New Diversities • Volume 25, No. 1, 2024

Wuppertal: Becoming a Haut Lieu and Symbolic Space of Dance through Diversity

by Marion Fournier (University of Lorraine)

To cite this article: Fournier, M. (2024). Wuppertal: Becoming a Haut Lieu and Symbolic Space of Dance through Diversity. New Diversities, 25(1), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.58002/k6gt-nw88

Abstract:

The works of the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch constitute an œuvre that has won widespread global renown since the 1970s. After joint productions and tours in cultural capitals, the company has become more and more cosmopolitan and has attracted international audiences. Consequently, the city of Wuppertal has come to occupy a position of centrality in the dance world. The concept of an haut lieu in French—translated into English by “symbolic space” and originating in geography (Debarbieux 1993)—allows us to grasp such a phenomenon. In this article, Wuppertal is considered to be an haut lieu for four reasons: it is a real and located space; it has a strong symbolic dimension and is highly valued by dancers and audiences; it generates a flow of people; and it is experienced collectively. How do these aspects intersect with diversity? The analysis discusses this nexus by focusing on the city of Wuppertal, the Lichtburg dance studio, the Pina Bausch Foundation and Tanztheater Wuppertal, as well as the theaters where the company performs.

Keywords: haut lieu, geoaesthetics, mobility, diversity, dance

Introduction

The German choreographer Pina Bausch was born in 1940 in Solingen, in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW). She was largely responsible for developing Tanztheater, a particular dance style stemming from Expressionist dance, in Germany as well as abroad. After her dance education and her first works, she became the director of Wuppertal Ballet in 1973. Up until 2009, when she passed away, Pina Bausch created more than forty works with the Tanztheater Wuppertal, her dance company. The rise of the Tanztheater phenomenon within the confines of Wuppertal, both as an artistic genre and as an institution deeply rooted in a specific cultural heritage encompassing norms, practices and narratives, can be analyzed comprehensively because it includes different disciplines, such as aesthetics, geography and history. This analysis can also be viewed as an addition to the field of innovative geography. Despite the fact that the Tanztheater company has met with very great success worldwide and has traveled a lot, its choreographer and dancers have always been based in Wuppertal, a city of 350,000 people, which explains why the choreographer’s name is very often linked with that of Wuppertal.

This paper aims to elucidate the process whereby Wuppertal has established itself as a prominent cultural hub for dance. While this case study represents just one example among many in the art world, it offers a compelling opportunity to delve into the intricate mechanisms underlying the emergence of an artistic center and its consequential renown. Specifically, it allows us to examine the pathways through which a work diffuses across space, as well as a dance company’s inclination to both root and uproot itself, thereby facilitating an exploration of the dialectic between artistic mobility and immobility. These two aspects, despite appearing as seemingly contrasting facets, are mutually supporting, like two sides of the same coin.

Wuppertal has consequently experienced a growing influence way beyond its boundaries. From the mid-1970s, the city has attracted dancers and spectators of many nationalities. This centrality incorporates suburban zones not only around the city but also around the world. Wuppertal occupies a particular position in the dance world, given the fact that Tanztheater refers to a German territory and that it has become this genre’s emblematic city. From a specific local dimension, globally Wuppertal has come to be seen as an inescapable place that embodies the artistic genre called “dance-theater.” The company’s functioning and critical reception intersect very closely with the notion of an haut lieu, which appears to be the most relevant in explaining how this local space has become a symbolic space beyond its borders. If Wuppertal is a dance haut lieu and a central and symbolic place for the Tanztheater company, Pina Bausch in fact took artistic mobilities from the north (Germany) to the south, with a pronounced attraction for southern countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Chile), at the center of her creation through travels and joint productions abroad. From 1986 to 2009 we can observe this process as an “idealized artistic decentralization” (Barriendos 2014: 157; transl. Fournier) and a centrifugal flow from Wuppertal to other, mostly southern countries. The example of Wuppertal refers constantly to the idea of mobility but emphasizes immobility as well. This mechanism also highlights an interesting link between the French word dépaysement (escape or disorientation) and the notion of rooting, a link that is placed at the heart of the aesthetics that Pina Bausch proposed through her works. The notion of an haut lieu can help us grasp this paradox.

The mechanisms of the haut lieu have been theorized by Bernard Debarbieux. In geography, this concept refers to a place that has a high position on a scale of values. According to Debarbieux’s minimalist definition, an haut lieu is a “place deliberately and collectively erected as the symbol of a system of social values” (Debarbieux 1993: 5-6; transl. Fournier). The symbolic dimension comes with other aspects: it is a located space, it generates human flows, it is identified by a social marker, and last but not least it is identified collectively (Clerc 2004). This last point already makes it evident that an haut lieu interacts closely with mobility and diversity. The combination of all these criteria can make a place an haut lieu. Therefore, in those terms, Wuppertal can be considered as such. This article shows how Pina Bausch’s works have contributed to making Wuppertal an important place for the dance world. We start by presenting Wuppertal as a local and symbolic spot for a global travelling company. Next, we describe the dance company’s studio and explain its particular dimensions, which emerge from its status as a shelter. We then discuss the power of translocal and transnational influences, acquired through two organizations that have collected and conserved the company’s archives. Finally, theaters in which the plays in Pina Bausch’s repertoire are performed illustrate a collective investment represented by dancers who are no longer seen as cosmopolitan but also as “cousins from Wuppertal” (Sirvin 2001; transl. Fournier). This sheds light on the complex interplay of emotions between the audience, the dancers, and the urban environment, thereby forging a unique emotional dimension.

The corpus analyzed in this paper comprises works from Tanztheater’s repertoire. It is based on press archives, video archives of public representations (from the 1970s to the 2000s), semi-structured interviews1 with dancers and spectators in France and Germany, and a databased created with the cartographical tool/software showing circulation of the works from the 1970s until today. It exhaustively covers France and Germany, which are our study’s precise fields, as well as, more partially, the works’ worldwide circulation. Press articles serve as primary sources of reception, offering valuable insights into the expectations and aesthetic experiences that are situated within a specific time and place. These articles provide important interpretive frameworks that must be considered in order to grasp the nuances of audience reception and the broader cultural context surrounding the artistic works. In a cultural approach, working on the works’ reception is relevant because cultural and social representations of space are very often mentioned in newspapers. Combined with aesthetics, this approach builds on cultural history and cultural geography in order to create an enlightening analytical device.

Methodological Approach: A Contribution to a Geoaesthetics of Reception

This article is part of a larger study in the arts and defines its method by crossing an aesthetics of reception, as formulated by Hans Robert Jauss (1978) in reception theory, with the geoaesthetics of Joaquín Barriendos (2009). The notion of a geoaesthetics has several aspects. First of all, it studies the influence of every geographical factor—the ensemble of spatial conditions such as territory, country or place—on the reception of an artistic work. The term then refers to the study of the effects of cultural geography—nationality or language, for instance—on theatre plays (here called works) and their reception, as well as on the artistic and international relations that are central to the circulation of an artistic work (Quirós and Imhoff 2014).

A few words should be mentioned here about the theoretical background to this study. In the columns of the scientific journal L’Espace géographique, Jean-Marc Besse highlights one of the presuppositions that leads the cultural disciplines to deploy spatial approaches, a reference to the work of Dario Gamboni and Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann. “Artistic creation,” writes Besse, “isn’t realized apart from the conditions of space and place” (Besse 2010:212-13; transl. Fournier). An analytical grid is here excerpted from a cross-disciplinary literature review in cultural history, cultural geography, and aesthetics. An exploration of common objects of research is needed to maintain a theoretical balance between these three fields. This interdisciplinary approach certifies the specificity of the thesis, which aims to describe the cosmopolitan spatial contexts of Bausch’s works in order to enlighten the terms of the conditions of their emergence. Artistic recognition and notoriety are components of a geoaesthetics. The work’s diffusion, intrinsically linked to expressions of notoriety, is to be considered by tracking its circulation. This approach reflects the increasing presence of spatiality in the history field. In his historical and aesthetic approach to performance, Roland Huesca mentions that the inclination toward space comes from the geohistory of Marc Bloch, Lucien Febvre and Fernand Braudel. He uses the term “geo-esthétique” (Huesca 2010: 46) to remind us that history is about circulation, the circulation of people, knowledge and expertise, as well as intercultural situations. Huesca states that geography is the “guiding principle for economics and politics” (2010: 46; transl. Fournier). Can the same apply to the arts as a way of catching the evolution of artistic works? The present article follows this direction by choosing to present the impact of a specific place on a larger and a global dance scene. It also takes Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch out of dance studies. The existing specific scholarly literature often focuses on the creative process of the works and provides a brief analysis of their reception, while giving relatively less attention to the intricate mechanisms associated with their journeys, trajectories, and mobilities. However, Tanztheater Wuppertal deserves to be regarded as an object of comprehensive study, employing conceptual tools from diverse disciplines. Such an approach allows us to demonstrate its status as an example that explores migration processes within the arts, highlighting the interplay between global trajectories and local re-anchoring. Additionally, it contributes to the discourse on the ascent of notoriety through global itineraries, shedding light on the complex dynamics at play in the field of cultural recognition.

What is exactly a special place in our research fields? In the collective publication Géoesthétique, the historian Piotr Piotrowski (2014: 123) shared his ambition to do a “horizontal” history of art and proposed to focus more on cities that might be seen as marginal. From this innovative point of view, we could highlight new aspects of what is a research object. At first sight, Wuppertal doesn’t appear to be an artistic capital, more often than not being relegated to a peripheral rank, mainly by French audiences and their critical reception. Nevertheless, Wuppertal has progressively built up a form of cultural centrality. It is worth noting that Germany’s cultural policies are organized at the federal level, allowing medium-sized cities to achieve significant symbolic value and centrality within the art scene. Such cities, such as Wuppertal and Essen, both former industrial areas, have established themselves as cultural hubs with renowned schools, museums (in Essen), and strong support networks locally, regionally and nationally (the Stadt, Land, and Bund). Examining the development of this phenomenon in a medium-sized town is crucial for documenting such occurrences in federal countries and dispelling the notion that innovation is solely confined to large metropolises. Furthermore, it provides insights into the distinctiveness and strategic reflexes that are inherent in iconic projects. While the notion of an ecosystem could also have been employed to comprehend the innovative nature of Tanztheater from a socio-economic perspective, our focus lies on the concept of the haut lieu. This concept not only elucidates centrality in terms of its symbolic nature, it also allows us to delve into the realm of the imaginary and to see how it influences the perceptions and representations of a place. The aim here is to specify the driving forces and benefits of Wuppertal’s constructed position in the dance world. Moreover, it is also about providing the tools of a specific study of dance that is largely influenced by geography.

Constructing this geoaesthetics of reception questions the emergence of an haut lieu through the link between artistic circulation and artistic recognition. Our hypothesis follows three steps: first, foreign cities give artistic recognition to works; second, recognition conferred on an œuvre eases and expands its circulation; finally, once acquired, this recognition can reach a global scale, and a process of reterritorialization can start by keeping the œuvre in a very symbolic place that we propose to call an haut lieu of dance.

Wuppertal: A Local and Symbolic Spot for a Worldwide Travelling Dance Company

Within this framework, the word “circulation” will be understood by considering the incessant back and forth between Wuppertal and other places of the production and diffusion of Pina Bausch’s works. From city to city, the company’s circulation created a strong sense of notoriety. Hence a first stay of the company in France, in Nancy in 1977, gave the work significant artistic recognition. The initial visit to Nancy demonstrated the Tanztheater Wuppertal’s ability to identify Nancy as a vector for cultural exchanges and transfers, thereby establishing a spatial strategy in which Nancy assumes a crucial role in its international success. During the following years, various joint productions abroad confirmed the company’s reputation beyond Germany. By the end of the 1970s, critics from metropolitan and other renowned places were starting to praise the choreographer, and the company was welcomed in a city that multiplies artistic centralities, namely Paris, and more precisely the Théâtre de la Ville. In the early 1980s, Paris became the first place to see a work by Tanztheater. In fact, since the World Premiere in Wuppertal, Paris has usually been the second venue for the company’s creations. In 1986, the ensemble initiated works in joint productions with theatres abroad: Rome in 1986 with the play Viktor; Sicily in 1989 with Palermo Palermo; Madrid in 1991 with Tanzabend II; and Masurca Fogo in Lisbon in 1998. Tanztheater’s notoriety allowed its circulation by increasing the number of its international tours, privileging cooperation with other countries, and diffusing filmed images of the works all over the world. The easy and stable relationship with other theatres in the world offered Bausch the opportunity to relocate her company to a city with more artistic influence several times during her career, but she always declined it (Meyer 2016: 88). Nevertheless, this situation presents an enticing opportunity for a dance company to capitalize on. The decline signifies a yearning for local grounding, driven by the potential for local inspiration and the ongoing pursuit of a harmonious balance between a change of environment and a return to familiar routines. This oscillation is widely regarded as fertile ground for artistic creation and finds spatial embodiment through the symbolic positioning of the Lichtburg studio. Thus, the œuvre experienced a reterritorialization back to its birthplace. Dancers’ and works’ starting and arrival points have always been Wuppertal.

In fact, the company’s mobility has to be understood in relation to a constant local rooting. These two dimensions might appear paradoxical, but they depend on each other. The more the company travels outside Germany, the more Wuppertal expands its symbolic dimension and its centrality. First of all, the fact that dancers keep returning to this location in order to create, rehearse, and perform gives Wuppertal a privileged status regarding works’ creation and diffusion. Second, the connections abroad in European as well as North American, South American and Asian cities have given Bausch’s works worldwide artistic recognition over decades. In fact, the reverse is also true: the more the company considers Wuppertal a rooting space, the more networks abroad and travelling devices are strengthened. There are a number of reasons for this. Wuppertal’s prominent position as a venue for the creation and premieres of dance performances can be attributed to its unique approach. While the company had the opportunity to produce its works jointly abroad during its inspirational journeys, the choreographer and dancers consciously chose to prioritize Wuppertal as the primary site for their productions. This deliberate decision aims to enhance the city’s symbolic and emotional significance for both the creators and the audience. By fine-tuning their creations on site, they strengthen the bonds between the city and the artistic works it stages, despite their extensive artistic mobility. This choice highlights the company’s commitment to Wuppertal and reinforces the city’s role in the creative process.

Let us now illustrate this artistic mobility. Works have been performed in about 130 cities in 46 countries in the past forty years. Most of these travels throughout the world were supported by cultural institutes in Germany and/or abroad. Except for Wuppertal, the Tanztheater’s tours have mainly involved megacities, focusing on global art stages such as Paris, London, New York and Tokyo. Two different types of circulation can be seen: tours and joint productions. In the first case the ensemble performs works on stage for an audience, while in the second case dancers visit a city during a specific period, which might be a source of inspiration for a new work, and spend some time there finding choreographic materials and ideas, as well as rehearsing.

Wuppertal as a Local, Fixed and Physical Place

Before focusing on the symbolic value conferred on Wuppertal, let us underline the fixed and physical dimensions of such a place. How and why does Wuppertal remain a stable point of return for both dancers and audiences? And what is its appearance regarding the notion of centrality? How is it organized topologically? A first fact is important to mention because it gives Wuppertal a front-row seat: all the World Premieres take place in Wuppertal. Even the premieres of works produced jointly with much more influential cities take place in Wuppertal. If it is not comparable to cultural capitals such as Paris, London or New York, it endorses a special and diversified centrality. Contrary to its perception as a periphery, which is often emphasized in its reception in France due to the highly centralized vision of cultural policies that prevails in the French press, Wuppertal embraces its distinctiveness. Wuppertal enjoys territorial dynamics provided by the network of cities and an easy circulation thanks to the geographical proximity of these cities to the Land of NRW, a region marked by its high population density. Wuppertal is bordered by cities of different sizes: the metropoles of Cologne and Düsseldorf, the cities of Dortmund or Essen, and other medium-size cities such as Solingen, Remscheid, Hagen, Leverkusen or Bochum. This observation on a regional scale is just meant to recontextualize Wuppertal’s geographical position. Here is the occasion to recall the framework of this research, which is less a comparison between countries than between cultures. Therefore, center and periphery do not refer to the exact same phenomena in France as in Germany, and if Wuppertal is not a center like Paris is in France, it shows a different conception of centrality. It thus comes as no surprise that Wuppertal has an important flow of spectators. Many of Tanztheater’s works are sold out within a few days of the tickets being put on sale. This expresses a large and certain radiance of the position of Wuppertal that goes beyond the local and national scales. Through representations of works and festivals initiated by Bausch, Wuppertal has maintained a link with an emergent creation outside Germany. In this way, Tanztheater Wuppertal’s stage has built itself up through this permanent back and forth between other stages. Moreover, and with the vision of a network in mind, it is 25 km away from Essen-Werden, location of the Folkwang Universität der Künste, an art school that is considered one of the best in Europe. Indeed, this is the school where Bausch received her own education, as was also the case for a lot of the dancers who joined the company. The academic and teaching institution in Essen-Werden represents a potential source for the succession and ensures the transmission of an artistic legacy. Dance is usually transmitted on the basis of an “empiric process” (Apprill 2015). The geographical proximity linking the students in Essen-Werden with the dancers in Wuppertal allows a “corporal transmission” (“corps-à-corps” in Apprill 2015). We note the example of Sacre (1975), which is danced regularly by students from the Folkwang Universität der Künste. It is less about the migration of human beings than about mobility and movements of knowledge and know-how through a geoaesthetics. The migration, in those terms, can no longer be considered a migration of human beings but rather a migration of tastes, styles, shapes, movements, arts, and aesthetics. The issue is to understand how works circulate and to specify the conditions of their circulation. Here the work’s authenticity and its updating process is perpetually renewed through this close learning link between Wuppertal and Essen.

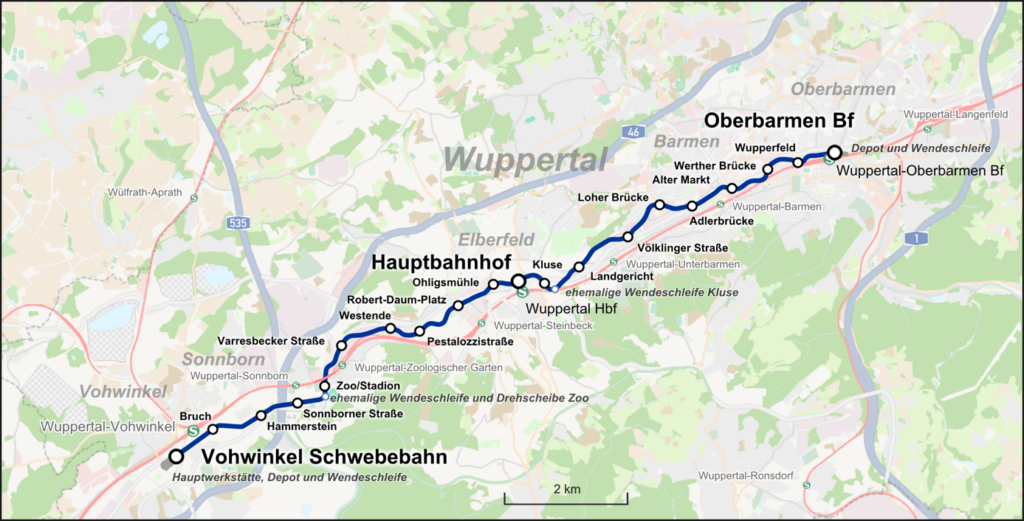

In addition to a fixed location, and in accordance with Debardieux’s definition, an haut lieu has to be visually recognizable in the landscape. The singular morphology of Wuppertal relates to this point. Indeed, it is built along the Wupper river, and it is enclaved between two valleys (Figure 1). It has an element of distinction that makes it quickly identifiable, notably thanks to its height: the sky train, the Schwebebahn. Often represented in the imagery (created by the critical reception of Bausch’s œuvre: we can recall here Wim Wenders’ movie Pina, 2009), the Wuppertaler Schwebebahn is often associated with the Tanztheater Pina Bausch. Even decontextualized from its real space, this particular element evokes a whole part of dance history within an imaginary of dance that is known across the world and is relevant to the notion of the haut lieu.

A Space with a Symbolic Dimension

Beyond being a local and physical space, Wuppertal embraces a symbolic dimension, this being one of the conditions for a space to be considered an haut lieu. In this way, the critical reception of Pina Bausch’s work in the French press between the 1970s and 2000s offers an interesting point of view on narratives of Wuppertal made by projected representations of the city. In the French media, Wuppertal is regularly associated with the Ruhr, despite the fact that the city is actually located in the Bergisches Land, slightly south of the Ruhr. As Debarbieux writes in his paper: “The symbolic nature of the haut lieu allows it to be dissociated from its spatial context. Very few people know where Woodstock is; no one really knows where Alesia is. But it does not matter. Two events took place there; so those places exist (unlike imaginary places), and it is an essential condition of their symbolic functioning; regardless of their location” (Debarbieux 1993: 6; transl. Fournier). Wuppertal’s location does not matter as long as Bausch’s creations and their premieres take place there. Critics’ articles spotlight Wuppertal when they cover a company’s event, even when they are not able to locate it on a map. The social interest of this geographical space is no longer about its location, but about what it represents. Bausch is often called “Lady of Wuppertal” in the press, for instance. This very tight link between a place and a personality in dance is not an isolated case: take, for instance, the case of the Béjart Ballet Lausanne (Gonçalves 2019). And such an appellation is not anecdotal: it links the figure of the choreographer directly to the name of the city as if the two were completely commutable. This commutable aspect shows how a city can endorse a symbolic value. Through this kind of designation, Wuppertal is no longer just a fixed location, it also symbolizes a whole dance oeuvre, being mentioned before the name of the choreographer herself.

In the shadow of “global cities” (Sassen 2002, Paquot 2011: 19), Wuppertal is a historic place for Tanztheater, as it was “popularized by Pina Bausch” (Georget and Robin 2017: 70), and it appears as the privileged city for the diffusion of her work. However, the haut lieu does not exactly refer to the entire city, and our analysis can be specified by focusing the discussion on some other places, leading us to explore and to question our mental map of the city. Key places within the city can be mentioned: the Lichtburg studio, the Pina Bausch Foundation and Tanztheater Wuppertal, and the theaters where these works are performed. This corresponds respectively to one place of creation and two institutional sites and spaces of diffusion.

The Lichtburg Dance Studio: One Particular Place and a Shelter for Cosmopolitan Dancers

Since 1979, the dancers have been creating in a studio set up in a former cinema called the Lichtburg (Meyer 2016: 88). Its walls inspire some of Bausch’s work, for example, the wall of Palermo Palermo in 1989 (Wenders 2010:16). The dance studio is located in a building which is not particularly remarkable at first sight. It is located in the middle of Barmen, a neighborhood in the east of Wuppertal, on the main street called Höhne and on top of a McDonald’s fast-food restaurant (Figure 2). But this place is also far from ordinary according to the dancers themselves, and it even has a front-row seat in a lot of photographs and film reports about the Tanztheater company. Dancers get on with the job in this place, which has neither clock nor windows (Figure 3), which makes it an out of time and private space. These two practical details were evoked by several dancers during interviews, but they showed up in the conversation only after talking about the notion of concentration. According to the dancers we interviewed, concentration often appears as one of the most representative aspects of the Lichtburg. A dancer of the company mentions the creative process and rehearsals in Wuppertal: “She [i.e. Pina Bausch] knew it was here her dancers would be working, [and] she was right.”2 According to her, the site of Wuppertal seems to have kept dancers away from distractions that are offered to them in the big cities they visit during their tours. This dimension may also be found in critical receptions of these works. The term “industrial” and the use of grey to talk about meteorological patterns fill the pages of newspapers outside Germany that cover Tanztheater’s events. The city of Wuppertal both pleases and displeases at the same time. Nevertheless, during the interviews, dancers did not just show the “periphery asset” (Barriendos 2009: 103) of the city, they introduce the Lichtburg as a very particular place that has a high emotional value for them. Most of the company’s dancers, like Bausch herself, give a particular emotional charge to the Lichtburg that seems to stimulate concentration and favor creation. In their speech, this emotional link legitimizes the permanent return to Wuppertal and more precisely to the Lichtburg, which is the main site of both creation and rehearsals. Even if a work begins abroad in the context of a collaboration with another theater, the main part of the creation takes place in the Lichtburg. The studio refers to a physical place, but also to an important symbol. It is both a physical and a symbolic space. Debarbieux sums up the complexity of the phrase haut lieu in this double status: physical and symbolic (Debarbieux 1993).

A rehearsal assistant stated: “The Lichtburg, it’s our story… Here there is a soul, I think, as soon as someone enters the room, not only for us, but also for anyone coming from the outside. I think there is something, all these lived years are here, there might be ghosts.”3 By saying this, the assistant and dancer is conveying the symbolic dimension of the place. Debarbieux’s observations confirm that the object of a symbolization can be explained by imagination. He writes: “Space does not speak but refers to a meaning we have given it, which we are able to feel in its presence” (Debarbieux 1993: 7; transl. Fournier). The Lichtburg is the place where dancers have sought, created and rehearsed since the beginning of the 1970s. Different generations of dancers have worked in this studio. The long term plays a part in the place’s mythical dimension. Its symbolic functioning is asserted by the gathering of dancers. One interviewed dancer said that all the company’s dancers live in Wuppertal, given the schedules.4 Wuppertal thus represents the place where the dancers work, live, and have to live, but beyond that, it is a symbol of a collective identity composed of members from very various cultures and of diverse “cultural identities” (Jullien 2016). By the phrase “collective identity”, we refer to “the feeling and will shared by several individuals that they belong to the same group” (Debarbieux 2006: 342; transl. Fournier). It is important to recall such a phenomenon given the many-sided aspects of Bausch’s company. In other companies across different countries, dancers are accustomed to a lifestyle that is perhaps less rooted a single city. They often navigate between multiple artistic projects, collaborating with various companies in different cities. In contrast, at Tanztheater Wuppertal, dancers from around the world come together to join the company, which necessitates relocating to Wuppertal and becoming a resident of the city. Season after season, the group of dancers has diversified itself more and more, recruiting other dancers from a variety of backgrounds, mother tongues and cultural affiliations in general. How could one regular place, the studio, have acquired a particular meaning for such a diversified social group? Through practices and affects, the group transformed the place by conferring on it a sacred dimension. Imageries composed of press articles, documentaries and photograph albums show dancers moving inside the Lichtburg studio, around the green walls of the room that became one of the most recognizable of dance studios. By being particularly attached to a local place that in appearance is common but certainly singular, the company has reversed the usual opposition between locality and globality and articulated a high degree of mobility with locality.

When dancers evoke the emotional charge in the Lichtburg, it is often linked to personal trajectories. Beyond the fact that this studio is filled with memories and inspirations from residencies abroad (co-productions), which have always nourished its dance creation, the Lichtburg represents an arrival point for some of the dancers themselves. It is important not to forget the political approach of these migrations in the arts because these enable the redefinition of migration narratives beyond national identities. This can be regarded as a direct social and aesthetic consequence of the mobility of dancers and the ensuing effects (Bench and Elswit 2016). This aspect is sometimes shown in the works and is even exploited aesthetically. One example of this link between migration and mobility is to be observed in the heart of Bausch’s works directly on stage. In Nelken (1982), a group of dancers pose like a ballerina. Each dancer is looking at the audience and is telling in a very few words why he or she has become a dancer. On stage in Avignon, one of them, originally from Prague, says in French with a distinct accent: “Je suis devenu danseur parce que je ai eu une accident, parce que je ne voulu pas être soldat (I have become a dancer because I had an accident, because I didn’t want to be a soldier)(Akerman 1983). Behind this scene, there is a whole range of possibilities that offers each dancer in the Lichtburg studio the opportunity to relate part of his or her story and experience of transnationalism. This point about migration demonstrates new expressions of selfhood, as well as old ones. These modes of expression travel across the world through different countries. This way of dancing also expresses a certain migrant transnationalism; mobilities are directly involved in dance when Bausch discovers other countries, cities, dancers from different countries and adds those cultural and artistic influences to her works. In a similar way, a Greek dancer in the ensemble recalls his experience in the 1990s. He travelled by train from Greece to Germany to be auditioned. When he arrived there was no audition, but he met Bausch, who advised him to go to Essen to study dance and to stay around for the next audition. In Greece, the young dancer would be forced to do military service for one year, which would be a loss for his dance education: “When I arrived here [Germany], I had a big problem with Greece. I couldn’t go back to Greece anymore because of military service. If I had gone back there, I would have been forced to do my military service, but I didn’t want to. At that time, military service lasted two years.” When he related his journey to Germany during the interview, the dancer insisted on the Lichtburg studio, as if this place symbolized an arrival point and at the same time a place to be anchored in. These two specific and isolated examples of dancers’ personal trajectories express what it is to be understood when interviewed dancers talk about the spirit of the space and their imaginary link to this studio. The Lichtburg appears as a shelter for creation for cosmopolitan dancers. In any case, we must take into account the emotional power associated with the place of creation and rehearsal. Narrating one’s own story in the studio or incorporating one’s migratory trajectory as dramaturgical material are elements of narrative and practice that bear witness to the distinctiveness of the site.

The Pina Bausch Foundation and Tanztheater Wuppertal: Two Local Chosen Sites for Translocal and Transnational Influences

In Wuppertal, some places are called after Bausch. The company’s name itself specifies the artistic genre, the site and the name: Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch. After Bausch’s passing, therefore, an eponymous foundation was created. These two institutions collected her choreography and the company’s archives. The conservation of her material memory led to archival exhibitions, publications and revivals of works from the repertoire. As decision-makers, the foundation and the company are two different institutions, but materialize in the form of an haut lieu by functioning as a hyper-structure and by being localized in Wuppertal. Moreover, the two local sites participate in materializing and symbolizing Wuppertal as an haut lieu of dance by aspiring to give the city an emblematic building which would stand out from the urban landscape. The long-term project of the two structures is to cooperate in a joint action: the creation of a Pina Bausch Center (Pina Bausch Zentrum). It would be a whole complex located in the city center where the current Schauspielhaus is. In the meantime, the Foundation has become recognizable in the public arena thanks to a logo composed of the four letters of Bausch’s forename, and it has its own office, separate from the Tanztheater Wuppertal’s office.

What kinds of influence do these institutions have, and on what is this influence based? The assembling of the archives appears to be the main response. They could have been scattered around the world in a multiplicity of places, but Wuppertal is the one fixed location in which a very diverse collection of archives is to be kept. This fixed place gathers together the company, rights, and material and immaterial archives of Tanztheater. A trip to United States, where Bausch received her dance education, was undertaken in order to bring some archives back to Wuppertal (Wagenbach, Pina Bausch Foundation 2014). This action of collecting traces of the works and making them accessible in one place gives the Pina Bausch Foundation and Tanztheater Wuppertal their influence. It appears important at this point to note that archives are searchable in situ and with an authorization request without any possibility of being reproduced. By gathering the archives in one fixed place, a central status to this hyper-structure is guaranteed, making it possible for it to exercise a power of influence, as well as attraction.

Power would also mean being able to influence other stages worldwide, especially young stages. For this reason, the Pina Bausch Foundation welcomes choreographers from different backgrounds and nationalities—who might follow a Bauschian tradition—in a very institutional way through fellowship programs. This influence is due to the close connection between the Wuppertalien stage and the international stage, an aspect that we can detect in the critical reception to the idea of presenting Bausch no longer as a German but as an artist who transcends the “enclosing nationalities” (Noisette 2007; transl. Fournier).

In this way, individual singularities within the company are interwoven with a collective body. Despite its increasingly international composition and global touring, the company, rooted in Wuppertal, has long continued to be perceived overwhelmingly as German. However, as the members traverse the world and the theme of “elsewhere” gains prominence in their works, the concept of diversity becomes more and more significant to both the audience and the critics. This overarching theme is in line with the company’s sociocultural realities, comprised of dancers with diverse backgrounds and resources. The role of diversity seems to have played a significant part in establishing Wuppertal as a prominent center, and it remains essential for the company’s place in a globalized artistic landscape.

Silhouettes, figures, dances, languages and nationalities form intricacies of diversity within the works. Consequently, the choreographer’s approach is aligned with an aesthetic of diversity, bridging the gap between dance and anthropology. The incorporation of a “salad of languages”5, mixing German with the various languages spoken within the ensemble, contributes to an aesthetic rooted in a “geographical discontinuity” (Aslan 1997; transl. Fournier). The presence of diverse nationalities generates an interesting semantic shift in the press: Bausch is no longer solely associated with German identity but, like her cosmopolitan company, acquires an international stature.

Bausch’s encounters with cultural otherness are not framed within a “methodological nationalism” but rather become the subject of a “mise en genre”, “a process that associates an aesthetic, a culture and a country” (Cicchelli, October 2018; transl. Fournier). Choreographic performances have the potential to transcend categorizations rooted in nationality. By decentering itself, the choreographic work does not aim to change the place of enunciation, which is visibly Germany, but rather to reevaluate certain principles and cultural codes in the light of encounters with different locales. The aim is indeed to decentralize in order to create and revisit knowledge such as standards of beauty and the constraints of classical ballet, for instance. While some journalists may reduce dance to simplistic national labels, Tanztheater Wuppertal is gradually becoming a manifestation of a “new internationalism” (Quirós and Imhoff 2014:13; transl. Fournier) that intertwines multiple scales and diverse geographical and imaginative regions.

Theaters: Collective Memory Spaces Beyond the Enclosing Nationalities

By taking the example of Wuppertal, we can link the notion of the haut lieu with others, such as the cosmopolitan aspect of the company that we explored earlier, but also notably with a “memory space” (“lieu de mémoire,” Nora 1984). Assaf Dahdah, a geographer, points out the epistemological link between the haut lieu and Pierre Nora’s lieux de mémoire. Dahdah quotes Debarbieux (1995) when he claims that space and time are two inseparable dimensions: “because it expresses a collective need of positioning between the past, the present and the future, territory is shaped by memory” (Dahdah 2015; transl. Fournier). Wuppertal is also the place where the different times of the œuvre’s life are articulated; for example, from 1983 Bausch began to present re-creations (Neueinstudierungen) of her works. In 1987 the first retrospective of her work (around twenty works at that time) was held. Whereas the company started to create works abroad (cooperating with Italy in 1986), Bausch was beginning to develop in parallel the steps of a reterritorialization of her work and, more than that, she made Wuppertal the place where the work would develop its own internal system of references by updating it with re-creations, retrospectives, and festivals. Past time corresponds to the re-creations and presentations of the repertoire, present time refers to the creation locally and the premieres, and future time coincides with processes of transmission. Wuppertal responds to a collective need to articulate the œuvre’s different eras spatially: the past, the present and the future. Gathering archives in one place then means reconciling these three time-frames, which also goes along with legitimacy and responsibility for the life of the œuvre.

If the hyper-structure we mentioned earlier has that much influence, it is only because the sacred dimension of the works and the system of territorial values requires to be kept locally. We think here of the works themselves. We now have to explain how the company’s works in theaters all over the world have been seen as particular and even sacred. Since the middle of the 1990s, the Tanztheater’s works have clearly been making a statement in the dance world and earning their reputation according to the press and critical reception. This is obviously partially due to the iconic dancers, who have been part of the company since the very beginning. In the press, descriptions conferring on the dancers a sacred dimension became much more prevalent. The dancers would have become “guardians of memory” (“gardiens de la mémoire,” Solis 1995:35) according to the press. When Bandoneon (1980), a work from the repertoire, was played in the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris in 2007, it was called a “revival” (Verrièle 2007). The event was announced with a reference to its story: “the choreographer never forgot to preserve large masterpieces [monuments in French] that made her renowned” (Anon 2007: 53). Bandoneon, the play, is qualified as “monumental” (Anon 2007: 53) and as a “performance myth” (Verrièle 2007). A few years before, in 2001, when Wiesenland was presented in Paris, a journalist mentioned the sacred value given to the work and the collective identification with Tanztheater’s dancers: “With Pina Bausch, the Théâtre de la Ville is no longer a place of performance, but a place of worship. We await this annual event and get ready for it. It is a ritual, even better, a big family celebration […] we love those dancers as cousins from Wuppertal […] they are more than familiar […]” (Sirvin 2001; transl. Fournier).

After Pina Bausch’s passing in 2009, her renown was assured worldwide and her work was repeatedly updated through a series of creations that are the homage-creations of dancers, through the transmission of Bausch’s roles in Café Müller (1978) and Danzón (1995), and their incarnations, the two versions of Kontakthof, or through the reconstruction of the repertoire’s works in other dance hauts lieux: l’Opéra de Paris for Sacre, or by other choreographers like Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui for Café Müller, for example. In all these cases, the reference to the place of Wuppertal is a recurring question, central to the works and the contexts of their presentation. The return to Wuppertal, to the sources, to the roots where dance and works are rehearsed, has a role in the construction of the haut lieu and participates in its legitimacy. These references gather together a community composed of members from various national backgrounds and strengthen it. Hence the œuvre takes root in Wuppertal, whereas the context of its renown is worldwide. The identification and symbolization processes of an haut lieu are intrinsically collective. If the works appear as a monument, it is as a collective monument.

Conclusion

Wuppertal can be considered an haut lieu of dance because it refers to a real and located place. The symbolic dimension of Wuppertal, the emotional charge conferred on the Lichtburg studio, the influences of two local institutions, and finally the theaters where the company’s members are seen as “cousins from Wuppertal” contribute to explaining how Wuppertal has become an haut lieu of dance. Initially in this article, we have seen that the centrality of Wuppertal is given by the dancers’ high mobility abroad, as well as by the human flows generated by audiences and dancers. The second point considered the emotional charge given to the Lichtburg regarding the migration trajectories of the dancers, while the third discussed the translocal and transnational influences of local institutions. Finally, in order to understand theaters as memory spaces, it was found necessary to consider the transformation of dancers from various national backgrounds into “cousins from Wuppertal” as a factor.

All of these observations are linked to the notion of diversity and the fact that the company is composed of cosmopolitan members. Does this place change our way of seeing and classifying space? The relation to notoriety here escapes the centralism that is usually confined to world dance capitals in a context of globalization and makes visible an asymmetrical phenomenon that persists. The œuvre, through its circulation, has experienced a growing notoriety. Wuppertal has become an haut lieu because it has a highly symbolic dimension: it focuses power and is collectively identified. This haut lieu is fixed and located, and the œuvre returns constantly to its place of birth after acquiring renown worldwide. What is particularly noteworthy is not so much the centrality of Wuppertal itself: it was mentioned earlier that it is neither isolated nor exceptional within the political framework of a federal government like Germany’s. Instead, the focus is on how its symbolic power becomes evident. This can only be understood by examining the dynamics of the company’s circulation. Spatial strategies come into play, involving tours, key locations, and constant movement between major artistic hubs and Wuppertal itself. Additionally, the symbolic dimension is intertwined with the personal migratory trajectories of the dancers, which are central to Bauschian artistic creation. Furthermore, there is the iconic project that encompasses a strong effort at institutionalization, aiming to repatriate the archives and traces of the company to the local site, thereby enhancing the symbolic nature of Wuppertal on the mental map of dance. Lastly, there is the transcendental dimension of the performances, which seeks to surpass the boundaries imposed by nationalities.

This final aspect highlights how, within the works themselves, a shift occurs, with the company embodying a narrative driven by personal and collective migrations while being presented in a highly specific theater.

Note on the Author

Marion Fournier holds a PhD in aesthetics from the University of Lorraine . Her research aims to contribute to a geoaesthetics of reception. Combining cultural historical and geographical approaches, she analyses the influence of diverse spatial factors on dance aesthetics and more precisely on the aesthetics of reception. Having been supported by a long-term DAAD research scholarship in Wuppertal, she examines Pina Bausch Tanztheater’s notoriety and artistic recognition through the circulation of the company and its works both nationally and globally. She discusses mobility’s positive assets and the way it leads to representations of diversity in Pina Bausch works both on stage and in their critical reception.

Email: marion-fournier@hotmail.com

References

Akerman, C. 1983. Un jour, Pina a demandé. INA. 57 min.

Anon. 2007. Pina Bausch d’hier et d’aujourd’hui. Mixte, June. In: Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, Pressearchiv, Bandoneon 1, S1 027.

Apprill, C. 2015. One step beyond. La danse ne circule pas comme la musique. Géographies et cultures 96: 131-150. https://doi.org/10.4000/gc.4236.

Aslan, O. 1997. Danse/Théâtre. Pina Bausch I et II. Théâtre/Public, N°138, N°139.

Barriendos, J. 2009. “Geopolitics of Global Art. The Reinvention of Latin America as a Geoaesthetic Region.” In The Global Art World. Audiences, Markets and Museums, edited by B. Belting and A. Buddensieg. Ostfildern: Hatje-Cantz.

Barriendos, J. 2014. “Un cosmopolitisme esthétique? De “l’effet Magiciens” et d’autres antinomies de l’hospitalité artistique globale.” In Géoesthétique, edited by K. Quirós and A. Imhoff Paris: éditions B42.

Bench, H. and Elswit, K. 2016. Mapping Movement on the Move: Dance Touring and Digital Methods. Theatre Journal 68 (4), Johns Hopkins University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/645397 (Accessed 15 December 2023).

Besse, J.M. 2010. Approches spatiales dans l’histoire des sciences et des arts. L’Espace géographique 339): 211-224. https://doi.org/ 10.3917/eg.393.0211

Cicchelli, V. and Octobre, S. 2018. Cosmopolitisme esthético-culturel. Publictionnaire. Dictionnaire encyclopédique et critique des publics. https://publictionnaire.huma-num.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/cosmopolitisme-esthetico-culturel.pdf (Accessed 15 December 2023).

Clerc, P. 2004. “Haut lieu.” Hypergéo. https://hypergeo.eu/haut-lieu/ (Accessed 15 December 2023).

Dahdah, A. 2015. “Du Spatial turn au tournant spatial géographique. Une brève introduction.” TELEMMe. https://jjctelemme.hypotheses.org/740 (Accessed 15 December 2023).

Debarbieux, B. 1993. Du haut lieu en général et du mont Blanc en particulier. L’Espace géographique 1: 5-13.

Debarbieux, B. 1995. Le lieu, le territoire et trois figures de rhétorique. L’Espace géographique 2: 97-112.

Debarbieux, B. 2006. Prendre position: Réflexions sur les ressources et les limites de la notion d’identité en géographie. L’Espagne géographique 35(4): 340-354. https://doi.org/ 10.3917/eg.354.0340

Georget, J.L. and Robin, G. 2017. Introduction. La danse contemporaine dans l’espace germanique. Allemagne d’aujourd’hui 220(2): 67-71. https://doi.org/10.3917/all.220.0067

Gonçalves, S. 2019. Le Boléro comme “lieu de mémoire”. Recherches en danse 7. https://doi.org/ 10.4000/danse.2432

Huesca, R. 2010. L’écriture du (spectacle) vivant. Strasbourg: Le portique.

Jauss, H.R. 1978. Pour une esthétique de la réception. Paris: Gallimard.

Jullien, F. 2016. Il n’y a pas d’identité culturelle. Paris: L’Herne.

Meyer, M. 2016. Pina Bausch. Tanz kann fast alles sein. Remscheid: Bergisches Verlag.

Noisette, P. 2007. Zoom. Pina Bausch. Danser n° 266: 53.

Nora, P. 1984. Les lieux de mémoire, Paris: Gallimard.

Paquot, T. 2011. L’Avenir des villes. Paris: Les Carnets des Dialogues du Matin, Institut Diderot.

Piotrowski, P. 2014. “Du tournant spatial ou une histoire horizontale de l’art.” In Géoesthétique, edited by K. Quirós and A. Imhoff. Paris: éditions B42.

Quirós, K. and Imhoff, A. 2014. “Glissements de terrain.” In Géoesthétique, edited by K. Quirós and A. Imhoff. Paris: éditions B42

Sassen, S. 2002. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sirvin, R. 2001. Pina Bausch, toute séduction dehors. Le Figaro, 9 and 10th June. In: Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, Pressearchiv, Wiesenland Ein Stück von Pina Bausch 1, S2 0 62.

Solis, R. 1995. “Bausch, un triste jeu de deuil.” Libération, February 13, 1995. https://www.liberation.fr/culture/1995/02/13/pina-bausch-un-triste-jeu-de-deuil-trauerspiel-jeu-de-deuil_123644/

Verrièle, P. 2007. Bandoneon revival. 20 Minutes, 5th June. In: Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, Pressearchiv, Bandoneon 1, S1 027.

Wagenbach, M. and Pina Bausch Foundation. 2014. Tanz erben. Pina lädt ein. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Wenders, W. 2009. Pina. Tanzt, tanzt, sonst sind wir verloren. 106min.

Wenders, W. 2010. “Consoler les œillets? Peter Pabst converse avec Wim Wenders.“ In Peter pour Pina, edited by Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch GmbH. Dortmund: Kettler.

- The interviews quoted in the text were conducted in French and German and have been translated by the author.

- Interview with Clémentine Deluy. 22nd February 2017 in Wuppertal.

- Interview with Bénédicte Billiet. 26th May 2017 in Wuppertal.

- Interview with Clémentine Deluy. 22nd February 2017 in Wuppertal.

- Interview with Daphnis Kokkinos. 10th October 2017 in Wuppertal.