetsuria, Rustavi resident, claimed that in 1988 he and his friends initiated the building the first Christian church in Rustavi, but it appears that their petition and signatures have been ignored more recently (2021).

- Georgian ethnographic groups living in southern Georgia are called Meskhetians, Meskheti being one of Georgia’s historical provinces.

- President of Azerbaijan from October 1993 to October 2003.

- These data do not correspond to Geostat’s statistics, but speaking unofficially with community members, they indicate this figure for the Azeri population in Rustavi.

- Website of Administration of Muslims of all Georgia: http://www.amag.ge/

- A monument to Heydar Aliyev, the second president of Azerbaijan, is located in ‘‘Old Rustavi’’, in the Alley of People’s Friendship. The opening ceremony was organized by the Ivanishvilis government in 2013. Unlike the official television, social media drew much attention to the fact and actively discussed related issues Most of the comments were negative, asking why Heydar Aliyev deserves such an honour. As my interlocutors told me, because of the monument some of them refused to walk in a park for some time.